#WITMonth, Part I: Susanna Bissoli, Jente Posthuma and More

I’m starting off my Women in Translation month coverage with two short novels: one Italian and one Dutch; both about women navigating loss, family relationships, physical or mental illness, and the desire to be a writer.

Struck by Susanna Bissoli (2024; 2025)

[Translated from Italian by Georgia Wall]

Vera has been diagnosed a second time with breast cancer – the same disease that felled her mother a decade ago. “I’m fed up with feeling like a problem to be taken care of,” she thinks. Even as her treatment continues, she determines to find routes to a bigger life not defined by her illness. Writing is the solution. When she moves in with her grouchy octogenarian father, Zeno Benin, she discovers he’s secretly written a novel, A Lucky Man. The almost entirely unpunctuated document is handwritten across 51 notebooks Vera undertakes to type up and edit alongside her father as his health declines.

At the same time, she becomes possessed by the legend of local living ‘saint’ Annamaria Bigani, who has been visited multiple times by the Virgin Mary and learned her date of death. Wondering if there is a story here that she needs to tell, Vera interviews Bigani, then escapes to Greece for time and creative space. “Do they save us, stories? Or is it our job to save them? I believe writing that story, day in and day out for years, saved my father’s life. But I’m sorry, I don’t have time to save his story: I need to write my own. The saint, or so I thought.” In the end, we learn, Struck – the very novel we are reading – is Vera’s book.

The title comes from a scientific study conducted on people struck by lightning at a country festival in France. How did they survive, and what were the lasting effects? The same questions apply to Vera, who avoids talking about her cancer but whose relationship with her sister Nora is still affected by choices made while their mother was alive. There are many delightful small conversations and incidents here, often involving Vera’s niece Alice. Vera’s relationship with Franco, a doctor who works with asylum seekers, is a steady part of the background. A translator’s afterword helped me understand the thought that went into how to reproduce Vera and others’ use of dialect (La Bassa Veronese vs. standard Italian) through English vernacular – so Vera and her sister say “Mam” and her father uses colourful idioms.

Though I know nothing of Bissoli’s biography, this second novel has the feeling of autofiction. Despite its wrenching themes of illness and the inevitability of death, it’s a lighthearted family story with free-flowing prose that I can enthusiastically recommend to readers of Elizabeth Berg and Catherine Newman.

This was my introduction to new (est. 2023) independent publisher Linden Editions, which primarily publishes literature in translation. I have two more of their books underway for another WIT Month post later this month. And a nice connection is that I corresponded with translator Georgia Wall when she was the publishing manager for The Emma Press.

With thanks to Linden Editions for the free copy for review.

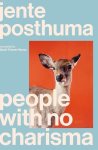

People with No Charisma by Jente Posthuma (2016; 2025)

[Translated from Dutch by Sarah Timmer Harvey]

Dutch writer Jente Posthuma’s quirky, bittersweet first novel traces the ripples that grief and mental ill health send through a young woman’s life. The narrator’s mother was an aspiring actress; her father runs a mental hospital. A dozen episodic short chapters present snapshots from a neurotic existence as she grows from a child to a thirtysomething starting a family of her own. Some highlights include her moving to Paris to write a novel, and her father – a terrible driver – taking her on a road trip through France. Despite the deadpan humor, there’s heartfelt emotion here and the prose and incidents are idiosyncratic. (Full review forthcoming for Shelf Awareness)

Dutch writer Jente Posthuma’s quirky, bittersweet first novel traces the ripples that grief and mental ill health send through a young woman’s life. The narrator’s mother was an aspiring actress; her father runs a mental hospital. A dozen episodic short chapters present snapshots from a neurotic existence as she grows from a child to a thirtysomething starting a family of her own. Some highlights include her moving to Paris to write a novel, and her father – a terrible driver – taking her on a road trip through France. Despite the deadpan humor, there’s heartfelt emotion here and the prose and incidents are idiosyncratic. (Full review forthcoming for Shelf Awareness)

& Reviewed for Foreword Reviews a couple of years ago:

What I Don’t Want to Talk About by Jente Posthuma (2020; 2023)

[Translated from Dutch by Sarah Timmer Harvey]

A young woman bereft after her twin brother’s suicide searches for the seeds of his mental illness. The past resurges, alternating with the present in the book’s few-page vignettes. Their father leaving when they were 11 was a significant early trauma. Her brother came out at 16, but she’d intuited his sexuality when they were eight. With no speech marks, conversations blend into cogitation and memories here. A wry tone tempers the bleakness. (Shortlisted for the European Union Prize for Literature and the International Booker Prize.)

A young woman bereft after her twin brother’s suicide searches for the seeds of his mental illness. The past resurges, alternating with the present in the book’s few-page vignettes. Their father leaving when they were 11 was a significant early trauma. Her brother came out at 16, but she’d intuited his sexuality when they were eight. With no speech marks, conversations blend into cogitation and memories here. A wry tone tempers the bleakness. (Shortlisted for the European Union Prize for Literature and the International Booker Prize.)

Both featured an unnamed narrator and a similar sense of humor. I concluded that Posthuma excels at exploring family dynamics and the aftermath of bereavement.

I got caught out when I reviewed The Appointment, too: Volckmer doesn’t technically count towards this challenge because she writes in English (and lives in London), but as she’s German, I’m adding in a teaser of my review as a bonus. Oddly, this novella did first appear in another language, French, in 2024, under the title Wonderf*ck. [The full title below was given to the UK edition.]

Calls May Be Recorded [for Training and Monitoring Purposes] by Katharina Volckmer (2025)

Volckmer’s outrageous, uproarious second novel features a sex-obsessed call center employee who negotiates body and mommy issues alongside customer complaints. “Thank you for waiting. My name is Jimmie. How can I help you today?” each call opens. The overweight, homosexual former actor still lives with his mother. His customers’ situations are bizarre and his replies wildly inappropriate; it’s only a matter of time until he faces disciplinary action. As in her debut, Volckmer fearlessly probes the psychological origins of gender dysphoria and sexual behavior. Think of it as an X-rated version of The Office. (Full review forthcoming for Shelf Awareness)

Volckmer’s outrageous, uproarious second novel features a sex-obsessed call center employee who negotiates body and mommy issues alongside customer complaints. “Thank you for waiting. My name is Jimmie. How can I help you today?” each call opens. The overweight, homosexual former actor still lives with his mother. His customers’ situations are bizarre and his replies wildly inappropriate; it’s only a matter of time until he faces disciplinary action. As in her debut, Volckmer fearlessly probes the psychological origins of gender dysphoria and sexual behavior. Think of it as an X-rated version of The Office. (Full review forthcoming for Shelf Awareness)

20 Books of Summer, 9–10: Leave the World Behind & Leaving Atlanta

Halfway there! And I’m doing better than it might appear in that I’m in the middle of another 7 books and just have to decide what the final 3 will be. This was a sobering but satisfying pair of novels in which race and class play a part but the characters are ultimately helpless in the face of disasters and violence. Both: ![]()

Leave the World Behind by Rumaan Alam (2020)

The title heralds a perfect holiday read, right? A New York City couple, Amanda and Clay, have rented a secluded vacation home in Long Island with their teenagers, Archie and Rose, and plan on a week of great beach weather and mild hedonism: food, drink, secret cigarettes, a hot tub, maybe some sex. But late on the first night there’s a knock on the door from the owners, sixtysomething Black couple Ruth and G. H. Something is going on; although the house still has power, all phone and Internet services have gone down. Rather than return to a potentially chaotic city, the older couple set course for their country retreat to hunker down. George is in finance and believes money solves everything, so he offers Amanda and Clay $1000 cash for the inconvenience of having their holiday interrupted.

From an amassing herd of deer to Archie’s sudden mystery illness, everything quickly turns odd. Glimpses of what’s happening in the wider world are surrounded by a menacing haziness, but the events seem to embody modern anxieties about being cut off from information and wondering who to trust. Given the blurbs and initial foreshadowing, I expected racial tension to be a main driver of an incendiary household climax. Instead, the threat is external and largely unexplained, and the couples are forced to rely on each other as tribalism sets in. (It’s uncanny that this was written before Covid, published during.)

From an amassing herd of deer to Archie’s sudden mystery illness, everything quickly turns odd. Glimpses of what’s happening in the wider world are surrounded by a menacing haziness, but the events seem to embody modern anxieties about being cut off from information and wondering who to trust. Given the blurbs and initial foreshadowing, I expected racial tension to be a main driver of an incendiary household climax. Instead, the threat is external and largely unexplained, and the couples are forced to rely on each other as tribalism sets in. (It’s uncanny that this was written before Covid, published during.)

This was a book club read and one of the most divisive I can remember. I was among the few who thought it gripping, intriguing, and even genuinely frightening. Others found the characters unlikable, the plot implausible or silly, and the writing heavy-handed. Alam is definitely poking fun at privileged bougie families. He draws attention to the author as puppet-master, inserting shrewd hints of what is occurring elsewhere or will soon befall certain characters. Some passages skirt pomposity with their anaphora and rhetorical questioning. Alliteration, repetition, and stark pronouncements make the prose almost baroque in places. Alam’s style is theatrical, even arch, but it suits the premonitory tone. I admired how he constantly upends genre expectations, moving from literary fiction to domestic drama to dystopia to magic realism to horror. The stuff of nightmares – being naked in front of strangers, one’s teeth falling out – becomes real, or at least real in the world of the book. The reminder is that we are never as in control as we think we are; always, disasters are unfolding. What will we do, and who will we be, as the inevitable unfolds?

You demanded answers, but the universe refused. Comfort and safety were just an illusion. Money meant nothing. All that meant anything was this—people, in the same place, together. This was what was left to them.

Absorbing, timely, controversial: read it! (Free from a neighbour)

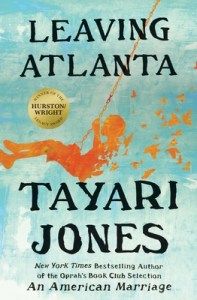

Leaving Atlanta by Tayari Jones (2002)

Jones’s debut novel is about the Atlanta Child Murders, a real-life serial killer spree that targeted 29 African American children between 1979 and 1982. (Two of the victims attended her elementary school.) Rather than addressing the gruesome reality, however, she takes a sideways look by considering the effect that fear has on students whose classmates start disappearing. Three sections rather like linked novellas take on the perspective of three different Oglethorpe Elementary fifth graders: LaTasha Baxter, Rodney Green, and Octavia Harrison. The POV moves from third to second to first person, a creative writing experiment that succeeds at pulling readers closer in. The AAVE-inflected dialogue and interactions feel genuine in each, and I liked the playful addition of “Tayari Jones” as a fringe character.

Jones’s debut novel is about the Atlanta Child Murders, a real-life serial killer spree that targeted 29 African American children between 1979 and 1982. (Two of the victims attended her elementary school.) Rather than addressing the gruesome reality, however, she takes a sideways look by considering the effect that fear has on students whose classmates start disappearing. Three sections rather like linked novellas take on the perspective of three different Oglethorpe Elementary fifth graders: LaTasha Baxter, Rodney Green, and Octavia Harrison. The POV moves from third to second to first person, a creative writing experiment that succeeds at pulling readers closer in. The AAVE-inflected dialogue and interactions feel genuine in each, and I liked the playful addition of “Tayari Jones” as a fringe character.

Even as their school is making news headlines, the children’s concerns are perennial adolescent ones: how to avoid bullying, who to sit with at lunch, how to be friendly yet not falsely encourage members of the opposite sex. And at home, all three struggle with an absent or overbearing father. At age 11, these kids are just starting to realize that their parents aren’t perfect and might not be able to keep them safe. I especially warmed to Octavia’s voice, even as her story made my heart ache: “cussing at myself for being too stupid to see that nothing lasts. That people get away from you like a handful of sweet smoke.” I preferred this offbeat, tender coming-of-age novel to Silver Sparrow and would place it on a par with An American Marriage. (Birthday gift from my wish list)

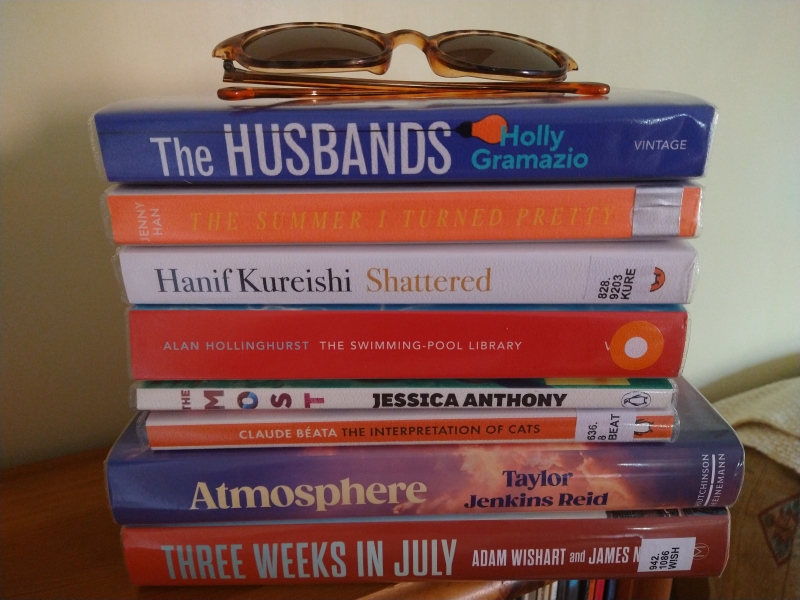

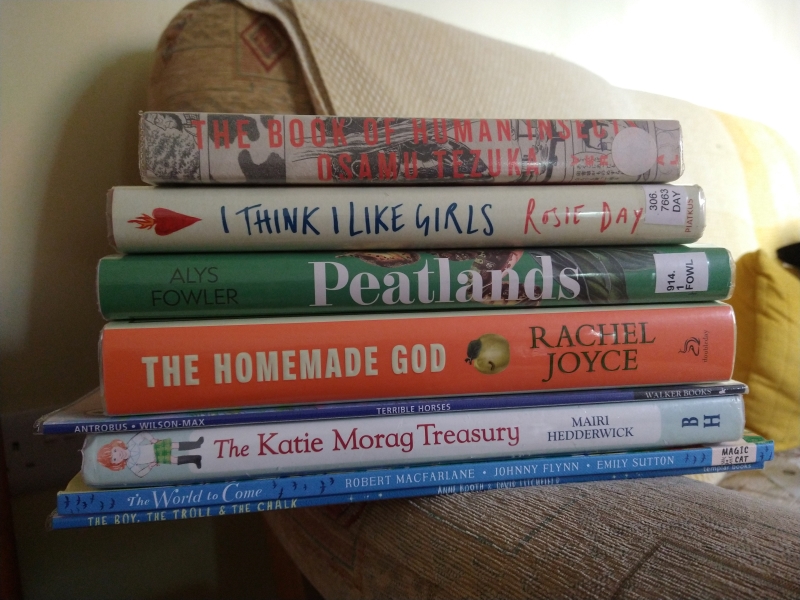

Love Your Library, July 2025

Thank you to Eleanor (here and here) and Skai for posting about their recent library reading.

On a brief trip to Tilehurst last week for a podiatry consultation, I popped into its library (part of Reading Borough, where I’ve lived at various points) and liked how they designated subgenres with 3D paper letter names above the bays along with a suitable spine sticker on the books themselves. Action is to the right of romance here; they also give Family Sagas and Historical Fiction their own sections.

My library system recently made a slight change to our classifications. Now, instead of a monolithic Crime designation (red circular sticker on spine) there will be a white square spine label with either a magnifying glass and CRI or a gun target with THR for thriller; both will be shelved in the Crime section. Likewise, the SFF section (previously, green circular sticker) will have two subdivisions, FAN with a unicorn and SCI with a ringed planet. I can see why the new subgenres were perceived to be more helpful for readers, but I predict that the shelving, which is almost exclusively done by volunteers, will go haywire. Even with the very clear coloured stickers, books are frequently mis-shelved. (During each of my sessions, I probably reshelve 10 to 15 books.) Now there will be a mixture of coloured and white labels, the latter of which must be read carefully to not end up on the wrong trolley or shelf…

My library use over the last month:

(links are to books not already reviewed on the blog)

READ

- Don’t Forget We’re Here Forever: A New Generation’s Search for Religion by Lamorna Ash

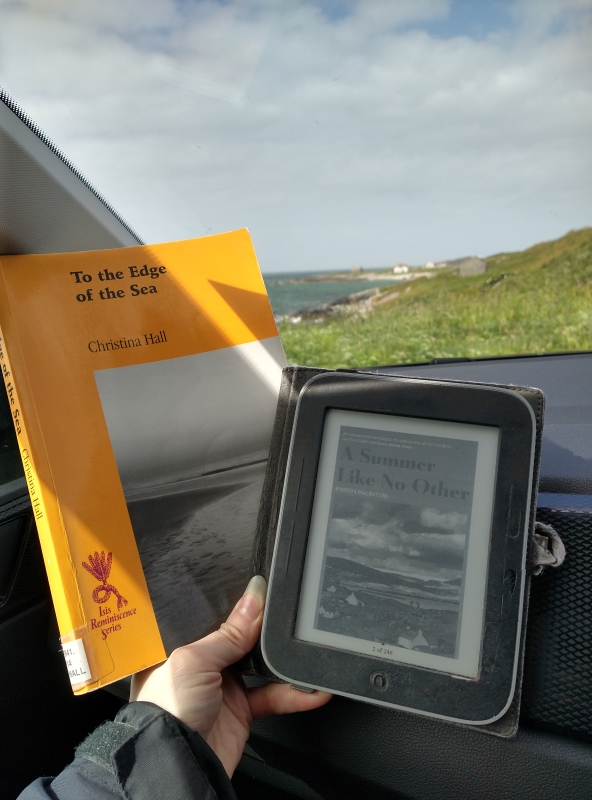

- To the Edge of the Sea: Schooldays of a Crofter’s Child by Christina Hall

- Shattered by Hanif Kureishi

- Ripeness by Sarah Moss

- Three Weeks in July: 7/7, The Aftermath, and the Deadly Manhunt by Adam Wishart & James Nally

CURRENTLY READING

- The Most by Jessica Anthony

- The Interpretation of Cats: And Their Owners by Claude Béata; translated by David Watson

- The Honesty Box by Luzy Brazier

- Bellies by Nicola Dinan

- The Homemade God by Rachel Joyce

- The Mermaid Chair by Sue Monk Kidd

- The Secret Lives of Booksellers and Librarians: True Stories of the Magic of Reading by James Patterson & Matt Eversmann

CHECKED OUT, TO BE READ

- I Think I Like Girls by Rosie Day

- Fragile Minds by Bella Jackson

- Enchanted Ground: Growing Roots in a Broken World by Steven Lovatt

- Wife by Charlotte Mendelson

- The Forgotten Sense: The Nose and the Perception of Smell by Jonas Olofsson

+ various children’s books

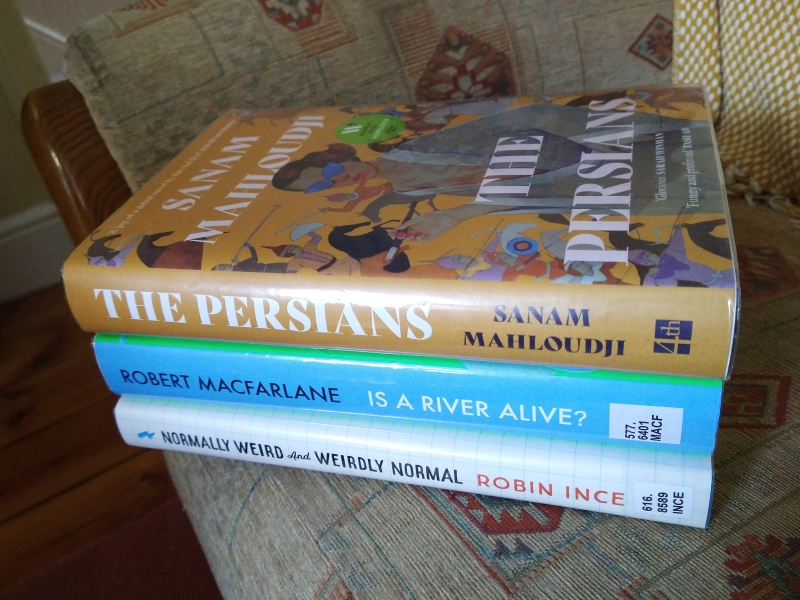

(the other books pictured are for my husband’s stack)

IN THE RESERVATION QUEUE

- Helm by Sarah Hall

- An Eye on the Hebrides by Mairi Hedderwick

- Albion by Anna Hope

- The Names by Florence Knapp

- The Eights by Joanna Miller

- The Dig by John Preston

- Birding by Rose Ruane

- Opt Out by Carolina Setterwall

RETURNED UNFINISHED

- The Husbands by Holly Gramazio – I read the first 28 pages or so. A fun premise, but I felt I’d gotten the gist already and couldn’t imagine another 300 pages of the same.

- The Summer I Turned Pretty by Jenny Han – This was requested off me before I could get halfway. So annoying! I’ve placed a hold but don’t know if it will come back into my hands in time to actually finish it during the summer. Harrumph.

- Atmosphere by Taylor Jenkins Reid – I read about 18 pages. I always like the idea of her novels, but since Daisy Jones haven’t gotten far in one.

- Boiled Owls by Azad Ashim Sharma – This poetry collection was not for me.

RETURNED UNREAD

- Fulfillment by Lee Cole – Requested off me before I could start it. I’m back in the queue.

- Adam by Gboyega Odubanjo – This poetry collection was not for me.

- The Artist by Lucy Steeds – Requested off me before I could start it. I’m back in the queue.

- The Sleepwalkers by Scarlett Thomas – Ditto!

What have you been reading or reviewing from the library recently?

Share a link to your own post in the comments. Feel free to use the above image. The hashtag is #LoveYourLibrary.

Three Days in June vs. Three Weeks in July

Two very good 2025 releases that I read from the library. While they could hardly be more different in tone and particulars, I couldn’t resist linking them via their titles.

Three Days in June by Anne Tyler

(From my Most Anticipated list.) A delightful little book that I loved more than I expected to, for several reasons: the effective use of a wedding weekend as a way of examining what goes wrong in marriages and what we choose to live with versus what we can’t forgive; Gail’s first-person narration, a rarity for Tyler* and a decision that adds depth to what might otherwise have been a two-dimensional depiction of a woman whose people skills leave something to be desired; and the unexpected presence of a cat who brings warmth and caprice back into her home. (I read this soon after losing my old cat, and it was comforting to be reminded that cats and their funny ways are the same the world over.)

From Tyler’s oeuvre, this reminded me most of The Amateur Marriage and has a surprise Larry’s Party-esque ending. The discussion of the outmoded practice of tapping one’s watch is a neat tie-in to her recurring theme of the nature of time. And through the lunch out at a chic crab restaurant, she succeeds at making the Baltimore setting essential rather than incidental, more so than in much of her other work.

Gail is in the sandwich generation with a daughter just married and an old mother who’s just about independent. I appreciated that she’s 61 and contemplating retirement, but still feels as if she hasn’t a clue: “What was I supposed to do with the rest of my life? I’m too young for this, I thought. Not too old, as you might expect, but too young, too inept, too uninformed. How come there weren’t any grownups around? Why did everyone just assume I knew what I was doing?”

My only misgiving is that Tyler doesn’t quite get it right about the younger generation: women who are in their early thirties in 2023 (so born about 1990) wouldn’t be called Debbie and Bitsy. To some degree, Tyler’s still stuck back in the 1970s, but her observations about married couples and family dynamics are as shrewd as ever. Especially because of the novella length, I can recommend this to readers wanting to try Tyler for the first time. ![]()

*I’ve noted it in Earthly Possessions. Anywhere else?

Three Weeks in July: 7/7, The Aftermath, and the Deadly Manhunt by Adam Wishart and James Nally

July 7th is my wedding anniversary but before that, and ever since, it’s been known as the date of the UK’s worst terrorist attack, a sort of lesser 9/11 – and while reading this I felt the same way that I’ve felt reading books about 9/11: a sort of awed horror. Suicide bombers who were born in the UK but radicalized on trips to Islamic training camps in Pakistan set off explosions on three Underground trains and one London bus. I didn’t think my memories of 7/7 were strong, yet some names were incredibly familiar to me (chiefly Mohammad Sidique Khan, the leader of the attacks; Jean Charles de Menezes, the innocent Brazilian electrician shot dead on a Tube train when confused with a suspect in the 21/7 copycat plot – police were operating under a new shoot-to-kill policy and this was the tragic result).

Fifty-two people were killed that day, ranging in age from 20 to 60; 20 were not UK citizens, hailing from everywhere from Grenada to Mauritius. But a total of 770 people were injured. I found the authors’ recreation of events very gripping, though do be warned that there is a lot of gruesome medical and forensic detail about fatalities and injuries. They humanize the scale of events and make things personal by focusing on four individuals who were injured, even losing multiple limbs in some cases, but survived and now work in motivational speaking, disability services or survivor advocacy.

Fifty-two people were killed that day, ranging in age from 20 to 60; 20 were not UK citizens, hailing from everywhere from Grenada to Mauritius. But a total of 770 people were injured. I found the authors’ recreation of events very gripping, though do be warned that there is a lot of gruesome medical and forensic detail about fatalities and injuries. They humanize the scale of events and make things personal by focusing on four individuals who were injured, even losing multiple limbs in some cases, but survived and now work in motivational speaking, disability services or survivor advocacy.

What really got to me was thinking about all the hundreds of people who, 20 years on, still live with permanent pain, disability or grief because of the randomness of them or their loved ones getting caught up in a few misguided zealots’ plot. One detail that particularly struck me: with the Tube tunnels closed off at both ends while searchers recovered bodies, the temperature rose to 50 degrees C (122 degrees F), only exacerbating the stench. The book mostly avoids cliches and overwriting, though I did find myself skimming in places. It is based on the research done for a BBC documentary series and synthesizes a lot of material in an engaging way that does justice to the victims. ![]()

Have you read one or both of these?

Could you see yourself picking one of them up?

The Single Hound by May Sarton (1938)

I spotted that the 30th anniversary of May Sarton’s death was coming up, so decided to read an unread book of hers from my shelves in time to mark the occasion. Today’s the day: she died on July 16, 1995 in York, Maine. Marcie of Buried in Print joined me for a buddy read (her review). I was drawn by the title, which comes from an Emily Dickinson quote. It’s the ninth Sarton novel I’ve read and, while in general I find her nonfiction more memorable than her fiction, this impressionistic debut novel was a solid read. It was clearly inspired by Virginia Woolf’s work and based on Sarton’s memories of her time on the fringes of the Bloomsbury Group.

In Part I we are introduced to “the Little Owls,” three dear friends and winsome spinsters in their sixties – Doro, Annette and Claire – who teach and live above their schoolroom in Ghent, Belgium. (I couldn’t help but think of the Brontë sisters’ time in Belgium.) Doro, a poet, seems likely to be a stand-in for the author. I loved the gentle pace of this section; although the novel was published when she was only 26, Sarton was already displaying insight into friendship and ageing and appreciation of life’s small pleasures, elements that would recur in her later autobiographical work.

In Part I we are introduced to “the Little Owls,” three dear friends and winsome spinsters in their sixties – Doro, Annette and Claire – who teach and live above their schoolroom in Ghent, Belgium. (I couldn’t help but think of the Brontë sisters’ time in Belgium.) Doro, a poet, seems likely to be a stand-in for the author. I loved the gentle pace of this section; although the novel was published when she was only 26, Sarton was already displaying insight into friendship and ageing and appreciation of life’s small pleasures, elements that would recur in her later autobiographical work.

the three together made a complete world.

Was this life? This slow penetration of experience until nothing had been left untasted, unexplored, unused — until the whole of one’s life became a fabric, a tapestry with a pattern? She could not see the pattern yet.

tea was opium to them both, the time when the past became a soft pleasant country of the imagination, lost its bitterness, ceased to devour, and in some tea-inspired way nourished them.

Part II felt to me like a strange swerve into the story of Mark Taylor, an aspiring English writer who falls in love with a married painter named Georgia Manning. Their flirtation, as soon through the eyes of a young romantic like Mark, is monolithic, earth-shattering, but to readers is more of a clichéd subplot. In the meantime, Mark sticks to his vow of going on a pilgrimage to Belgium to meet Jean Latour, the poet whose work first inspired him. Part III brings the two strands together in an unexpected way, as Mark gains clarity about his hero and his potential future with Georgia, though cleverer readers than I may have been able to predict it – especially if they heeded the Brontë connection.

It was rewarding to spot the seeds of future Sarton themes here, such as discovering the vocation of teaching (The Small Room) and young people meeting their elder role models and soliciting words of wisdom on how to live (Mrs. Stevens Hears the Mermaids Singing). Through Doro, Sarton also expresses trust in poetry’s serendipitous power. “This is why one is a poet, so that some day, sooner or later, one can say the right thing to the right person at the right time.” I enjoyed my time with the Little Owls but mostly viewed this as a dress rehearsal for later, more mature work. (Secondhand – Awesomebooks.com) ![]()

Most Anticipated Books of the Second Half of 2025

My “Most Anticipated” designation sometimes seems like a kiss of death, but other times the books I choose for these lists live up to my expectations, or surpass them!

(Looking back at the 25 books I selected in January, I see that so far I have read and enjoyed 8, read but been disappointed by 4, not yet read – though they’re on my Kindle or accessible from the library – 9, and not managed to get hold of 4.)

This time around, I’ve chosen 15 books I happen to have heard about that will be released between July and December: 7 fiction and 8 nonfiction. (In release date order within genre. UK release information generally given first, if available. Note given on source if I have managed to get hold of it already.)

Fiction

The Girls Who Grew Big by Leila Mottley [10 July, Fig Tree (Penguin) / June 24, Knopf]: I was impressed with the confident voice in Mottley’s debut, Nightcrawling. She’s just 22 years old so will only keep getting better. This is “about the joys and entanglements of a fierce group of teenage mothers in a small town on the Florida panhandle. … When [16-year-old Adela] tells her parents she’s pregnant, they send her from … Indiana to her grandmother’s in Padua Beach, Florida.” I’ve read one-third so far. (Digital review copy)

The Girls Who Grew Big by Leila Mottley [10 July, Fig Tree (Penguin) / June 24, Knopf]: I was impressed with the confident voice in Mottley’s debut, Nightcrawling. She’s just 22 years old so will only keep getting better. This is “about the joys and entanglements of a fierce group of teenage mothers in a small town on the Florida panhandle. … When [16-year-old Adela] tells her parents she’s pregnant, they send her from … Indiana to her grandmother’s in Padua Beach, Florida.” I’ve read one-third so far. (Digital review copy)

Archive of Unknown Universes by Ruben Reyes Jr. [21 Aug., Footnote Press (Bonnier) / July 1, Mariner Books]: There Is a Rio Grande in Heaven was a strong speculative short story collection and I’m looking forward to his debut novel, which involves alternative history elements. (Starred Kirkus review.) “Cambridge, 2018. Ana and Luis’s relationship is on the rocks, despite their many similarities, including … mothers who both fled El Salvador during the war. In her search for answers, and against her best judgement, Ana uses The Defractor, an experimental device that allows users to peek into alternate versions of their lives.”

Archive of Unknown Universes by Ruben Reyes Jr. [21 Aug., Footnote Press (Bonnier) / July 1, Mariner Books]: There Is a Rio Grande in Heaven was a strong speculative short story collection and I’m looking forward to his debut novel, which involves alternative history elements. (Starred Kirkus review.) “Cambridge, 2018. Ana and Luis’s relationship is on the rocks, despite their many similarities, including … mothers who both fled El Salvador during the war. In her search for answers, and against her best judgement, Ana uses The Defractor, an experimental device that allows users to peek into alternate versions of their lives.”

Minor Black Figures by Brandon Taylor [Oct. 7, Riverhead / 5 March 2026, Jonathan Cape (Penguin)]: I’ve read all of his works … but I’m so glad he’s moving past campus settings now. “A newcomer to New York, Wyeth is a Black painter who grew up in the South and is trying to find his place in the contemporary Manhattan art scene. … When he meets Keating, a white former seminarian who left the priesthood, Wyeth begins to reconsider how to observe the world, in the process facing questions about the conflicts between Black and white art, the white gaze on the Black body, and the compromises we make – in art and in life.” (Edelweiss download)

Minor Black Figures by Brandon Taylor [Oct. 7, Riverhead / 5 March 2026, Jonathan Cape (Penguin)]: I’ve read all of his works … but I’m so glad he’s moving past campus settings now. “A newcomer to New York, Wyeth is a Black painter who grew up in the South and is trying to find his place in the contemporary Manhattan art scene. … When he meets Keating, a white former seminarian who left the priesthood, Wyeth begins to reconsider how to observe the world, in the process facing questions about the conflicts between Black and white art, the white gaze on the Black body, and the compromises we make – in art and in life.” (Edelweiss download)

Heart the Lover by Lily King [16 Oct., Canongate / Oct. 7, Grove Press]: I’ve read several of her books and after Writers & Lovers I’m a forever fan. “In the fall of her senior year of college, [Jordan] meets two star students from her 17th-Century Lit class, Sam and Yash. … she quickly discovers the pleasures of friendship, love and her own intellectual ambition. … when a surprise visit and unexpected news brings the past crashing into the present, Jordan returns to a world she left behind and is forced to confront the decisions and deceptions of her younger self.” (Edelweiss download)

Heart the Lover by Lily King [16 Oct., Canongate / Oct. 7, Grove Press]: I’ve read several of her books and after Writers & Lovers I’m a forever fan. “In the fall of her senior year of college, [Jordan] meets two star students from her 17th-Century Lit class, Sam and Yash. … she quickly discovers the pleasures of friendship, love and her own intellectual ambition. … when a surprise visit and unexpected news brings the past crashing into the present, Jordan returns to a world she left behind and is forced to confront the decisions and deceptions of her younger self.” (Edelweiss download)

Wreck by Catherine Newman [28 Oct., Transworld / Harper]: This is a sequel to Sandwich, and in general sequels should not exist. However, I can make a rare exception. Set two years on, this finds “Rocky, still anxious, nostalgic, and funny, obsessed with a local accident that only tangentially affects them—and with a medical condition that, she hopes, won’t affect them at all.” In a recent Substack post, Newman compared it to Small Rain, my book of 2024, for the focus on a mystery medical condition. (Edelweiss download)

Wreck by Catherine Newman [28 Oct., Transworld / Harper]: This is a sequel to Sandwich, and in general sequels should not exist. However, I can make a rare exception. Set two years on, this finds “Rocky, still anxious, nostalgic, and funny, obsessed with a local accident that only tangentially affects them—and with a medical condition that, she hopes, won’t affect them at all.” In a recent Substack post, Newman compared it to Small Rain, my book of 2024, for the focus on a mystery medical condition. (Edelweiss download)

Palaver by Bryan Washington [Nov. 4, Farrar, Straus, and Giroux / 1 Jan. 2026, Atlantic]: I’ve read all his work and I’m definitely a fan, though I wish that (like Taylor previously) he wouldn’t keep combining the same elements each time. I’ll be reviewing this early for Shelf Awareness; hooray that I don’t have to wait until 2026! “He’s entangled in a sexual relationship with a married man, and while he has built a chosen family in Japan, he is estranged from his family in Houston, particularly his mother … Then, in the weeks leading up to Christmas, ten years since they’ve last seen each other, the mother arrives uninvited on his doorstep. Separated only by the son’s cat, Taro, the two of them bristle against each other immediately.” (Edelweiss download)

Palaver by Bryan Washington [Nov. 4, Farrar, Straus, and Giroux / 1 Jan. 2026, Atlantic]: I’ve read all his work and I’m definitely a fan, though I wish that (like Taylor previously) he wouldn’t keep combining the same elements each time. I’ll be reviewing this early for Shelf Awareness; hooray that I don’t have to wait until 2026! “He’s entangled in a sexual relationship with a married man, and while he has built a chosen family in Japan, he is estranged from his family in Houston, particularly his mother … Then, in the weeks leading up to Christmas, ten years since they’ve last seen each other, the mother arrives uninvited on his doorstep. Separated only by the son’s cat, Taro, the two of them bristle against each other immediately.” (Edelweiss download)

The Silver Book by Olivia Laing [6 Nov., Hamish Hamilton (Penguin) / 11 Nov., Farrar, Straus and Giroux]: I’ve read all but one of Laing’s books and consider her one of our most important contemporary thinkers. I was also pleasantly surprised by Crudo so will be reading this second novel, too. I’ll be reviewing it early for Shelf Awareness as well. “September 1974. Two men meet by chance in Venice. One is a young English artist, in panicked flight from London. The other is Danilo Donati, the magician of Italian cinema. … The Silver Book is at once a queer love story and a noirish thriller, set in the dream factory of cinema. (Edelweiss download)

The Silver Book by Olivia Laing [6 Nov., Hamish Hamilton (Penguin) / 11 Nov., Farrar, Straus and Giroux]: I’ve read all but one of Laing’s books and consider her one of our most important contemporary thinkers. I was also pleasantly surprised by Crudo so will be reading this second novel, too. I’ll be reviewing it early for Shelf Awareness as well. “September 1974. Two men meet by chance in Venice. One is a young English artist, in panicked flight from London. The other is Danilo Donati, the magician of Italian cinema. … The Silver Book is at once a queer love story and a noirish thriller, set in the dream factory of cinema. (Edelweiss download)

Nonfiction

Jesusland: Stories from the Upside[-]Down World of Christian Pop Culture by Joelle Kidd [Aug. 12, ECW]: “Through nine incisive, honest, and emotional essays, Jesusland exposes the pop cultural machinations of evangelicalism, while giving voice to aughts-era Christian children and teens who are now adults looking back at their time measuring the length of their skirts … exploring the pop culture that both reflected and shaped an entire generation of young people.” Yep, that includes me! Looking forward to a mixture of Y2K and Jesus Freak. (NetGalley download)

Jesusland: Stories from the Upside[-]Down World of Christian Pop Culture by Joelle Kidd [Aug. 12, ECW]: “Through nine incisive, honest, and emotional essays, Jesusland exposes the pop cultural machinations of evangelicalism, while giving voice to aughts-era Christian children and teens who are now adults looking back at their time measuring the length of their skirts … exploring the pop culture that both reflected and shaped an entire generation of young people.” Yep, that includes me! Looking forward to a mixture of Y2K and Jesus Freak. (NetGalley download)

Somebody Is Walking on Your Grave: My Cemetery Journeys by Mariana Enríquez; translated from Spanish by Megan McDowell [25 Sept., Granta / Sept. 30, Hogarth]: I’ve enjoyed her creepy short stories, plus I love touring graveyards. “In 2013, when the body of a friend’s mother who was disappeared during Argentina’s military dictatorship was found in a common grave, she began to examine more deeply the complex meanings of cemeteries and where our bodies come to rest. In this vivid, cinematic book … Enriquez travels North and South America, Europe and Australia … [and] investigates each cemetery’s history, architecture, its dead (famous and not), its saints and ghosts, its caretakers and visitors.” (Edelweiss download, for Shelf Awareness review)

Somebody Is Walking on Your Grave: My Cemetery Journeys by Mariana Enríquez; translated from Spanish by Megan McDowell [25 Sept., Granta / Sept. 30, Hogarth]: I’ve enjoyed her creepy short stories, plus I love touring graveyards. “In 2013, when the body of a friend’s mother who was disappeared during Argentina’s military dictatorship was found in a common grave, she began to examine more deeply the complex meanings of cemeteries and where our bodies come to rest. In this vivid, cinematic book … Enriquez travels North and South America, Europe and Australia … [and] investigates each cemetery’s history, architecture, its dead (famous and not), its saints and ghosts, its caretakers and visitors.” (Edelweiss download, for Shelf Awareness review)

Ghosts of the Farm: Two Women’s Journeys Through Time, Land and Community by Nicola Chester [30 Sept., Chelsea Green]: Nicola is our local nature writer and is so wise on class and countryside matters. On Gallows Down was her wonderful debut and, though I know very little about it, I’m looking forward to her second book. “This is the story of Miss White, a woman who lived in the author’s village 80 years ago, a pioneer who realised her ambition to become a farmer during the Second World War. … Moving between Nicola’s own attempts to work outdoors and Miss White’s desire to farm a generation earlier, Nicola explores the parallels between their lives – and the differences.”

Ghosts of the Farm: Two Women’s Journeys Through Time, Land and Community by Nicola Chester [30 Sept., Chelsea Green]: Nicola is our local nature writer and is so wise on class and countryside matters. On Gallows Down was her wonderful debut and, though I know very little about it, I’m looking forward to her second book. “This is the story of Miss White, a woman who lived in the author’s village 80 years ago, a pioneer who realised her ambition to become a farmer during the Second World War. … Moving between Nicola’s own attempts to work outdoors and Miss White’s desire to farm a generation earlier, Nicola explores the parallels between their lives – and the differences.”

Death of an Ordinary Man by Sarah Perry [2 Oct., Vintage (Penguin)]: I’ve had a very mixed experience with Perry’s fiction, but a short bereavement memoir should be right up my street. “Sarah Perry’s father-in-law, David, died at home nine days after a cancer diagnosis and having previously been in the good health. The speed of his illness outstripped that of the NHS and social care, so the majority of nursing fell to Sarah and her husband. They witnessed what happens to the body and spirit, hour by hour, as it approaches death.”

Death of an Ordinary Man by Sarah Perry [2 Oct., Vintage (Penguin)]: I’ve had a very mixed experience with Perry’s fiction, but a short bereavement memoir should be right up my street. “Sarah Perry’s father-in-law, David, died at home nine days after a cancer diagnosis and having previously been in the good health. The speed of his illness outstripped that of the NHS and social care, so the majority of nursing fell to Sarah and her husband. They witnessed what happens to the body and spirit, hour by hour, as it approaches death.”

Book of Lives: A Memoir of Sorts by Margaret Atwood [4 Nov., Vintage (Penguin) / Doubleday]: It’s Atwood; ’nuff said, though I admit I’m daunted by the page count. “Raised by ruggedly independent, scientifically minded parents – entomologist father, dietician mother – Atwood spent most of each year in the wild forest of northern Quebec. … [She links] seminal moments to the books that have shaped our literary landscape. … In pages bursting with bohemian gatherings … and major political turning points, we meet poets, bears, Hollywood actors and larger-than-life characters straight from the pages of an Atwood novel.”

Book of Lives: A Memoir of Sorts by Margaret Atwood [4 Nov., Vintage (Penguin) / Doubleday]: It’s Atwood; ’nuff said, though I admit I’m daunted by the page count. “Raised by ruggedly independent, scientifically minded parents – entomologist father, dietician mother – Atwood spent most of each year in the wild forest of northern Quebec. … [She links] seminal moments to the books that have shaped our literary landscape. … In pages bursting with bohemian gatherings … and major political turning points, we meet poets, bears, Hollywood actors and larger-than-life characters straight from the pages of an Atwood novel.”

Tigers Between Empires: The Improbable Return of Great Cats to the Forests of Russia and China by Jonathan C. Slaght [4 Nov., Allen Lane / Farrar, Straus and Giroux]: Slaght’s Owls of the Eastern Ice was one of the best books I read in 2022; he’s a top-notch nature and travel writer with an environmentalist’s conscience. After the fall of the Soviet Union, “scientists came together to found the Siberian Tiger Project[, which …] captured and released more than 114 tigers over three decades. … [C]haracters, both feline and human, come fully alive as we travel with them through the quiet and changing forests of Amur.” (NetGalley download)

Tigers Between Empires: The Improbable Return of Great Cats to the Forests of Russia and China by Jonathan C. Slaght [4 Nov., Allen Lane / Farrar, Straus and Giroux]: Slaght’s Owls of the Eastern Ice was one of the best books I read in 2022; he’s a top-notch nature and travel writer with an environmentalist’s conscience. After the fall of the Soviet Union, “scientists came together to found the Siberian Tiger Project[, which …] captured and released more than 114 tigers over three decades. … [C]haracters, both feline and human, come fully alive as we travel with them through the quiet and changing forests of Amur.” (NetGalley download)

Joyride by Susan Orlean [6 Nov., Atlantic Books / Oct. 14, Avid Reader Press (Simon & Schuster)]: I’m a fan of Orlean’s genre-busting nonfiction, e.g. The Orchid Thief and The Library Book, and have always wanted to try more by her. “Joyride is her most personal book ever—a searching journey through finding her feet as a journalist, recovering from the excruciating collapse of her first marriage, falling head-over-heels in love again, becoming a mother while mourning the decline of her own mother, sojourning to Hollywood for films based on her work. … Joyride is also a time machine to a bygone era of journalism.”

Joyride by Susan Orlean [6 Nov., Atlantic Books / Oct. 14, Avid Reader Press (Simon & Schuster)]: I’m a fan of Orlean’s genre-busting nonfiction, e.g. The Orchid Thief and The Library Book, and have always wanted to try more by her. “Joyride is her most personal book ever—a searching journey through finding her feet as a journalist, recovering from the excruciating collapse of her first marriage, falling head-over-heels in love again, becoming a mother while mourning the decline of her own mother, sojourning to Hollywood for films based on her work. … Joyride is also a time machine to a bygone era of journalism.”

A Long Game: Notes on Writing Fiction by Elizabeth McCracken [Dec. 2, Ecco]: I’m not big on craft books, but will occasionally read one by an author I admire; McCracken won my heart with The Hero of This Book. “How does one face the blank page? Move a character around a room? Deal with time? Undertake revision? The good and bad news is that in fiction writing, there are no definitive answers. … McCracken … has been teaching for more than thirty-five years [… and] shares insights gleaned along the way, offering practical tips and incisive thoughts about her own work as an artist.” (Edelweiss download)

A Long Game: Notes on Writing Fiction by Elizabeth McCracken [Dec. 2, Ecco]: I’m not big on craft books, but will occasionally read one by an author I admire; McCracken won my heart with The Hero of This Book. “How does one face the blank page? Move a character around a room? Deal with time? Undertake revision? The good and bad news is that in fiction writing, there are no definitive answers. … McCracken … has been teaching for more than thirty-five years [… and] shares insights gleaned along the way, offering practical tips and incisive thoughts about her own work as an artist.” (Edelweiss download)

As a bonus, here are two advanced releases that I reviewed early:

Trying: A Memoir by Chloe Caldwell [Aug. 5, Graywolf] (Reviewed for Foreword): Caldwell devoted much of her thirties to trying to get pregnant via intrauterine insemination. She developed rituals to ease the grueling routine: After every visit, she made a stop for luxury foodstuffs and beauty products. But then her marriage imploded. When she began dating women and her determination to become a mother persisted, a new conception strategy was needed. The book’s fragmentary style suits its aura of uncertainty about the future. Sparse pages host a few sentences or paragraphs, interspersed with wry lists.

Trying: A Memoir by Chloe Caldwell [Aug. 5, Graywolf] (Reviewed for Foreword): Caldwell devoted much of her thirties to trying to get pregnant via intrauterine insemination. She developed rituals to ease the grueling routine: After every visit, she made a stop for luxury foodstuffs and beauty products. But then her marriage imploded. When she began dating women and her determination to become a mother persisted, a new conception strategy was needed. The book’s fragmentary style suits its aura of uncertainty about the future. Sparse pages host a few sentences or paragraphs, interspersed with wry lists. ![]()

If You Love It, Let It Kill You by Hannah Pittard [July 15, Henry Holt] (Reviewed for Shelf Awareness): A quirky work of autofiction about an author/professor tested by her ex-husband’s success, her codependent family, and an encounter with a talking cat. Hana P. (or should that be Pittard?) relishes flouting the “rules” of creative writing. With her affectations and unreliability, she can be a frustrating narrator, but the metafictional angle renders her more wily than precious. The dialogue and scenes sparkle, and there are delightful characters This gleefully odd book is perfect for Miranda July and Patricia Lockwood fans.

If You Love It, Let It Kill You by Hannah Pittard [July 15, Henry Holt] (Reviewed for Shelf Awareness): A quirky work of autofiction about an author/professor tested by her ex-husband’s success, her codependent family, and an encounter with a talking cat. Hana P. (or should that be Pittard?) relishes flouting the “rules” of creative writing. With her affectations and unreliability, she can be a frustrating narrator, but the metafictional angle renders her more wily than precious. The dialogue and scenes sparkle, and there are delightful characters This gleefully odd book is perfect for Miranda July and Patricia Lockwood fans. ![]()

I can also recommend:

Both/And: Essays by Trans and Gender-Nonconforming Writers of Color, ed. Denne Michele Norris [Aug. 12, HarperOne / 25 Sept., HarperCollins] (Review to come for Shelf Awareness) ![]()

Other People’s Mothers by Julie Marie Wade [Sept. 2, Univ. of Florida Press] (Review pending for Foreword) ![]()

Which of these catch your eye? Any other books you’re looking forward to in this second half of the year?

Love Your Library, June 2025

Thank you, as always, to Eleanor, who has put up multiple posts about her recent library reading. My thanks also go to Skai for participating again. Marcie has been taking part in the Toronto Public Library reading challenge Bingo card. I enjoyed seeing in Molly Wizenberg’s latest Substack that she and her child are both doing the Seattle Public Library Summer Book Bingo. I’ve never joined my library system’s adult summer reading challenge because surely it’s meant for non-regular readers. You can sign up to win a prize if you read five or more books – awwww! – and it just wouldn’t seem fair for me to participate.

It’s Pride Month and my library has displays up for it, of course. I got to attend the first annual Queer Folk Festival in London as an ally earlier this month and it was great fun!

Two current initiatives in my library system are pop-up libraries in outlying villages, and a quiet first hour of opening each weekday, meant to benefit those with sensory needs. I volunteer in the first two hours on Tuesdays but haven’t yet noticed lower lighting or it being any quieter than usual.

At the Society of Authors Awards ceremony, Joseph Coelho mentioned that during his time as Waterstones Children’s Laureate, he joined 217 libraries around the country to support their work! (He also built a bicycle out of bamboo and rode it around the south coast.)

I enjoyed this satirical article on The Rumpus about ridding libraries of diversity and inclusion practices. My favourite line: “The ‘Diverse Discussions’ book club will be renamed ‘Not Woke Folk (Tales).’”

And finally, I discovered evidence of my first bout of library volunteering (in Bowie, Maryland, for a middle school requirement) in my mother’s journal entry from 20 April 1996: “Rebecca started her Community Service this a.m., 10 – 12 noon, at the Library. She learned to put children’s books on the cart by sorting them.”

My library use over the last month:

(links are to books not already reviewed on the blog)

READ

- Good Girl by Aria Aber

- Moving the Millers’ Minnie Moore Mine Mansion by Dave Eggers

- Self-Portrait with Family by Amaan Hyder

- May Day by Jackie Kay

- Spring: The Story of a Season by Michael Morpurgo

- The Age of Diagnosis: Sickness, Health and Why Medicine Has Gone Too Far by Suzanne O’Sullivan

SKIMMED

- Period Power: Harness Your Hormones and Get Your Cycle Working for You by Maisie Hill

- Is a River Alive? by Robert Macfarlane

CURRENTLY READING

- Don’t Forget We’re Here Forever: A New Generation’s Search for Religion by Lamorna Ash

- The Honesty Box by Lucy Brazier

- Bellies by Nicola Dinan

- To the Edge of the Sea: Schooldays of a Crofter’s Child by Christina Hall

- The Secret Lives of Booksellers and Librarians: True Stories of the Magic of Reading by James Patterson & Matt Eversmann

- Ripeness by Sarah Moss

CHECKED OUT, TO BE READ

- Fulfillment by Lee Cole

- Adam by Gboyega Odubanjo

- The Forgotten Sense: The Nose and the Perception of Smell by Jonas Olofsson

- Enchanted Ground: Growing Roots in a Broken World by Steven Lovatt

- Boiled Owls by Azad Ashim Sharma

- The Artist by Lucy Steeds

+ various Berlin and Germany guides to plan a September trip

ON HOLD, TO BE COLLECTED

- The Most by Jessica Anthony

- Atmosphere by Taylor Jenkins Reid

- Three Weeks in July by Adam Wishart & James Nally

IN THE RESERVATION QUEUE

- Terrible Horses by Raymond Antrobus

- The Interpretation of Cats: And Their Owners by Claude Béata; translated by David Watson

- The Boy, the Troll and the Chalk by Anne Booth (whom I met at the SoA Awards ceremony)

- The Husbands by Holly Gramazio

- Albion by Anna Hope

- Fragile Minds by Bella Jackson

- The Homemade God by Rachel Joyce

- The Names by Florence Knapp

- Shattered by Hanif Kureishi

- Wife by Charlotte Mendelson

- The Eights by Joanna Miller

RETURNED UNFINISHED

- Normally Weird and Weirdly Normal: My Adventures in Neurodiversity by Robin Ince – His rambling stories work better in person (I really enjoyed seeing him in Hungerford on the tour promoting this book) than in print. I read about 66 pages.

- The Persians by Sanam Mahloudji – I only read the first few pages of this Women’s Prize shortlistee and it seemed flippant and unnecessary.

RETURNED UNREAD

- Day by Michael Cunningham – I’ll get it back out another time.

- Looking After: A Portrait of My Autistic Brother by Caroline Elton – This was requested off of me; I might get it back out another time.

- Rebel Bodies: A Guide to the Gender Health Gap Revolution by Sarah Graham – I lost interest and needed to make space on my card.

- The Kingdoms by Natasha Pulley – I thought I’d try this because it has an Outer Hebrides setting, but I couldn’t get into the first few pages and didn’t want to pack a chunky paperback that might not work out for me.

- Horse by Rushika Wick – I needed to make space on my card plus this didn’t really look like my sort of poetry.

What have you been reading or reviewing from the library recently?

Share a link to your own post in the comments. Feel free to use the above image. The hashtag is #LoveYourLibrary.

Although her choices are indisputable classics, she acknowledges they can only ever be an incomplete and biased selection, unfortunately all white and largely male, though she opens with

Although her choices are indisputable classics, she acknowledges they can only ever be an incomplete and biased selection, unfortunately all white and largely male, though she opens with

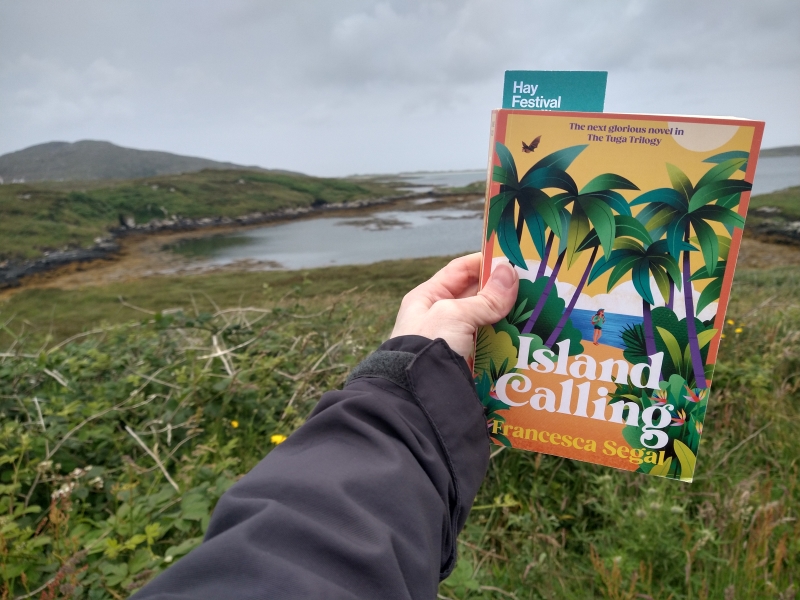

Often, there is a hint of menace, whether the topic is salmon fishing, raspberry picking or the history of a lost ring. “The Clear and Rolling Water” has the atmosphere of a Scottish folk ballad, which made it perfect reading for our recent

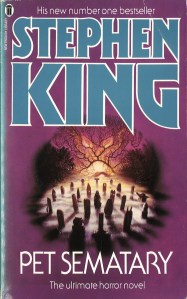

Often, there is a hint of menace, whether the topic is salmon fishing, raspberry picking or the history of a lost ring. “The Clear and Rolling Water” has the atmosphere of a Scottish folk ballad, which made it perfect reading for our recent  I’d only ever read King’s On Writing and worried I wouldn’t be able to handle his fiction. I could never watch a horror film, but somehow the same content was okay in print. For half the length or more, it’s more of a mildly dread-laced, John Irving-esque novel about how we deal with the reality of death. Dr. Louis Creed and his family – wife Rachel, five-year-old daughter Ellie, two-year-old son Gage and cat Church (short for Winston Churchill) – have recently moved from Chicago to Maine for him to take up a post as head of University Medical Services. Their 83-year-old neighbour across the street, Judson Crandall, becomes a sort of surrogate father to Louis, warning them about the dangerous highway that separates their houses and initiating them with a tour of the pet cemetery and Micmac burial ground that happen to be on their property. Things start getting weird early on: Louis’s first day on the job sees a student killed by a car while jogging; the young man’s cryptic dying words are about the pet cemetery, and he then visits Louis in a particularly vivid dream.

I’d only ever read King’s On Writing and worried I wouldn’t be able to handle his fiction. I could never watch a horror film, but somehow the same content was okay in print. For half the length or more, it’s more of a mildly dread-laced, John Irving-esque novel about how we deal with the reality of death. Dr. Louis Creed and his family – wife Rachel, five-year-old daughter Ellie, two-year-old son Gage and cat Church (short for Winston Churchill) – have recently moved from Chicago to Maine for him to take up a post as head of University Medical Services. Their 83-year-old neighbour across the street, Judson Crandall, becomes a sort of surrogate father to Louis, warning them about the dangerous highway that separates their houses and initiating them with a tour of the pet cemetery and Micmac burial ground that happen to be on their property. Things start getting weird early on: Louis’s first day on the job sees a student killed by a car while jogging; the young man’s cryptic dying words are about the pet cemetery, and he then visits Louis in a particularly vivid dream.

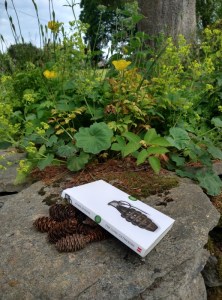

Rightly likened to Of Mice and Men, this is an engrossing short novel about two brothers, Neil and Calum, tasked with climbing trees and gathering the pinecones of a wealthy Scottish estate. They will be used to replant the many woodlands being cut down to fuel the war effort. Calum, the younger brother, is physically and intellectually disabled but has a deep well of compassion for living creatures. He has unwittingly made an enemy of the estate’s gamekeeper, Duror, by releasing wounded rabbits from his traps. Much of the story is taken up with Duror’s seemingly baseless feud against the brothers – though we’re meant to understand that his bedbound wife’s obesity and his subsequent sexual frustration may have something to do with it – as well as with Lady Runcie-Campbell’s class prejudice. Her son, Roderick, is an unexpected would-be hero and voice of pure empathy. I read this quickly, with grim fascination, knowing tragedy was coming but not quite how things would play out. The introduction to Canongate’s Canons Collection edition is by actor Paul Giamatti, of all people. (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project, Newbury)

Rightly likened to Of Mice and Men, this is an engrossing short novel about two brothers, Neil and Calum, tasked with climbing trees and gathering the pinecones of a wealthy Scottish estate. They will be used to replant the many woodlands being cut down to fuel the war effort. Calum, the younger brother, is physically and intellectually disabled but has a deep well of compassion for living creatures. He has unwittingly made an enemy of the estate’s gamekeeper, Duror, by releasing wounded rabbits from his traps. Much of the story is taken up with Duror’s seemingly baseless feud against the brothers – though we’re meant to understand that his bedbound wife’s obesity and his subsequent sexual frustration may have something to do with it – as well as with Lady Runcie-Campbell’s class prejudice. Her son, Roderick, is an unexpected would-be hero and voice of pure empathy. I read this quickly, with grim fascination, knowing tragedy was coming but not quite how things would play out. The introduction to Canongate’s Canons Collection edition is by actor Paul Giamatti, of all people. (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project, Newbury)

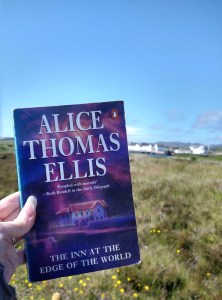

Eric and Mabel moved from the Midlands to run a hotel on a remote Scottish island. He places an advertisement in select London periodicals to lure in some Christmas-haters for the holidays and attracts a motley group: a bereaved former soldier writing a biography of General Gordon, a pair of actors known only for commercials, a psychoanalyst, and a department store buyer looking for a novel sweater pattern. Mabel decides she’s had enough and flees the island just as the guests start arriving. One guest is stalking another; one has history on the island. And all along, there are hints that this is a site of major selkie activity. I found it jarring how the novella moved from Shena Mackay-like social comedy into magic realism and doubt I’ll read more by Ellis (I’d already read one volume of

Eric and Mabel moved from the Midlands to run a hotel on a remote Scottish island. He places an advertisement in select London periodicals to lure in some Christmas-haters for the holidays and attracts a motley group: a bereaved former soldier writing a biography of General Gordon, a pair of actors known only for commercials, a psychoanalyst, and a department store buyer looking for a novel sweater pattern. Mabel decides she’s had enough and flees the island just as the guests start arriving. One guest is stalking another; one has history on the island. And all along, there are hints that this is a site of major selkie activity. I found it jarring how the novella moved from Shena Mackay-like social comedy into magic realism and doubt I’ll read more by Ellis (I’d already read one volume of

The many Gaelic phrases, defined in footnotes, help to create the atmosphere. The chapter epigraphs from the legend of Oisín (son of Fionn Mac Cumhaill) and Tír Na nÓg, the land of eternal youth, heighten the contrast between Colin’s idealism and the reality of this life-changing season. I think this is the first book I’ve read that was originally published in Gaelic and I hope it will find readers far beyond its island niche. (BookSirens)

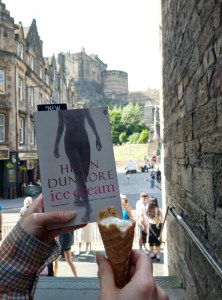

The many Gaelic phrases, defined in footnotes, help to create the atmosphere. The chapter epigraphs from the legend of Oisín (son of Fionn Mac Cumhaill) and Tír Na nÓg, the land of eternal youth, heighten the contrast between Colin’s idealism and the reality of this life-changing season. I think this is the first book I’ve read that was originally published in Gaelic and I hope it will find readers far beyond its island niche. (BookSirens)  1) Our transit through Edinburgh was brief and muggy, but we made sure to leave just enough time to queue for cones at Mary’s Milk Bar, which has the most interesting flavours you’ll find anywhere. Pictured, though half eaten, are my one scoop of Earl Grey and peach sorbet and one scoop of fig and cardamom ice cream. When we returned to Edinburgh to return the car at the end of our trip, I took the train home by myself but C stayed on for a conference, during which he treated himself to another round at Mary’s.

1) Our transit through Edinburgh was brief and muggy, but we made sure to leave just enough time to queue for cones at Mary’s Milk Bar, which has the most interesting flavours you’ll find anywhere. Pictured, though half eaten, are my one scoop of Earl Grey and peach sorbet and one scoop of fig and cardamom ice cream. When we returned to Edinburgh to return the car at the end of our trip, I took the train home by myself but C stayed on for a conference, during which he treated himself to another round at Mary’s.

A quaint short memoir set in the 1950s on the island of Mull (which we sailed past on our way to and from the Outer Hebrides). It’s narrated in tongue-in-cheek fashion by Nicholas the Cat, who pals around with the farm’s dogs, horse and goats and comments on the doings of its human inhabitants, such as “Puddy” (Carothers), a war widow, and her daughter Fionna, who goes away to school. “We understand so much about them, yet they understand so little about us,” he opines. Indeed, the animals are all observant and can communicate with each other. Corrieshellach is a fine horse taken to compete in shows. The goats are lucky to escape with their lives after a local outbreak of foot-and-mouth disease among livestock. Nicholas grows fat on rabbits and fathers several litters. He voices some traditional views (the Clearances: bad but the Empire: good; crows: bad); then again, cats would certainly be C/conservatives. A sweet Blyton-esque read for precocious children or sentimental adults, this passed the time nicely on a long drive. It could do with a better title, though; the ducks only play a tiny role. (Favourite aside: “that beverage which humans find so comforting when things aren’t right. Tea.”) (Secondhand – Benbecula thrift shop)

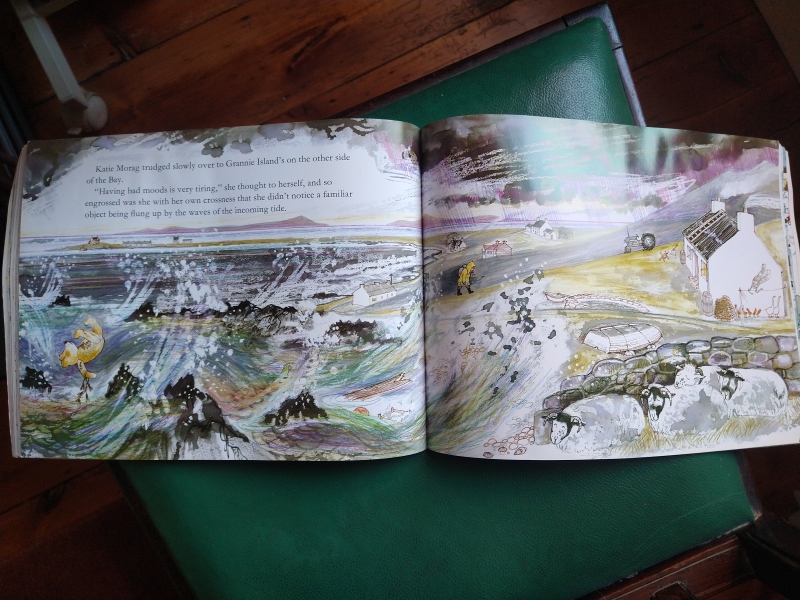

A quaint short memoir set in the 1950s on the island of Mull (which we sailed past on our way to and from the Outer Hebrides). It’s narrated in tongue-in-cheek fashion by Nicholas the Cat, who pals around with the farm’s dogs, horse and goats and comments on the doings of its human inhabitants, such as “Puddy” (Carothers), a war widow, and her daughter Fionna, who goes away to school. “We understand so much about them, yet they understand so little about us,” he opines. Indeed, the animals are all observant and can communicate with each other. Corrieshellach is a fine horse taken to compete in shows. The goats are lucky to escape with their lives after a local outbreak of foot-and-mouth disease among livestock. Nicholas grows fat on rabbits and fathers several litters. He voices some traditional views (the Clearances: bad but the Empire: good; crows: bad); then again, cats would certainly be C/conservatives. A sweet Blyton-esque read for precocious children or sentimental adults, this passed the time nicely on a long drive. It could do with a better title, though; the ducks only play a tiny role. (Favourite aside: “that beverage which humans find so comforting when things aren’t right. Tea.”) (Secondhand – Benbecula thrift shop)  I read half of this large-format paperback before our trip and the rest afterward. It collects four of Hedderwick’s picture books, which are all set on the Isle of Struay, a kind of Hebridean composite that reproduces the islands’ wildlife and scenery beautifully. Katie Morag’s parents run the shop and post office and her mother always seems to be producing another little brother. In Katie Morag Delivers the Mail, the little red-haired girl causes chaos by delivering parcels at random. Sophisticated Granma Mainland and practical Grannie Island are the stars of Katie Morag and the Two Grandmothers. Katie Morag learns to deal with her anger and with being punished, respectively, in …and the Tiresome Ted and …and the Big Boy Cousins. Cute stories with useful lessons, but the illustrations are the main attraction. I’ll get the rest of the books out from the library. (Little Free Library)

I read half of this large-format paperback before our trip and the rest afterward. It collects four of Hedderwick’s picture books, which are all set on the Isle of Struay, a kind of Hebridean composite that reproduces the islands’ wildlife and scenery beautifully. Katie Morag’s parents run the shop and post office and her mother always seems to be producing another little brother. In Katie Morag Delivers the Mail, the little red-haired girl causes chaos by delivering parcels at random. Sophisticated Granma Mainland and practical Grannie Island are the stars of Katie Morag and the Two Grandmothers. Katie Morag learns to deal with her anger and with being punished, respectively, in …and the Tiresome Ted and …and the Big Boy Cousins. Cute stories with useful lessons, but the illustrations are the main attraction. I’ll get the rest of the books out from the library. (Little Free Library)