Blurb Your Enthusiasm by Louise Willder

At last, I’m caught up reviewing September releases! It’s one of the busier months in the publishing calendar, so I shouldn’t be surprised that I had such a bounteous crop. Now I can pay more attention to R.I.P. selections, catching up on others’ blog posts, and getting ahead before the start of Novellas in November.

Blurb Your Enthusiasm is a delightful bibliophile’s miscellany with a great title – not just for the play on words, but also for how it encapsulates what this is about: ways of pithily spreading excitement about books. The first part of the subtitle, “An A–Z of Literary Persuasion,” is puzzling in that the structure is scattershot rather than strictly alphabetical, but the second is perfect: from the title and cover to the contents, Louise Willder is interested in what convinces people to acquire and read a book.

Over the last 25 years, she has written the jacket copy for thousands of Penguin releases, so she has it down to a science as well as an art. Book reviewing seems to me to be an adjacent skill. I know from nine years of freelance writing about books, in which I’ve had to produce reviews ranging from 100 to 2,000 words, that the shortest and most formulaic reviews can be the most difficult to compose, but are also excellent writing discipline. As Willder puts it, “Writing short, for whatever reason you do it, forces rigour, and it reminds you that words are a precious and powerful resource. Form both limits and liberates.”

How to do justice to the complexity of several hundred pages of an author’s hard work in just 150 words or so? How to suggest the tone and contents without a) resorting to clichés (“luminous” and “unflinching” are a couple of my bugbears), b) giving too much away, c) overstating the case, or misleading anyone about the merits of a Marmite book, or d) committing the cardinal sin of boring readers before they’ve even opened to the first page?

it can be easy to forget that a potential reader hasn’t read it: they don’t know anything about it. You can’t sell them the experience of the book – you have to sell them the expectation of reading it; the idea of it. And that’s when a copywriter can be an author’s best friend.

[An aside: Literary critics and blog reviewers generally see themselves as having different roles: making objective (pah!) pronouncements about literary value versus cheerleading for the books they love and want others to discover (a sort of unpaid partnership with publicists). I’m in the odd position of being both, and feel I engage in the two activities pretty much equally, perhaps leaning more towards the former. There’s some crossover, of course, with bloggers such as myself happy to publish the occasional more critical review. But we aren’t generally, as Willder is, in the business of selling books, so unless we’re pals with the author on Twitter we don’t tend to have a vested interest in seeing the book do well.]

Each reader will home in on certain topics here: the art of the first line, Dickens’s serialization and self-promotion, Orwell’s guidelines for good writing, the differences between British and American jacket copy, the use of punctuation, and so much more. I particularly loved the mock and bad blurbs she cites (we’ve both commented on the ludicrous one for The Country Girls!), including one an AI created for this book, and her rundown of the conventions of blurb-writing for various genres, everything from children’s books to science fiction. She frequently breaks her own rules (e.g., she’s anti-adjective and -ellipses, yet I found five of the one and two of the other in the Crace blurb; see below) and is very funny to boot.

Here’s some of the bookish and word-nerd trivia that captivated me:

- J. D. Salinger didn’t allow blurbs on his books.

- The American usage of the word “blurb” is for advance review quotes that fellow authors contribute for inclusion on the cover. I didn’t realize I used the word interchangeably for either meaning; in the UK, one might call such a quote a “puff.”

- Marshall McLuhan invented the “page 69 test” – to decide whether you want to buy/read a book, turn to that page instead of (or maybe in addition to) looking at the first paragraph.

- A New York publishing CEO once joked that Lincoln’s Doctor’s Dog would be an optimal title to appeal to readers (respected president + health + animal), but there are actually now six books bearing some variation on that title and all were presumably flops!

- “Wackaging” is the word for quirky marketing that has products talk to us (Innocent Smoothies, established in 1999, is thought to have started the trend).

- I pulled out my copy of Jim Crace’s Quarantine to see how Willder managed to write a blurb about a novel about Jesus without mentioning Jesus (“a Galilean who they say has the power to work miracles”)!

Some more favourite lines:

“There’s always something to love and learn from in a book, especially if it lasts as long as these books [children’s classics] have, and part of the job of people like me is to pick out what makes it special and pass it on.”

“always ask yourself, what’s really going on here? Why should anyone care? And how do we make them care?”

For all of us who value books, whether we write about them or not, those seem like important points to remember. We read to learn, but also to feel, and when we share our love of books with other people we can do so on the basis of how they have engaged our brains and hearts. This was thoroughly entertaining and has prompted me to pay that bit more attention to the few paragraphs on the inside of a book jacket. (See also Susan’s review.)

With thanks to Oneworld for the free copy for review.

The Blind Assassin Reread for #MARM, and Other Doorstoppers

It’s the fourth annual Margaret Atwood Reading Month (#MARM), hosted by Canadian blogger extraordinaire Marcie of Buried in Print. In previous years, I’ve read Surfacing and The Edible Woman, The Robber Bride and Moral Disorder, and Wilderness Tips. This year Laila at Big Reading Life and I did a buddy reread of The Blind Assassin, which was historically my favourite Atwood novel. I’d picked up a free paperback the last time I was at The Book Thing of Baltimore. Below are some quick thoughts based on what I shared with Laila as I was reading.

The Blind Assassin (2000)

Winner of the Booker Prize and Hammett Prize; shortlisted for the Orange Prize

I must have first read this about 13 years ago. The only thing I remembered before I started my reread was that there is a science fiction book-within-the-book. I couldn’t recall anything else about the setup before I read in the blurb about the suspicious circumstances of Laura’s death in 1945. Indeed, the opening line, which deserves to be famous, is “Ten days after the war ended, my sister Laura drove a car off a bridge.”

I always love novels about sisters, and Iris is a terrific narrator. Now a cantankerous elderly woman, she takes us back through her family history: her father’s button factory and his clashes with organizing workers, her mother’s early death, and her enduring relationship with their housekeeper, Reenie. Iris and Laura met a young man named Alex Thomas, a war orphan with radical views, at the factory’s Labour Day picnic, and it was clear early on that Laura was smitten, while Iris went on to marry Richard Griffen, a nouveau riche industrialist.

Interspersed with Iris’s recollections are newspaper articles that give a sense that the Chase family might be cursed, and excerpts from The Blind Assassin, Laura’s posthumously published novel. Daring for its time in terms of both explicit content and literary form (e.g., no speech marks), it has a storyline rather similar to 1984, with an upper-crust woman having trysts with a working-class man in his squalid lodgings. During their time snatched together, he also tells her a story inspired by the pulp sci-fi of the time. I was less engaged by the story-within-the-story(-within-the-story) this time around compared to Iris’s current life and flashbacks.

In the back of my mind, I had a vague notion that there was a twist coming, and in my impatience to see if I was right I ended up skimming much of the second half of the novel. My hunch was proven correct, but I was disappointed with myself that I wasn’t able to enjoy the journey more a second time around. Overall, this didn’t wow me on a reread, but then again, I am less dazzled by literary “tricks” these days. At the sentence level, however, the writing was fantastic, including descriptions of places, seasons and characters’ psychology. It’s intriguing to think about whether we can ever truly know Laura given Iris’s guardianship of her literary legacy.

If you haven’t read this before, find a time when you can give it your full attention and sink right in. It’s so wise on family secrets and the workings of memory and celebrity, and the weaving in of storylines in preparation for the big reveal is masterful.

Some favourite passages:

“What fabrications they are, mothers. Scarecrows, wax dolls for us to stick pins into, crude diagrams. We deny them an existence of their own, we make them up to suit ourselves – our own hungers, our own wishes, our own deficiencies.”

“Beginnings are sudden, but also insidious. They creep up on you sideways, they keep to the shadows, they lurk unrecognized. Then, later, they spring.”

“The only way you can write the truth is to assume that what you set down will never be read. Not by any other person, and not even by yourself at some later date. Otherwise you begin excusing yourself. You must see the writing as emerging like a long scroll of ink from the index finger of your right hand; you must see your left hand erasing it. Impossible, of course.”

My original rating (c. 2008):

My rating now:

What to read for #MARM next year, I wonder??

In general, I have been struggling mightily with doorstoppers this year. I just don’t seem to have the necessary concentration, so Novellas in November has been a boon. I’ve been battling with Ruth Ozeki’s latest novel for months, and another attempted buddy read of 460 pages has also gone by the wayside. I’ll write a bit more on this for #LoveYourLibrary on Monday, including a couple of recent DNFs. The Blind Assassin was only my third successful doorstopper of the year so far. After The Absolute Book, the other one was:

The Lincoln Highway by Amor Towles

In Towles’ third novel – a big, old-fashioned dose of Americana – brothers and pals set out from Nebraska on road and rail adventures to find a fortune in 1950s New York. The book features some fantastic characters. Precocious Billy steals every scene he appears in. Duchess is a delightfully flamboyant bounder, peppering his speech with malapropisms and Shakespeare quotes. However, Emmett is a dull protagonist, and it’s disappointing that Sally, one of just two main female characters, plays such a minor role. A danger with an episodic narrative is that random events and encounters pile up but don’t do much to further the plot. At nearly 200 pages in, I realized little of consequence had happened yet. A long road, then, with some ups and downs along the way, but Towles’ fans will certainly want to sign up for the ride.

In Towles’ third novel – a big, old-fashioned dose of Americana – brothers and pals set out from Nebraska on road and rail adventures to find a fortune in 1950s New York. The book features some fantastic characters. Precocious Billy steals every scene he appears in. Duchess is a delightfully flamboyant bounder, peppering his speech with malapropisms and Shakespeare quotes. However, Emmett is a dull protagonist, and it’s disappointing that Sally, one of just two main female characters, plays such a minor role. A danger with an episodic narrative is that random events and encounters pile up but don’t do much to further the plot. At nearly 200 pages in, I realized little of consequence had happened yet. A long road, then, with some ups and downs along the way, but Towles’ fans will certainly want to sign up for the ride.

See my full review for BookBrowse; see also my related article on Studebaker cars.

With thanks to Hutchinson for the free copy for review.

Anything by Atwood, or any doorstoppers, on your pile recently?

Three May Graphic Novel Releases: Orwell, In, and Coma

These three terrific graphic novels all have one-word titles and were published on the 13th of May. Outwardly, they are very different: a biography of a famous English writer, the story of an artist looking for authentic connections, and a memoir of a medical crisis that had permanent consequences. The drawing styles are varied as well. But if the books share one thing, it’s an engagement with loneliness: It’s tempting to see the self as being pitted against the world, with illness an additional isolating force, but family, friends and compatriots are there to help us feel less alone and like we are a part of something constructive.

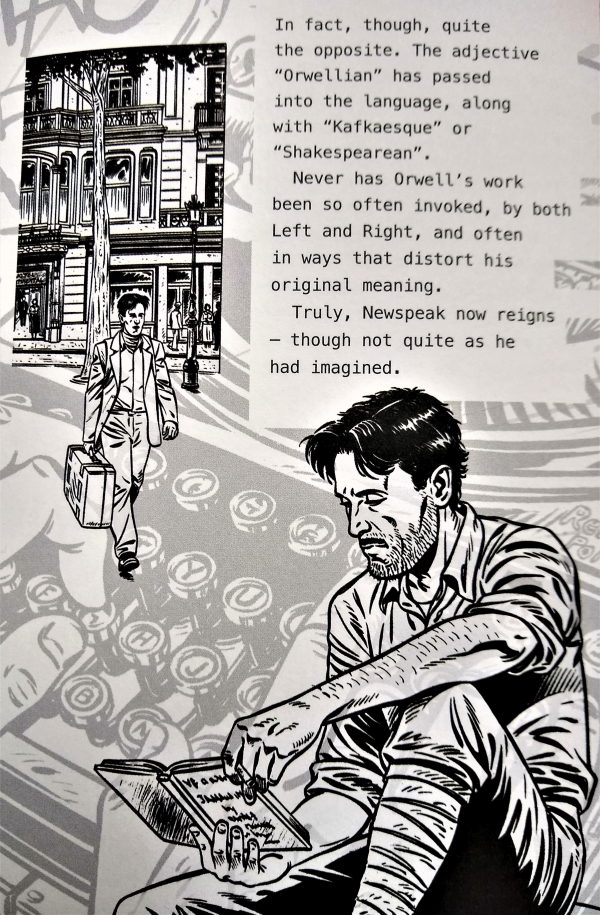

Orwell by Pierre Christin; illustrated by Sébastien Verdier

[Translated from the French by Edward Gauvin]

George Orwell was born Eric Blair in Bengal, where his father worked for the colonial government. As a boy, he loved science fiction and knew that he would become a writer. He had an unhappy time at prep school, where he was on reduced fees, and proceeded to Eton and then police training in Burma. Already he felt that “imperialism was an evil thing.” Among this book’s black-and-white panes, the splashes of colour – blood, a British flag – stand out, and guest artists contribute a two-page colour spread each, illustrating scenes from Orwell’s major works. His pen name commemorates a local river and England’s patron saint, marking his preoccupation with the essence of Englishness: something deeper than his hated militarism and capitalism. Even when he tried to ‘go native’ for embedded journalism (Down and Out in Paris and London and The Road to Wigan Pier), his accent marked him out as posh. He was opinionated and set out “rules” for clear writing and the proper making of tea.

George Orwell was born Eric Blair in Bengal, where his father worked for the colonial government. As a boy, he loved science fiction and knew that he would become a writer. He had an unhappy time at prep school, where he was on reduced fees, and proceeded to Eton and then police training in Burma. Already he felt that “imperialism was an evil thing.” Among this book’s black-and-white panes, the splashes of colour – blood, a British flag – stand out, and guest artists contribute a two-page colour spread each, illustrating scenes from Orwell’s major works. His pen name commemorates a local river and England’s patron saint, marking his preoccupation with the essence of Englishness: something deeper than his hated militarism and capitalism. Even when he tried to ‘go native’ for embedded journalism (Down and Out in Paris and London and The Road to Wigan Pier), his accent marked him out as posh. He was opinionated and set out “rules” for clear writing and the proper making of tea.

The book’s settings range from Spain, where Orwell went to fight in the Civil War, via a bomb shelter in London’s Underground, to the island of Jura, where he retired after the war. I particularly loved the Scottish scenery. I also appreciated the notes on where his life story entered into his fiction (especially in A Clergyman’s Daughter and Keep the Aspidistra Flying). During World War II he joined the Home Guard and contributed to BBC broadcasting alongside T.S. Eliot. He had married Eileen, adopted a baby boy, and set up a smallholding. Even when hospitalized for tuberculosis, he wouldn’t stop typing (or smoking).

Christin creates just enough scenes to give a sense of the sweep of Orwell’s life, and incorporates plenty of the author’s own words in a typewriter font. He recognizes all the many aspects, sometimes contradictory, of his subject’s life. And in an afterword, he makes a strong case for Orwell’s ideas being more important now than ever before. My knowledge of Orwell’s oeuvre, apart from the ones everyone has read – Animal Farm and 1984 – is limited; luckily this is suited not just to Orwell fans but to devotees of life stories of any kind.

Christin creates just enough scenes to give a sense of the sweep of Orwell’s life, and incorporates plenty of the author’s own words in a typewriter font. He recognizes all the many aspects, sometimes contradictory, of his subject’s life. And in an afterword, he makes a strong case for Orwell’s ideas being more important now than ever before. My knowledge of Orwell’s oeuvre, apart from the ones everyone has read – Animal Farm and 1984 – is limited; luckily this is suited not just to Orwell fans but to devotees of life stories of any kind.

With thanks to SelfMadeHero for the free copy for review.

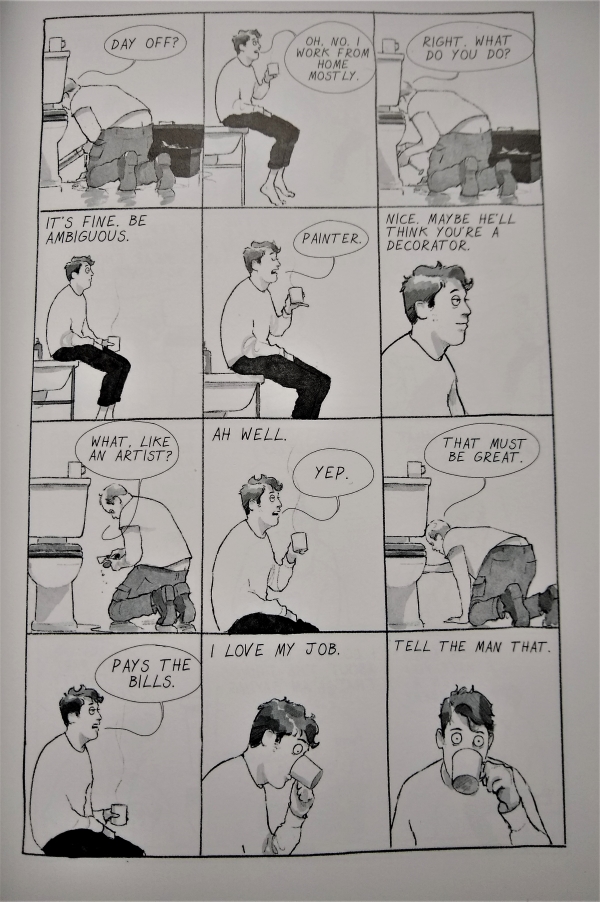

In by Will McPhail

Nick never knows the right thing to say. The bachelor artist’s well-intentioned thoughts remain unvoiced, such that all he can manage is small talk. Whether he’s on a subway train, interacting with his mom and sister, or sitting in a bar with a tongue-in-cheek name (like “Your Friends Have Kids” or “Gentrificchiato”), he’s conscious of being the clichéd guy who’s too clueless or pathetic to make a real connection with another human being. That starts to change when he meets Wren, a Black doctor who instantly sees past all his pretence.

Like Orwell, In makes strategic use of colour spreads. “Say something that matters,” Nick scolds himself, and on the rare occasions when he does figure out what to say or ask – the magic words that elicit an honest response – it’s as if a new world opens up. These full-colour breakthrough scenes are like dream sequences, filled with symbols such as a waterfall, icy cliff, or half-submerged building with classical façade. Each is heralded by a close-up image on the other person’s eyes: being literally close enough to see their eye colour means being metaphorically close enough to be let in. Nick achieves these moments with everyone from the plumber to his four-year-old nephew.

Like Orwell, In makes strategic use of colour spreads. “Say something that matters,” Nick scolds himself, and on the rare occasions when he does figure out what to say or ask – the magic words that elicit an honest response – it’s as if a new world opens up. These full-colour breakthrough scenes are like dream sequences, filled with symbols such as a waterfall, icy cliff, or half-submerged building with classical façade. Each is heralded by a close-up image on the other person’s eyes: being literally close enough to see their eye colour means being metaphorically close enough to be let in. Nick achieves these moments with everyone from the plumber to his four-year-old nephew.

Alternately laugh-out-loud funny and tender, McPhail’s debut novel is as hip as it is genuine. It’s a spot-on picture of modern life in a generic city. I especially loved the few pages when Nick is on a Zoom call with carefully ironed shirt but no trousers and the potential employers on the other end get so lost in their own jargon that they forget he’s there. His banter with Wren or with his sister reveals a lot about these characters, but there’s also an amazing 12-page wordless sequence late on that conveys so much. While I’d recommend this to readers of Alison Bechdel, Craig Thompson, and Chris Ware (and expect it to have a lot in common with Kristen Radtke’s forthcoming Seek You: A Journey through American Loneliness), it’s perfect for those brand new to graphic novels, too – a good old-fashioned story, with all the emotional range of Writers & Lovers. I hope it’ll be a wildcard entry on the Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award shortlist.

With thanks to Sceptre for the free copy for review.

Coma by Zara Slattery

In May 2013, Zara Slattery’s life changed forever. What started as a nagging sore throat developed into a potentially deadly infection called necrotising fascitis. She spent 15 days in a medically induced coma and woke up to find that one of her legs had been amputated. As in Orwell and In, colour is used to differentiate different realms. Monochrome sketches in thick crayon illustrate her husband Dan’s diary of the everyday life that kept going while she was in hospital, yet it’s the coma/fantasy pages in vibrant blues, reds and gold that feel more real.

Slattery remembers, or perhaps imagines, being surrounded by nightmarish skulls and menacing animals. She feels accused and guilty, like she has to justify her continued existence. In one moment she’s a puppet; in another she’s in ancient China, her fate being decided for her. Some of the watery landscapes and specific images here happen to echo those in McPhail’s novel: a splash park, a sunken theatre; a statue on a plinth. There’s also a giant that reminded me a lot of one of the monsters in Spirited Away.

Slattery remembers, or perhaps imagines, being surrounded by nightmarish skulls and menacing animals. She feels accused and guilty, like she has to justify her continued existence. In one moment she’s a puppet; in another she’s in ancient China, her fate being decided for her. Some of the watery landscapes and specific images here happen to echo those in McPhail’s novel: a splash park, a sunken theatre; a statue on a plinth. There’s also a giant that reminded me a lot of one of the monsters in Spirited Away.

Meanwhile, Dan was holding down the fort, completing domestic tasks and reassuring their three children. Relatives came to stay; neighbours brought food, ran errands, and gave him lifts to the hospital. He addresses the diary directly to Zara as a record of the time she spent away from home and acknowledges that he doesn’t know if she’ll come back to them. A final letter from Zara’s nurse reveals how bad off she was, maybe more so than Dan was aware.

This must have been such a distressing time to revisit. In this interview, Slattery talks about the courage it took to read Dan’s diary even years after the fact. I admired how the book’s contrasting drawing styles recreate her locked-in mental state and her family’s weeks of waiting – both parties in limbo, wondering what will come next.

Brighton, where Slattery is based, is a hotspot of the Graphic Medicine movement spearheaded by Ian Williams (author of The Lady Doctor). Regular readers know how much I love health narratives, and with my keenness for graphic novels this series couldn’t be better suited to my interests.

With thanks to Myriad Editions for the free copy for review.

Read any graphic novels recently?

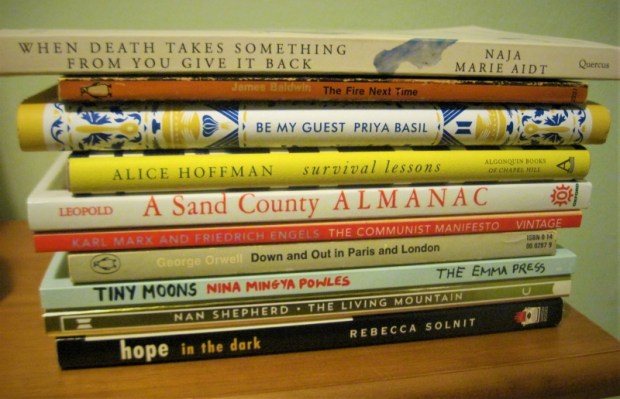

10 Favorite Nonfiction Novellas from My Shelves

What do I mean by a nonfiction novella? I’m not claiming a new genre like Truman Capote did for the nonfiction novel (so unless they’re talking about In Cold Blood or something very similar, yes, I can and do judge people who refer to a memoir as a “nonfiction novel”!); I’m referring literally to any works of nonfiction shorter than 200 pages. Many of my selections even come well under 100 pages.

I’m kicking off this nonfiction-focused week of Novellas in November with a rundown of 10 of my favorite short nonfiction works. Maybe you’ll find inspiration by seeing the wide range of subjects covered here: bereavement, social and racial justice, hospitality, cancer, nature, politics, poverty, food and mountaineering. I’d reviewed all but one of them on the blog, half of them as part of Novellas in November in various years.

When Death Takes Something from You Give It Back: Carl’s Book by Naja Marie Aidt [137 pages]: In March 2015 Aidt got word that her son Carl Emil was dead. The 25-year-old jumped out of his fifth-floor Copenhagen window after taking some mushrooms. The text is a collage of fragments: memories, dreams, dictionary definitions, journal entries, and quotations. The playful disregard for chronology and the variety of fonts, typefaces and sizes are a way of circumventing the feeling that grief has made words lose their meaning forever.

When Death Takes Something from You Give It Back: Carl’s Book by Naja Marie Aidt [137 pages]: In March 2015 Aidt got word that her son Carl Emil was dead. The 25-year-old jumped out of his fifth-floor Copenhagen window after taking some mushrooms. The text is a collage of fragments: memories, dreams, dictionary definitions, journal entries, and quotations. The playful disregard for chronology and the variety of fonts, typefaces and sizes are a way of circumventing the feeling that grief has made words lose their meaning forever.

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin [89 pages]: A hard-hitting book composed of two essays: “My Dungeon Shook,” is a letter addressed to his nephew and namesake on the 100th anniversary of emancipation; and “Down at the Cross: Letter from a Region in My Mind,” which first appeared in the New Yorker and tells of a crisis of faith that hit Baldwin when he was a teenager and started to question to what extent Christianity of all stripes was upholding white privilege. This feels completely relevant, and eminently quotable, nearly 60 years later.

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin [89 pages]: A hard-hitting book composed of two essays: “My Dungeon Shook,” is a letter addressed to his nephew and namesake on the 100th anniversary of emancipation; and “Down at the Cross: Letter from a Region in My Mind,” which first appeared in the New Yorker and tells of a crisis of faith that hit Baldwin when he was a teenager and started to question to what extent Christianity of all stripes was upholding white privilege. This feels completely relevant, and eminently quotable, nearly 60 years later.

Be My Guest: Reflections on Food, Community and the Meaning of Generosity by Priya Basil [117 pages]: A thought-provoking essay that reaches into many different topics. Part of an Indian family that has lived in Kenya and England, Basil is used to culinary abundance. However, living in Berlin increased her awareness of the suffering of the Other – hundreds of thousands of refugees have entered the EU to be met with hostility. Yet the Sikh tradition she grew up in teaches kindness to strangers. She asks how we can all cultivate a spirit of generosity.

Be My Guest: Reflections on Food, Community and the Meaning of Generosity by Priya Basil [117 pages]: A thought-provoking essay that reaches into many different topics. Part of an Indian family that has lived in Kenya and England, Basil is used to culinary abundance. However, living in Berlin increased her awareness of the suffering of the Other – hundreds of thousands of refugees have entered the EU to be met with hostility. Yet the Sikh tradition she grew up in teaches kindness to strangers. She asks how we can all cultivate a spirit of generosity.

Survival Lessons by Alice Hoffman [83 pages]: Hoffman wrote this 15 years after her own experience of breast cancer to encourage anyone going through a crisis. Each chapter title begins with the word “Choose” – a reminder that, even when you can’t choose your circumstances, you can choose your response. This has been beautifully put together with blue-tinted watercolor-effect photographs and an overall yellow and blue theme (along with deckle edge pages – a personal favorite book trait). It’s a sweet little memoir with a self-help note.

Survival Lessons by Alice Hoffman [83 pages]: Hoffman wrote this 15 years after her own experience of breast cancer to encourage anyone going through a crisis. Each chapter title begins with the word “Choose” – a reminder that, even when you can’t choose your circumstances, you can choose your response. This has been beautifully put together with blue-tinted watercolor-effect photographs and an overall yellow and blue theme (along with deckle edge pages – a personal favorite book trait). It’s a sweet little memoir with a self-help note.

A Sand County Almanac by Aldo Leopold [92 pages]: Few know how much of our current philosophy of wilderness and the human impact on the world is indebted to Aldo Leopold. This was published in 1949, but so much rings true today: how we only appreciate wildlife if we can put an economic value on it, the troubles we get into when we eradicate predators and let prey animals run rampant, and the danger of being disconnected from the land that supplies our very life. And all this he delivers in stunning, incisive prose.

A Sand County Almanac by Aldo Leopold [92 pages]: Few know how much of our current philosophy of wilderness and the human impact on the world is indebted to Aldo Leopold. This was published in 1949, but so much rings true today: how we only appreciate wildlife if we can put an economic value on it, the troubles we get into when we eradicate predators and let prey animals run rampant, and the danger of being disconnected from the land that supplies our very life. And all this he delivers in stunning, incisive prose.

The Communist Manifesto by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels [70 pages]: Maybe you, like me, had always assumed this was an impenetrable tome of hundreds of pages? But, as I discovered when I read it on the train to Manchester some years ago, it’s very compact. That’s not to say it’s an easy read; I’ve never been politically or economically minded, so I struggled to follow the argument at times. Mostly what I appreciated was the language. Like The Origin of Species, it has many familiar lines and wonderful metaphors.

The Communist Manifesto by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels [70 pages]: Maybe you, like me, had always assumed this was an impenetrable tome of hundreds of pages? But, as I discovered when I read it on the train to Manchester some years ago, it’s very compact. That’s not to say it’s an easy read; I’ve never been politically or economically minded, so I struggled to follow the argument at times. Mostly what I appreciated was the language. Like The Origin of Species, it has many familiar lines and wonderful metaphors.

Down and Out in Paris and London by George Orwell [189 pages]: Orwell’s first book, published when he was 30, is an excellent first-hand account of the working and living conditions of the poor in two world cities. He works as a dishwasher and waiter in Paris hotel restaurants for up to 80 hours a week and has to pawn his clothes to scrape together enough money to ward off starvation. Even as he’s conveying the harsh reality of exhaustion and indignity, Orwell takes a Dickensian delight in people and their eccentricities.

Down and Out in Paris and London by George Orwell [189 pages]: Orwell’s first book, published when he was 30, is an excellent first-hand account of the working and living conditions of the poor in two world cities. He works as a dishwasher and waiter in Paris hotel restaurants for up to 80 hours a week and has to pawn his clothes to scrape together enough money to ward off starvation. Even as he’s conveying the harsh reality of exhaustion and indignity, Orwell takes a Dickensian delight in people and their eccentricities.

Tiny Moons: A Year of Eating in Shanghai by Nina Mingya Powles [85 pages]: This lovely pamphlet of food-themed essays arose from a blog Powles kept while in Shanghai on a one-year scholarship to learn Mandarin. From one winter to another, she explores the city’s culinary offerings and muses on the ways in which food is bound up with her memories of people and places. This is about how food can help you be at home. I loved how she used the senses – not just taste, but also smell and sight – to recreate important places in her life.

Tiny Moons: A Year of Eating in Shanghai by Nina Mingya Powles [85 pages]: This lovely pamphlet of food-themed essays arose from a blog Powles kept while in Shanghai on a one-year scholarship to learn Mandarin. From one winter to another, she explores the city’s culinary offerings and muses on the ways in which food is bound up with her memories of people and places. This is about how food can help you be at home. I loved how she used the senses – not just taste, but also smell and sight – to recreate important places in her life.

The Living Mountain by Nan Shepherd [108 pages]: This is something of a lost nature classic. Composed during the later years of World War II but only published in 1977, it’s Shepherd’s tribute to her beloved Cairngorms, a mountain region of Scotland. But it’s not a travel or nature book in the way you might usually think of those genres. It’s a subtle, meditative, even mystical look at the forces of nature, which are majestic but also menacing. Shepherd dwells on the senses, the mountain flora and fauna, and the special quality of time and existence (what we’d today call mindfulness) achieved in a place of natural splendor and solitude.

The Living Mountain by Nan Shepherd [108 pages]: This is something of a lost nature classic. Composed during the later years of World War II but only published in 1977, it’s Shepherd’s tribute to her beloved Cairngorms, a mountain region of Scotland. But it’s not a travel or nature book in the way you might usually think of those genres. It’s a subtle, meditative, even mystical look at the forces of nature, which are majestic but also menacing. Shepherd dwells on the senses, the mountain flora and fauna, and the special quality of time and existence (what we’d today call mindfulness) achieved in a place of natural splendor and solitude.

Hope in the Dark: Untold Histories, Wild Possibilities by Rebecca Solnit [143 pages]: Solnit believes in the power of purposeful individuals working towards social justice, even in the face of dispiriting evidence (e.g. the largest protests the world had seen didn’t stop the Iraq War). Instead of perfectionism, she advises flexibility and resilience; things could be even worse had we not acted. Her strong and stirring writing is a reminder that, though injustice is always with us, so is everyday heroism.

Hope in the Dark: Untold Histories, Wild Possibilities by Rebecca Solnit [143 pages]: Solnit believes in the power of purposeful individuals working towards social justice, even in the face of dispiriting evidence (e.g. the largest protests the world had seen didn’t stop the Iraq War). Instead of perfectionism, she advises flexibility and resilience; things could be even worse had we not acted. Her strong and stirring writing is a reminder that, though injustice is always with us, so is everyday heroism.

Keep in touch via Twitter (@bookishbeck / @cathy746books) and Instagram (@bookishbeck / @cathy_746books). We’ll add any of your review links in to our master posts. Feel free to use the terrific feature image Cathy made and don’t forget the hashtag #NovNov.

The Emma Press has published poetry pamphlets before, but this is their inaugural full-length work. Rachel Spence’s second collection is in two parts: first is “Call & Response,” a sonnet sequence structured as a play and considering her relationship with her mother. Act 1 starts in 1976 and zooms forward to key moments when they fell out and then reversed their estrangement. The next section finds them in the new roles of patient and carer. “Your final check-up. August. Nimbus clouds / prised open by Delft blue. Waiting is hard.” In Act 3, death is near; “in that quantum hinge, we made / an alphabet from love’s ungrammared stutter.” The poems of the last act are dated precisely, not just to a month and year as earlier but down to the very day, hour and minute. Whether in Ludlow or Venice, Spence crystallizes moments from the ongoingness of grief, drawing images from the natural world.

The Emma Press has published poetry pamphlets before, but this is their inaugural full-length work. Rachel Spence’s second collection is in two parts: first is “Call & Response,” a sonnet sequence structured as a play and considering her relationship with her mother. Act 1 starts in 1976 and zooms forward to key moments when they fell out and then reversed their estrangement. The next section finds them in the new roles of patient and carer. “Your final check-up. August. Nimbus clouds / prised open by Delft blue. Waiting is hard.” In Act 3, death is near; “in that quantum hinge, we made / an alphabet from love’s ungrammared stutter.” The poems of the last act are dated precisely, not just to a month and year as earlier but down to the very day, hour and minute. Whether in Ludlow or Venice, Spence crystallizes moments from the ongoingness of grief, drawing images from the natural world. Not only the pun-tastic title, but also the excellent nominative determinism of chef and food historian Dr Neil Buttery’s name, earned this a place in my

Not only the pun-tastic title, but also the excellent nominative determinism of chef and food historian Dr Neil Buttery’s name, earned this a place in my  Foust’s fifth collection – at 41 pages, the length of a long chapbook – is in conversation with the language and storyline of 1984. George Orwell’s classic took on new prescience for her during Donald Trump’s first presidential term, a period marked by a pandemic as well as by corruption, doublespeak and violence. “Rally

Foust’s fifth collection – at 41 pages, the length of a long chapbook – is in conversation with the language and storyline of 1984. George Orwell’s classic took on new prescience for her during Donald Trump’s first presidential term, a period marked by a pandemic as well as by corruption, doublespeak and violence. “Rally

My last unread book by Ansell (whose

My last unread book by Ansell (whose  At a confluence of Southern, Black and gay identities, Kinard writes of matriarchal families, of congregations and choirs, of the descendants of enslavers and enslaved living side by side. The layout mattered more than I knew, reading an e-copy: often it is white text on a black page; words form rings or an infinity symbol; erasure poems gray out much of what has come before. “Boomerang” interludes imagine a chorus of fireflies offering commentary – just one of numerous insect metaphors. Mythology also plays a role. “A Tangle of Gorgons,” a sample poem I’d read before, wends its serpentine way across several pages. “Catalog of My Obsessions or Things I Answer to” presents an alphabetical list. For the most part, the poems were longer, wordier and more involved (four pages of notes on the style and allusions) than I tend to prefer, but I could appreciate the religious frame of reference and the alliteration.

At a confluence of Southern, Black and gay identities, Kinard writes of matriarchal families, of congregations and choirs, of the descendants of enslavers and enslaved living side by side. The layout mattered more than I knew, reading an e-copy: often it is white text on a black page; words form rings or an infinity symbol; erasure poems gray out much of what has come before. “Boomerang” interludes imagine a chorus of fireflies offering commentary – just one of numerous insect metaphors. Mythology also plays a role. “A Tangle of Gorgons,” a sample poem I’d read before, wends its serpentine way across several pages. “Catalog of My Obsessions or Things I Answer to” presents an alphabetical list. For the most part, the poems were longer, wordier and more involved (four pages of notes on the style and allusions) than I tend to prefer, but I could appreciate the religious frame of reference and the alliteration. “Immanuel was the centre of the world once. Long after it imploded, its gravitational pull remains.” McNaught grew up in an evangelical church in Winchester, England, but by the time he left for university he’d fallen away. Meanwhile, some peers left for Nigeria to become disciples at charismatic preacher TB Joshua’s Synagogue Church of All Nations in Lagos. It’s obvious to outsiders that this was a cult, but not so to those caught up in it. It took years and repeated allegations for people to wake up to faked healings, sexual abuse, and the ceding of control to a megalomaniac who got rich off of duping and exploiting followers. This book won the inaugural Fitzcarraldo Editions Essay Prize. I admired its blend of journalistic and confessional styles: research, interviews with friends and strangers alike, and reflection on the author’s own loss of faith. He gets to the heart of why people stayed: “A feeling of holding and of being held. A sense of fellowship and interdependence … the rare moments of transcendence … It was nice to be a superorganism.” This gripped me from page one, but its wider appeal strikes me as limited. For me, it was the perfect chance to think about how I might write about traditions I grew up in and spurned.

“Immanuel was the centre of the world once. Long after it imploded, its gravitational pull remains.” McNaught grew up in an evangelical church in Winchester, England, but by the time he left for university he’d fallen away. Meanwhile, some peers left for Nigeria to become disciples at charismatic preacher TB Joshua’s Synagogue Church of All Nations in Lagos. It’s obvious to outsiders that this was a cult, but not so to those caught up in it. It took years and repeated allegations for people to wake up to faked healings, sexual abuse, and the ceding of control to a megalomaniac who got rich off of duping and exploiting followers. This book won the inaugural Fitzcarraldo Editions Essay Prize. I admired its blend of journalistic and confessional styles: research, interviews with friends and strangers alike, and reflection on the author’s own loss of faith. He gets to the heart of why people stayed: “A feeling of holding and of being held. A sense of fellowship and interdependence … the rare moments of transcendence … It was nice to be a superorganism.” This gripped me from page one, but its wider appeal strikes me as limited. For me, it was the perfect chance to think about how I might write about traditions I grew up in and spurned. Like other short works I’ve read by Hispanic women authors (

Like other short works I’ve read by Hispanic women authors ( I knew from

I knew from  The epigraph is from the two pages of laughter (“Ha!”) in “Real Estate,” one of the stories of

The epigraph is from the two pages of laughter (“Ha!”) in “Real Estate,” one of the stories of

I’d read one memoir of working and living in Shakespeare and Company, Books, Baguettes and Bedbugs by Jeremy Mercer (original title: Time Was Soft There), back in 2017. I don’t remember it being particularly special as bookish memoirs go, but if you want an insider’s look at the bookshop that’s one option. Founder Sylvia Beach herself also wrote a memoir. The best part of any trip is preparing what books to take and read. I had had hardly any time to plan what else to pack, and ended up unprepared for the cold, but I had my shelf of potential reads ready weeks in advance. I took The Elegance of the Hedgehog by Muriel Barbery and read the first 88 pages before giving up. This story of several residents of the same apartment building, their families and sadness and thoughts, was reminiscent of

I’d read one memoir of working and living in Shakespeare and Company, Books, Baguettes and Bedbugs by Jeremy Mercer (original title: Time Was Soft There), back in 2017. I don’t remember it being particularly special as bookish memoirs go, but if you want an insider’s look at the bookshop that’s one option. Founder Sylvia Beach herself also wrote a memoir. The best part of any trip is preparing what books to take and read. I had had hardly any time to plan what else to pack, and ended up unprepared for the cold, but I had my shelf of potential reads ready weeks in advance. I took The Elegance of the Hedgehog by Muriel Barbery and read the first 88 pages before giving up. This story of several residents of the same apartment building, their families and sadness and thoughts, was reminiscent of  ):

): After a dinner party, Marji helps her grandmother serve tea from a samovar to their female family friends, and the eight Iranian women swap stories about their love lives. These are sometimes funny, but mostly sad and slightly shocking tales about arranged marriages, betrayals, and going to great lengths to entrap or keep a man. They range from a woman who has birthed four children but never seen a penis to a mistress who tried to use mild witchcraft to get a marriage proposal. What is most striking is how standards of beauty and purity have endured in this culture, leading women to despair over their loss of youth and virginity.

After a dinner party, Marji helps her grandmother serve tea from a samovar to their female family friends, and the eight Iranian women swap stories about their love lives. These are sometimes funny, but mostly sad and slightly shocking tales about arranged marriages, betrayals, and going to great lengths to entrap or keep a man. They range from a woman who has birthed four children but never seen a penis to a mistress who tried to use mild witchcraft to get a marriage proposal. What is most striking is how standards of beauty and purity have endured in this culture, leading women to despair over their loss of youth and virginity. We both read this, keeping two bookmarks in and trading it off on Metro journeys. The short thematic chapters, interspersed with recipes, were perfect for short bursts of reading, and the places and meals he described often presaged what we experienced. His observations on the French, too, rang true for us. Why no shower curtains? Why so much barging and cutting in line? Parisians are notoriously rude and selfish, and France’s bureaucracy is something I’ve read about in multiple places this year, including John Lewis-Stempel’s

We both read this, keeping two bookmarks in and trading it off on Metro journeys. The short thematic chapters, interspersed with recipes, were perfect for short bursts of reading, and the places and meals he described often presaged what we experienced. His observations on the French, too, rang true for us. Why no shower curtains? Why so much barging and cutting in line? Parisians are notoriously rude and selfish, and France’s bureaucracy is something I’ve read about in multiple places this year, including John Lewis-Stempel’s  This was consciously based on George Orwell’s

This was consciously based on George Orwell’s  I forgot to start it while I was there, but did soon afterwards: The Paris Novel by Ruth Reichl, forthcoming in early 2024. When Stella’s elegant, aloof mother Celia dies, she leaves her $8,000 – and instructions to go to Paris and not return to New York until she’s spent it all. At 2nd & Charles yesterday, I also picked up a clearance copy of A Paris All Your Own, an autobiographical essay collection edited by Eleanor Brown, to reread. I like to keep the spirit of a vacation alive a little longer, and books are one of the best ways to do that.

I forgot to start it while I was there, but did soon afterwards: The Paris Novel by Ruth Reichl, forthcoming in early 2024. When Stella’s elegant, aloof mother Celia dies, she leaves her $8,000 – and instructions to go to Paris and not return to New York until she’s spent it all. At 2nd & Charles yesterday, I also picked up a clearance copy of A Paris All Your Own, an autobiographical essay collection edited by Eleanor Brown, to reread. I like to keep the spirit of a vacation alive a little longer, and books are one of the best ways to do that.

This posthumous novella was written in the 1940s but never published in Brennan’s lifetime. From Dublin, she was a longtime New Yorker staff member and wrote acclaimed short stories. After her mother’s death, Anastasia King travels from Paris, where the two set up residence after leaving her father, to Ireland to stay in the family home with her grandmother. Anastasia considers it a return, a homecoming, but her spiteful grandmother makes it clear that she is an unwelcome interloper. Mrs King can’t forgive the wrong done to her son, and so won’t countenance Anastasia’s plan to repatriate her mother’s remains. Rejection and despair eat away at Anastasia’s mental health (“She saw the miserable gate of her defeat already open ahead. There only remained for her to come up to it and pass through it and be done with it”) but she pulls herself together for an act of defiance. Most affecting for me was a scene in which we learn that Anastasia is so absorbed in her own drama that she does not fulfill the simple last wish of a dying friend. This brought to mind James Joyce’s The Dead. (Secondhand purchase – The Bookshop, Wigtown) [81 pages]

This posthumous novella was written in the 1940s but never published in Brennan’s lifetime. From Dublin, she was a longtime New Yorker staff member and wrote acclaimed short stories. After her mother’s death, Anastasia King travels from Paris, where the two set up residence after leaving her father, to Ireland to stay in the family home with her grandmother. Anastasia considers it a return, a homecoming, but her spiteful grandmother makes it clear that she is an unwelcome interloper. Mrs King can’t forgive the wrong done to her son, and so won’t countenance Anastasia’s plan to repatriate her mother’s remains. Rejection and despair eat away at Anastasia’s mental health (“She saw the miserable gate of her defeat already open ahead. There only remained for her to come up to it and pass through it and be done with it”) but she pulls herself together for an act of defiance. Most affecting for me was a scene in which we learn that Anastasia is so absorbed in her own drama that she does not fulfill the simple last wish of a dying friend. This brought to mind James Joyce’s The Dead. (Secondhand purchase – The Bookshop, Wigtown) [81 pages]

If you’ve heard of this, it’ll be for the fact that the main character – Lou, a librarian sent to archive the holdings of an octagonal house on an island one summer – has sex with a bear. That makes it sound much more repulsive and/or titillating than it actually is. The further I read the more I started to think of it as an allegory for women’s awakening; perhaps the strategy inspired Melissa Broder’s

If you’ve heard of this, it’ll be for the fact that the main character – Lou, a librarian sent to archive the holdings of an octagonal house on an island one summer – has sex with a bear. That makes it sound much more repulsive and/or titillating than it actually is. The further I read the more I started to think of it as an allegory for women’s awakening; perhaps the strategy inspired Melissa Broder’s  Several of us reviewed this for #NovNov though unsure it counts: in the UK the title story (originally for the New Yorker) was published in a standalone volume by Faber, while the U.S. release includes two additional earlier stories; I read the latter. The title story has Cathal spending what should have been his wedding weekend moping about Sabine calling off their engagement at the last minute. It’s no mystery why she did: his misogyny, though not overt, runs deep, most evident in the terms in which he thinks about women. And where did he learn it? From his father. (“The Long and Painful Death” is from Keegan’s second collection, Walk the Blue Fields, and concerns a woman on a writing residency at an author’s historic house in Ireland. She makes a stand for her own work by refusing to cede place to an entitled male scholar. The final story is “Antarctica,” the lead story in that 1999 volume and a really terrific one I’d already experienced before. It’s as dark and surprising as an early Ian McEwan novel.) Keegan proves, as ever, to be a master at portraying emotions and relationships, but the one story is admittedly slight on its own, and its point obvious. (Read via Edelweiss) [64 pages]

Several of us reviewed this for #NovNov though unsure it counts: in the UK the title story (originally for the New Yorker) was published in a standalone volume by Faber, while the U.S. release includes two additional earlier stories; I read the latter. The title story has Cathal spending what should have been his wedding weekend moping about Sabine calling off their engagement at the last minute. It’s no mystery why she did: his misogyny, though not overt, runs deep, most evident in the terms in which he thinks about women. And where did he learn it? From his father. (“The Long and Painful Death” is from Keegan’s second collection, Walk the Blue Fields, and concerns a woman on a writing residency at an author’s historic house in Ireland. She makes a stand for her own work by refusing to cede place to an entitled male scholar. The final story is “Antarctica,” the lead story in that 1999 volume and a really terrific one I’d already experienced before. It’s as dark and surprising as an early Ian McEwan novel.) Keegan proves, as ever, to be a master at portraying emotions and relationships, but the one story is admittedly slight on its own, and its point obvious. (Read via Edelweiss) [64 pages]  “She is Europe’s eerie child, and she is part of the storm.” J.K. is a young woman who totes her typewriter around different European locations, sleeps with various boyfriends, hears strangers’ stories, and so on. Many of the people she meets are only designated by an initial. By contrast, the most fully realized character is her mother, Lillian Strauss. The chapters feel unconnected and the encounters within them random, building to nothing. Though a bit like

“She is Europe’s eerie child, and she is part of the storm.” J.K. is a young woman who totes her typewriter around different European locations, sleeps with various boyfriends, hears strangers’ stories, and so on. Many of the people she meets are only designated by an initial. By contrast, the most fully realized character is her mother, Lillian Strauss. The chapters feel unconnected and the encounters within them random, building to nothing. Though a bit like

Meier is a cemetery tour guide in Brooklyn, where she lives. She surveys American burial customs in particular, noting the lack of respect for Black and Native American burial grounds, the Civil War-era history of embalming, the increasing popularity of cremation, and the rise of garden cemeteries such as Mount Auburn in Cambridge, Massachusetts, which can serve as wildlife havens. The mass casualties and fear of infection associated with Covid-19 brought back memories of the AIDS epidemic, especially for those in New York City. Meier travels to a wide range of resting places, from potter’s fields for unclaimed bodies to the most manicured cemeteries. She also talks about newer options such as green burial, body composting, and the many memorial objects ashes can be turned into. I’m a dedicated reader of books about death and so found this fascinating, with the perfect respectful and just-shy-of-melancholy tone. It’s political and philosophical in equal measures. (Read via NetGalley) [168 pages]

Meier is a cemetery tour guide in Brooklyn, where she lives. She surveys American burial customs in particular, noting the lack of respect for Black and Native American burial grounds, the Civil War-era history of embalming, the increasing popularity of cremation, and the rise of garden cemeteries such as Mount Auburn in Cambridge, Massachusetts, which can serve as wildlife havens. The mass casualties and fear of infection associated with Covid-19 brought back memories of the AIDS epidemic, especially for those in New York City. Meier travels to a wide range of resting places, from potter’s fields for unclaimed bodies to the most manicured cemeteries. She also talks about newer options such as green burial, body composting, and the many memorial objects ashes can be turned into. I’m a dedicated reader of books about death and so found this fascinating, with the perfect respectful and just-shy-of-melancholy tone. It’s political and philosophical in equal measures. (Read via NetGalley) [168 pages]

Laboratory pregnancy tests have been available since the 1930s and home pregnancy tests – the focus here – since the 1970s. All of them work by testing urine for the hormone hCG (human chorionic gonadotropin). What is truly wild is that pregnancy used to be verifiable only with laboratory animals – female mice and rabbits had to be sacrificed to see if their ovaries had swelled after the injection of a woman’s urine; later, female Xenopus toads were found to lay eggs in response, so didn’t need to be killed. Home pregnancy kits were controversial and available in Canada before the USA because it was thought that they could be unreliable or that they would encourage early abortions. Weingarten brings together the history, laypeople-friendly science, and cultural representations (taking a pregnancy test is excellent TV shorthand) in a readable narrative and makes a clear feminist statement: “the home pregnancy test gave back to women what should have always been theirs: first-hand knowledge about how their bodies worked” and thus “had the potential to upend a paternalistic culture.” (Read via NetGalley) [160 pages]

Laboratory pregnancy tests have been available since the 1930s and home pregnancy tests – the focus here – since the 1970s. All of them work by testing urine for the hormone hCG (human chorionic gonadotropin). What is truly wild is that pregnancy used to be verifiable only with laboratory animals – female mice and rabbits had to be sacrificed to see if their ovaries had swelled after the injection of a woman’s urine; later, female Xenopus toads were found to lay eggs in response, so didn’t need to be killed. Home pregnancy kits were controversial and available in Canada before the USA because it was thought that they could be unreliable or that they would encourage early abortions. Weingarten brings together the history, laypeople-friendly science, and cultural representations (taking a pregnancy test is excellent TV shorthand) in a readable narrative and makes a clear feminist statement: “the home pregnancy test gave back to women what should have always been theirs: first-hand knowledge about how their bodies worked” and thus “had the potential to upend a paternalistic culture.” (Read via NetGalley) [160 pages]  The dc Talk album Jesus Freak (1995) is the first CD I ever owned. My best friend and I listened to it (along with Bloom by Audio Adrenaline and Take Me to Your Leader by Newsboys) so many times that we knew every word and note by heart. So it’s hard for me to be objective rather than nostalgic; I was intrigued to see what two secular academics would have to say. Crucially, they were teenage dc Talk fans, now ex-Evangelicals and homosexual partners. As English professors, their approach is to spot musical influences (Nirvana on the title track; R&B and gospel elsewhere), critically analyse lyrics (with “Colored People” proving problematic for its “neoliberal multiculturalism and its potential for post-racial utopianism”), and put a queer spin on things. For those who don’t know, dc Talk were essentially a boy band with three singers, one Black and two white – one of these a rapper. Stockton and Gilson chronicle the confusion of living with a same-sex attraction they couldn’t express as teens, and cheekily suggest there may have been something going on between dc Talk members Toby McKeehan and Michael Tait, who were roommates at Liberty University and apparently dismantled their bunk beds so they could sleep side by side. Hmmm! I was interested enough in the subject matter to overlook the humanities jargon. (Birthday gift from my wish list last year) [132 pages]

The dc Talk album Jesus Freak (1995) is the first CD I ever owned. My best friend and I listened to it (along with Bloom by Audio Adrenaline and Take Me to Your Leader by Newsboys) so many times that we knew every word and note by heart. So it’s hard for me to be objective rather than nostalgic; I was intrigued to see what two secular academics would have to say. Crucially, they were teenage dc Talk fans, now ex-Evangelicals and homosexual partners. As English professors, their approach is to spot musical influences (Nirvana on the title track; R&B and gospel elsewhere), critically analyse lyrics (with “Colored People” proving problematic for its “neoliberal multiculturalism and its potential for post-racial utopianism”), and put a queer spin on things. For those who don’t know, dc Talk were essentially a boy band with three singers, one Black and two white – one of these a rapper. Stockton and Gilson chronicle the confusion of living with a same-sex attraction they couldn’t express as teens, and cheekily suggest there may have been something going on between dc Talk members Toby McKeehan and Michael Tait, who were roommates at Liberty University and apparently dismantled their bunk beds so they could sleep side by side. Hmmm! I was interested enough in the subject matter to overlook the humanities jargon. (Birthday gift from my wish list last year) [132 pages]

Grumbach died last year at age 104. This was my third of her books; I read two previous memoirs,

Grumbach died last year at age 104. This was my third of her books; I read two previous memoirs,  It feels like I made an error by reading Levy’s “Living Autobiography,” out of order. I picked up the middle volume of the trilogy, The Cost of Living, for #NovNov in 2021 and it ended up being my favourite nonfiction read of that year. I then read part of the third book, Real Estate, last year but set it aside. And now I’ve read the first because it was the shortest. It’s loosely structured around George Orwell’s four reasons for writing: political purpose, historical impulse, sheer egoism and aesthetic enthusiasm. The frame story has her flying to Majorca at a time when she was struggling with her mental health. She vaguely follows in the footsteps of George Sand and then pauses to tell a Chinese shopkeeper the story of her upbringing in apartheid-era South Africa and the family’s move to London. Although I generally admire recreations of childhood and there are some strong pen portraits of minor characters, overall there was little that captivated me here and I was too aware of the writerly shaping. (Secondhand purchase – 2nd & Charles, Hagerstown) [111 pages]

It feels like I made an error by reading Levy’s “Living Autobiography,” out of order. I picked up the middle volume of the trilogy, The Cost of Living, for #NovNov in 2021 and it ended up being my favourite nonfiction read of that year. I then read part of the third book, Real Estate, last year but set it aside. And now I’ve read the first because it was the shortest. It’s loosely structured around George Orwell’s four reasons for writing: political purpose, historical impulse, sheer egoism and aesthetic enthusiasm. The frame story has her flying to Majorca at a time when she was struggling with her mental health. She vaguely follows in the footsteps of George Sand and then pauses to tell a Chinese shopkeeper the story of her upbringing in apartheid-era South Africa and the family’s move to London. Although I generally admire recreations of childhood and there are some strong pen portraits of minor characters, overall there was little that captivated me here and I was too aware of the writerly shaping. (Secondhand purchase – 2nd & Charles, Hagerstown) [111 pages]  I reviewed a couple of JLS’s species-specific monographs for #NovNov in 2018:

I reviewed a couple of JLS’s species-specific monographs for #NovNov in 2018:  I’ve read so many cancer stories that it takes a lot to make one stand out. This feels like a random collection of documents rather than a coherent memoir. One of the three essays was originally a speech, and two were previously printed in another of her books. Lorde was diagnosed with breast cancer in 1978 and had a mastectomy. A Black lesbian feminist, she resisted wearing prostheses and spoke up about the potential environmental causes of breast cancer that need to be addressed in research (“I may be a casualty in the cosmic war against radiation, animal fat, air pollution, McDonald’s hamburgers and Red Dye No. 2”). Her actual journal entries make up little of the text, which is for the best because fear and pain can bring out the cliches in us – but occasionally a great quote like “if bitterness were a whetstone, I could be sharp as grief.” Another favourite line: “Pain does not mellow you, nor does it ennoble, in my experience.” I’m keen to read her memoir Zami. (University library) [77 pages]

I’ve read so many cancer stories that it takes a lot to make one stand out. This feels like a random collection of documents rather than a coherent memoir. One of the three essays was originally a speech, and two were previously printed in another of her books. Lorde was diagnosed with breast cancer in 1978 and had a mastectomy. A Black lesbian feminist, she resisted wearing prostheses and spoke up about the potential environmental causes of breast cancer that need to be addressed in research (“I may be a casualty in the cosmic war against radiation, animal fat, air pollution, McDonald’s hamburgers and Red Dye No. 2”). Her actual journal entries make up little of the text, which is for the best because fear and pain can bring out the cliches in us – but occasionally a great quote like “if bitterness were a whetstone, I could be sharp as grief.” Another favourite line: “Pain does not mellow you, nor does it ennoble, in my experience.” I’m keen to read her memoir Zami. (University library) [77 pages]  I’d not read Matar before I spotted this art book-cum-memoir and thought, why not. A Libyan American novelist who lives in London, Matar had long been fascinated by the Sienese School of painting (13th to 15th centuries), many of whose artists depicted biblical scenes or religious allegories – even though he’s not a Christian. He spent a month in Italy immersed in the art he loves; there are 15 colour reproductions here. His explications of art history are generalist enough to be accessible to all readers, but I engaged more with the glimpses into his own life. For instance, he meets a fellow Arabic speaker and they quickly form a brotherly attachment, and a Paradise scene gives him fanciful hope of being reunited with his missing father – the subject of his Folio Prize-winning memoir The Return, which I’d like to read soon. His prose is beautiful as he reflects on history, death and how memories occupy ‘rooms’ in the imagination. A little more interest in the art would have helped, though. (Little Free Library) [118 pages]

I’d not read Matar before I spotted this art book-cum-memoir and thought, why not. A Libyan American novelist who lives in London, Matar had long been fascinated by the Sienese School of painting (13th to 15th centuries), many of whose artists depicted biblical scenes or religious allegories – even though he’s not a Christian. He spent a month in Italy immersed in the art he loves; there are 15 colour reproductions here. His explications of art history are generalist enough to be accessible to all readers, but I engaged more with the glimpses into his own life. For instance, he meets a fellow Arabic speaker and they quickly form a brotherly attachment, and a Paradise scene gives him fanciful hope of being reunited with his missing father – the subject of his Folio Prize-winning memoir The Return, which I’d like to read soon. His prose is beautiful as he reflects on history, death and how memories occupy ‘rooms’ in the imagination. A little more interest in the art would have helped, though. (Little Free Library) [118 pages]

I had high hopes for this childhood memoir that originally appeared in the New Yorker and was reprinted as part of the Canongate Classics series. But I soon resorted to skimming as her recollections of her shabby upper-class upbringing in a Highlands castle are full of page after page of description and dull recounting of events, with few scenes and little dialogue. This would be of high historical value for someone wanting to understand daily life for a certain fraction of society at the time, however. When Miller’s father died, she was only 10 and they had to leave the castle. I was intrigued to learn from her bio that she lived in Newbury for a time. (Secondhand purchase – Barter Books) [98 pages]

I had high hopes for this childhood memoir that originally appeared in the New Yorker and was reprinted as part of the Canongate Classics series. But I soon resorted to skimming as her recollections of her shabby upper-class upbringing in a Highlands castle are full of page after page of description and dull recounting of events, with few scenes and little dialogue. This would be of high historical value for someone wanting to understand daily life for a certain fraction of society at the time, however. When Miller’s father died, she was only 10 and they had to leave the castle. I was intrigued to learn from her bio that she lived in Newbury for a time. (Secondhand purchase – Barter Books) [98 pages]  This collection of micro-essays under themed headings like “Living in the Present” and “Suffering” was a perfect introduction to Nouwen’s life and theology. The Dutch Catholic priest lived in an Ontario community serving the physically and mentally disabled, and died of a heart attack just two years after this was published. I marked out many reassuring or thought-provoking passages. Here’s a good pre-Christmas one:

This collection of micro-essays under themed headings like “Living in the Present” and “Suffering” was a perfect introduction to Nouwen’s life and theology. The Dutch Catholic priest lived in an Ontario community serving the physically and mentally disabled, and died of a heart attack just two years after this was published. I marked out many reassuring or thought-provoking passages. Here’s a good pre-Christmas one:

My only reread for the month. Wilde wrote this from prison. No doubt he had a miserable time there, but keeping in mind that he was a flamboyant dramatist and had an eye to this being published someday, this time around I found it more exaggerated and self-pitying than I had before. “Suffering is one very long moment. … Where there is sorrow there is holy ground,” he writes, stating that he has found “harmony with the wounded, broken, and great heart of the world.” He says he’s not going to try to defend his behaviour … but what is this but one extended apologia and humble brag, likening himself to a Greek tragic hero (“The gods had given me almost everything. But I let myself be lured into long spells of senseless and sensual ease. I amused myself with being a flâneur, a dandy, a man of fashion”) and even to Christ in his individuality as well as in his suffering at the hands of those who don’t understand him (the scene where he was pilloried consciously mimics a crucifixion tableau). As a literary document, it’s extraordinary, but I didn’t buy his sincerity. He feigns remorse but, really, wasn’t sorry about anything, merely sorry he got caught. (Free from a neighbour) [151 pages]

My only reread for the month. Wilde wrote this from prison. No doubt he had a miserable time there, but keeping in mind that he was a flamboyant dramatist and had an eye to this being published someday, this time around I found it more exaggerated and self-pitying than I had before. “Suffering is one very long moment. … Where there is sorrow there is holy ground,” he writes, stating that he has found “harmony with the wounded, broken, and great heart of the world.” He says he’s not going to try to defend his behaviour … but what is this but one extended apologia and humble brag, likening himself to a Greek tragic hero (“The gods had given me almost everything. But I let myself be lured into long spells of senseless and sensual ease. I amused myself with being a flâneur, a dandy, a man of fashion”) and even to Christ in his individuality as well as in his suffering at the hands of those who don’t understand him (the scene where he was pilloried consciously mimics a crucifixion tableau). As a literary document, it’s extraordinary, but I didn’t buy his sincerity. He feigns remorse but, really, wasn’t sorry about anything, merely sorry he got caught. (Free from a neighbour) [151 pages] This comes out from Abrams Press in the USA on 8 November and I’ll be reviewing it for Shelf Awareness, so I’ll just give a few brief thoughts for now. Barba is a poet and senior editor for New York Review Books. She has collected pieces from a wide range of American literature, including essays, letters and early travel writings as well as poetry, which dominates.

This comes out from Abrams Press in the USA on 8 November and I’ll be reviewing it for Shelf Awareness, so I’ll just give a few brief thoughts for now. Barba is a poet and senior editor for New York Review Books. She has collected pieces from a wide range of American literature, including essays, letters and early travel writings as well as poetry, which dominates.

A good case of nominative determinism – the author’s name is pronounced “leaf” – and fun connections abound: during the course of his year-long odyssey, he spends time plant-hunting with Jon Dunn and Sophie Pavelle, whose books featured earlier in my flora-themed summer reading:

A good case of nominative determinism – the author’s name is pronounced “leaf” – and fun connections abound: during the course of his year-long odyssey, he spends time plant-hunting with Jon Dunn and Sophie Pavelle, whose books featured earlier in my flora-themed summer reading:  I was fascinated by the concept behind this one. “In the spring of 1936 a writer planted roses” is Solnit’s refrain; from there sprawls a book that’s somehow about everything: botany, geology, history, politics and war – as well as, of course, George Orwell’s life and works (with significant overlap with the

I was fascinated by the concept behind this one. “In the spring of 1936 a writer planted roses” is Solnit’s refrain; from there sprawls a book that’s somehow about everything: botany, geology, history, politics and war – as well as, of course, George Orwell’s life and works (with significant overlap with the