Three on a Theme: Christmas Novellas I (Re-)Read This Year

I wasn’t sure I’d manage any holiday-appropriate reading this year, but thanks to their novella length I actually finished three, two in advance and one in a single sitting on the day itself. Two of these happen to be in translation: little slices of continental Christmas.

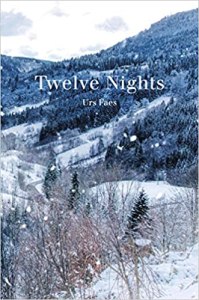

Twelve Nights by Urs Faes (2018; 2020)

[Translated from the German by Jamie Lee Searle]

In this Swiss novella, the Twelve Nights between Christmas and Epiphany are a time of mischief when good folk have to protect themselves from the tricks of evil spirits. Manfred has trekked back to his home valley hoping to make things right with his brother, Sebastian. They have been estranged for several decades – since Sebastian unexpectedly inherited the family farm and stole Manfred’s sweetheart, Minna. These perceived betrayals were met with a vengeful act of cruelty (but why oh why did it have to be against an animal?). At a snow-surrounded inn, Manfred convalesces and tries to summon the courage to show up at Sebastian’s door. At only 84 small-format pages, this is more of a short story. The setting and spare writing are appealing, as is the prospect of grace extended. But this was over before it began; it didn’t feel worth what I paid. Perhaps I would have been happier to encounter it in an anthology or a longer collection of Faes’s short fiction. (Secondhand – Hungerford Bookshop)

In this Swiss novella, the Twelve Nights between Christmas and Epiphany are a time of mischief when good folk have to protect themselves from the tricks of evil spirits. Manfred has trekked back to his home valley hoping to make things right with his brother, Sebastian. They have been estranged for several decades – since Sebastian unexpectedly inherited the family farm and stole Manfred’s sweetheart, Minna. These perceived betrayals were met with a vengeful act of cruelty (but why oh why did it have to be against an animal?). At a snow-surrounded inn, Manfred convalesces and tries to summon the courage to show up at Sebastian’s door. At only 84 small-format pages, this is more of a short story. The setting and spare writing are appealing, as is the prospect of grace extended. But this was over before it began; it didn’t feel worth what I paid. Perhaps I would have been happier to encounter it in an anthology or a longer collection of Faes’s short fiction. (Secondhand – Hungerford Bookshop) ![]()

Through a Glass, Darkly by Jostein Gaarder (1993; 1998)

[Translated from the Norwegian by Elizabeth Rokkan]

On Christmas Day, Cecilia is mostly confined to bed, yet the preteen experiences the holiday through the sounds and smells of what’s happening downstairs. (What a cosy first page!)

Her father later carries her down to open her presents: skis, a toboggan, skates – her family has given her all she asked for even though everyone knows she won’t be doing sport again; there is no further treatment for her terminal cancer. That night, the angel Ariel appears to Cecilia and gets her thinking about the mysteries of life. He’s fascinated by memory and the temporary loss of consciousness that is sleep. How do these human processes work? “I wish I’d thought more about how it is to live,” Cecilia sighs, to which Ariel replies, “It’s never too late.” Weeks pass and Ariel engages Cecilia in dialogues and takes her on middle-of-the-night outdoor adventures, always getting her back before her parents get up to check on her. The book emphasizes the wonder of being alive: “You are an animal with the soul of an angel, Cecilia. In that way you’ve been given the best of both worlds.” This is very much a YA book and a little saccharine for me, but at least it was only 161 pages rather than the nearly 400 of Sophie’s World. (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project, Newbury)

Her father later carries her down to open her presents: skis, a toboggan, skates – her family has given her all she asked for even though everyone knows she won’t be doing sport again; there is no further treatment for her terminal cancer. That night, the angel Ariel appears to Cecilia and gets her thinking about the mysteries of life. He’s fascinated by memory and the temporary loss of consciousness that is sleep. How do these human processes work? “I wish I’d thought more about how it is to live,” Cecilia sighs, to which Ariel replies, “It’s never too late.” Weeks pass and Ariel engages Cecilia in dialogues and takes her on middle-of-the-night outdoor adventures, always getting her back before her parents get up to check on her. The book emphasizes the wonder of being alive: “You are an animal with the soul of an angel, Cecilia. In that way you’ve been given the best of both worlds.” This is very much a YA book and a little saccharine for me, but at least it was only 161 pages rather than the nearly 400 of Sophie’s World. (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project, Newbury) ![]()

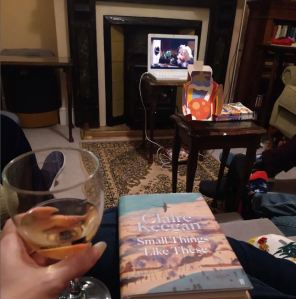

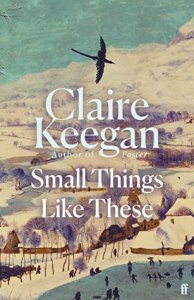

Small Things Like These by Claire Keegan (2021)

I idly reread this while The Muppet Christmas Carol played in the background on a lazy, overfed Christmas evening.

It was an odd experience: having seen the big-screen adaptation just last month, the blow-by-blow was overly familiar to me and I saw Cillian Murphy and Emily Watson, if not the minor actors, in my mind’s eye. I realized fully just how faithful the screenplay is to the book. The film enhances not just the atmosphere but also the plot through the visuals. It takes what was so subtle in the book – blink-and-you’ll-miss-it – and makes it more obvious. Normally I might think it a shame to undermine the nuance, but in this case I was glad of it. Bill Furlong’s midlife angst and emotional journey, in particular, are emphasized in the film. It was probably a mistake to read this a third time within so short a span of time; it often takes me more like 5–10 years to appreciate a book anew. So I was back to my ‘nice little story’ reaction this time, but would still recommend this to you – book or film – if you haven’t yet experienced it. (Free at a West Berkshire Council recycling event)

It was an odd experience: having seen the big-screen adaptation just last month, the blow-by-blow was overly familiar to me and I saw Cillian Murphy and Emily Watson, if not the minor actors, in my mind’s eye. I realized fully just how faithful the screenplay is to the book. The film enhances not just the atmosphere but also the plot through the visuals. It takes what was so subtle in the book – blink-and-you’ll-miss-it – and makes it more obvious. Normally I might think it a shame to undermine the nuance, but in this case I was glad of it. Bill Furlong’s midlife angst and emotional journey, in particular, are emphasized in the film. It was probably a mistake to read this a third time within so short a span of time; it often takes me more like 5–10 years to appreciate a book anew. So I was back to my ‘nice little story’ reaction this time, but would still recommend this to you – book or film – if you haven’t yet experienced it. (Free at a West Berkshire Council recycling event)

Previous ratings: ![]() (2021 review);

(2021 review); ![]() (2022 review)

(2022 review)

My rating this time: ![]()

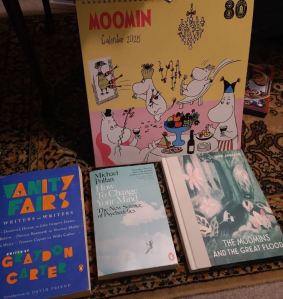

We hosted family for Christmas for the first time, which truly made me feel like a proper grown-up. It was stressful and chaotic but lovely and over all too soon. Here’s my lil’ book haul (but there was also a £50 book token, so I will buy many more!).

I hope everyone has been enjoying the holidays. I have various year-end posts in progress but of course the final Best-of list and statistics will have to wait until the turning of the year.

Coming up:

Sunday 29th: Best Backlist Reads of the Year

Monday 30th: Love Your Library & 2024 Reading Superlatives

Tuesday 31st: Best Books of 2024

Wednesday 1st: Final statistics on 2024’s reading

#NovNov24 and #GermanLitMonth: Knulp by Hermann Hesse (1915)

My second contribution to German Literature Month (hosted by Lizzy Siddal) after A Simple Intervention by Yael Inokai. This was my first time reading the German-Swiss Nobel Prize winner Hermann Hesse (1877–1962). I had heard of his novels Siddhartha and Steppenwolf, of course, but didn’t know about any of his shorter works before I picked this up from the Little Free Library last month. Knulp is a novella in three stories that provide complementary angles on the title character, a carefree vagabond whose rambling years are coming to an end.

“Early Spring” has a first-person plural narrator, opening “Once, early in the nineties, our friend Knulp had to go to hospital for several weeks.” Upon his discharge he stays with an old friend, the tanner Rothfuss, and spends his time visiting other local tradespeople and casually courting a servant girl. Knulp is a troubadour, writing poems and songs. Without career, family, or home, he lives in childlike simplicity.

He had seldom been arrested and never convicted of theft or mendicancy, and he had highly respected friends everywhere. Consequently, he was indulged by the authorities very much, as a nice-looking cat is indulged in a household, and left free to carry on an untroubled, elegant, splendidly aristocratic and idle existence.

“My Recollections of Knulp” is narrated by a friend who joined him as a tramp for a few weeks one midsummer. It wasn’t all music and jollity; Knulp also pondered the essential loneliness of the human condition in view of mortality. “His conversation was often heavy with philosophy, but his songs had the lightness of children playing in their summer clothes.”

“My Recollections of Knulp” is narrated by a friend who joined him as a tramp for a few weeks one midsummer. It wasn’t all music and jollity; Knulp also pondered the essential loneliness of the human condition in view of mortality. “His conversation was often heavy with philosophy, but his songs had the lightness of children playing in their summer clothes.”

In “The End,” Knulp encounters another school friend, Dr. Machold, who insists on sheltering the wayfarer. They’re in their forties but Knulp seems much older because he is ill with tuberculosis. As winter draws in, he resists returning to the hospital, wanting to die as he lived, on his own terms. The book closes with an extraordinary passage in which Knulp converses with God – or his hallucination of such – expressing his regret that he never made more of his talents or had a family. ‘God’ speaks these beautiful words of reassurance:

Look, I wanted you the way you are and no different. You were a wanderer in my name and wherever you went you brought the settled folk a little homesickness for freedom. In my name, you did silly things and people scoffed at you; I myself was scoffed at in you and loved in you. You are my child and my brother and a part of me. There is nothing you have enjoyed and suffered that I have not enjoyed and suffered with you.

I struggle with episodic fiction but have a lot of time for the theme of spiritual questioning. The seasons advance across the stories so that Knulp’s course mirrors the year’s. Knulp could almost be a rehearsal for Stoner: a spare story of the life and death of an Everyman. That I didn’t appreciate it more I put down to the piecemeal nature of the narrative and an unpleasant conversation between Knulp and Machold about adolescent sexual experiences – as in the attempted gang rape scene in Cider with Rosie, it’s presented as boyish fun when part of what Knulp recalls is actually molestation by an older girl cousin. I might be willing to try something else by Hesse. Do give me recommendations! (Little Free Library) ![]()

Translated from the German by Ralph Manheim.

[125 pages]

Mini playlist:

- “Ramblin’ Man” by Lemon Jelly

- “I’ve Been Everywhere” by Johnny Cash

- “Rambling Man” by Laura Marling

- “Ballad of a Broken Man” by Duke Special

- “Railroad Man” by Eels

I have also recently read a 2025 release that counts towards these challenges, The Café with No Name by Robert Seethaler (Europa Editions; translated by Katy Derbyshire; 192 pages). The protagonist, Robert Simon [Robert S., eh? Coincidence?], is not unlike Knulp, though less blithe, or the unassuming Bob Burgess from Elizabeth Strout’s novels (e.g., Tell Me Everything). Robert takes over the market café in Vienna and over the next decade or so his establishment becomes a haven for the troubled. The Second World War still looms large, and disasters large and small unfold. It’s all rather melancholy; I admired the chapters that turn the customers’ conversation into a swirling chorus. In my review, pending for Foreword Reviews, I call it “a valedictory meditation on the passage of time and the bonds that last.”

I have also recently read a 2025 release that counts towards these challenges, The Café with No Name by Robert Seethaler (Europa Editions; translated by Katy Derbyshire; 192 pages). The protagonist, Robert Simon [Robert S., eh? Coincidence?], is not unlike Knulp, though less blithe, or the unassuming Bob Burgess from Elizabeth Strout’s novels (e.g., Tell Me Everything). Robert takes over the market café in Vienna and over the next decade or so his establishment becomes a haven for the troubled. The Second World War still looms large, and disasters large and small unfold. It’s all rather melancholy; I admired the chapters that turn the customers’ conversation into a swirling chorus. In my review, pending for Foreword Reviews, I call it “a valedictory meditation on the passage of time and the bonds that last.”

#MoominWeek & #WITMonth, II: Moominpappa at Sea by Tove Jansson

My first two reads for Women in Translation month were Catalan and French novellas. With this third one I’m tying in with Moomin Week, hosted by Chris and Mallika in honour of Paula of Book Jotter. Happy nuptials to Paula! Not a blogger I’ve interacted with before, but I welcomed the excuse to finish a book I started a few months ago. I’ve actually reviewed five Moomin books here before: Moominvalley in November, Moominland Midwinter, Tales from Moominvalley, Moominsummer Madness, and Finn Family Moomintroll. (It’s also the third year in a row that I’ve reviewed something by Jansson for WIT Month.)

Appropriate reading at sea (on a ferry to France)

I didn’t grow up with the Moomins, but as an adult I’ve come to love the series for how it lovingly depicts everyday disasters and neuroses and, beneath the whimsical adventures, offers an extra level of thoughtfulness for adult readers. The setting of this one was particularly appropriate. Here’s the opening paragraph:

One afternoon at the end of August, Moominpappa was walking about in his garden feeling at a loss. He had no idea what to do with himself, because it seemed everything there was to be done had already been done or was being done by somebody else.

The sense of being ‘all at sea’ persists for Pappa and the other characters even after they sail to ‘his’ island in the Gulf of Finland, drawn to see in person the lighthouse he has kept as a model on the shelf. They arrive to find the island mysteriously empty and the facilities derelict. Moomintroll goes exploring alone and meets intriguing “sea-horses” that look more equine than marine. Nature is alive and resistant to ‘improvements’ such as Moominmamma trying to tame the wildness with her rose bushes and apple trees. The forest also seems to be retreating from the sea; everything fears it, in fact. The sullen fisherman is no help, and the hulking Groke seems to be a metaphor for depression as well as a literal monster.

The sense of being ‘all at sea’ persists for Pappa and the other characters even after they sail to ‘his’ island in the Gulf of Finland, drawn to see in person the lighthouse he has kept as a model on the shelf. They arrive to find the island mysteriously empty and the facilities derelict. Moomintroll goes exploring alone and meets intriguing “sea-horses” that look more equine than marine. Nature is alive and resistant to ‘improvements’ such as Moominmamma trying to tame the wildness with her rose bushes and apple trees. The forest also seems to be retreating from the sea; everything fears it, in fact. The sullen fisherman is no help, and the hulking Groke seems to be a metaphor for depression as well as a literal monster.

There is a sense of everything being awry, and by the close that’s only partially rectified. Pappa ends with conflicting feelings towards the island: proprietary yet timorous. I imagine this is based on Jansson’s own experiences living on a Finnish island (see also The Summer Book). This wasn’t among my favourite Moomin books, but I always appreciate the juxtaposition of the domestic and wild, the cosy and the melancholy. Just two more for me to find now (I’ve read them all in random order): The Moomins and the Great Flood and Moominpappa’s Memoirs.

[Translated from the Swedish by Kingsley Hart] (University library) ![]()

Summery Reading, Part I: Heatwave, Summer Fridays

Here we are between short, bearable heat waves. As the climate changes, I’m more grateful than ever to live somewhere with reasonably mild and predictable weather; I don’t miss the swampy humidity of the Maryland summers I grew up with one bit. Today I have some brief thoughts on a first pair of summer-themed reads I picked up last month: a queasy coming-of-age novella about French teenagers’ self-destructive actions on a camping holiday; and a fun, nostalgic romance novel set in New York City at the turn of the millennium.

Heatwave by Victor Jestin (2019; 2021)

[Translated from the French by Sam Taylor]

Victor Jestin was in his early twenties when he wrote this debut novella, which won the Prix Femina des Lycéens and was longlisted for the CWA Crime Fiction in Translation Dagger. It opens, memorably, with Leonard’s confession: “Oscar is dead because I watched him die and did nothing. He was strangled by the ropes of a swing … Oscar was not a child. At seventeen, you don’t die like that by accident.” A suicide, then: fitting given the other dangerous behaviours – drinking and promiscuity – rife among the gang of teenagers at this campsite in the South of France. What turns it into a crime is that Leonard, addled by alcohol and the heat, doesn’t report the death but buries Oscar in the sand and pretends nothing happened.

Victor Jestin was in his early twenties when he wrote this debut novella, which won the Prix Femina des Lycéens and was longlisted for the CWA Crime Fiction in Translation Dagger. It opens, memorably, with Leonard’s confession: “Oscar is dead because I watched him die and did nothing. He was strangled by the ropes of a swing … Oscar was not a child. At seventeen, you don’t die like that by accident.” A suicide, then: fitting given the other dangerous behaviours – drinking and promiscuity – rife among the gang of teenagers at this campsite in the South of France. What turns it into a crime is that Leonard, addled by alcohol and the heat, doesn’t report the death but buries Oscar in the sand and pretends nothing happened.

The rest of the book takes place over about 24 hours, the final day of a two-week vacation. Leo stumbles about as if in a trance, outwardly relating to his family, a male friend who seems to have a crush on him, and girls he’d like to sleep with, but all the while inwardly wondering what to do next. “I hadn’t made many stupid mistakes in my seventeen years of life. This one was difficult to understand. It all happened too fast; I felt powerless.” This is interesting enough if you like unreliable teenage narrators or are drawn by the critics’ comparisons to Françoise Sagan – accurate for the sense of sleepwalking toward disaster. One could easily breeze through the 104 pages during one hot afternoon. It didn’t stand out to me particularly, though. (Little Free Library) ![]()

Summer Fridays by Suzanne Rindell (2024)

I was a big fan of Rindell’s first two stylish historical novels, The Other Typist and Three-Martini Lunch. She seemed to go off the boil with the next two, which I skipped, and now she’s back with an unexpected foray into romance, a genre I almost never read. The cover’s whimsical (nonexistent) birds and Ryan Gosling-like male figure make the novel seem frothier than it actually is, though we’re definitely in classic romcom territory here. The comparisons to You’ve Got Mail are apt in that the main character, Sawyer, strikes up a flirtation over e-mail and instant messaging. She’s a New York City publishing assistant whose ambitions threaten her day job when she has several poems accepted by The Paris Review. Nick, her correspondent, teases and cheers her on in equal measure. The complicated thing is that Sawyer is engaged to Charles, her college sweetheart, and Nick is dating Kendra. Nick and Sawyer initially became digital pen pals because they suspected that their partners, who work together at a law firm, were having an affair; they never expected sparks to fly.

I was a big fan of Rindell’s first two stylish historical novels, The Other Typist and Three-Martini Lunch. She seemed to go off the boil with the next two, which I skipped, and now she’s back with an unexpected foray into romance, a genre I almost never read. The cover’s whimsical (nonexistent) birds and Ryan Gosling-like male figure make the novel seem frothier than it actually is, though we’re definitely in classic romcom territory here. The comparisons to You’ve Got Mail are apt in that the main character, Sawyer, strikes up a flirtation over e-mail and instant messaging. She’s a New York City publishing assistant whose ambitions threaten her day job when she has several poems accepted by The Paris Review. Nick, her correspondent, teases and cheers her on in equal measure. The complicated thing is that Sawyer is engaged to Charles, her college sweetheart, and Nick is dating Kendra. Nick and Sawyer initially became digital pen pals because they suspected that their partners, who work together at a law firm, were having an affair; they never expected sparks to fly.

It’s overlong and reasonably predictable, but I enjoyed the languid unfolding of the romance over the weeks of summer 1999. It was truly a simpler time when you had to dial up and wait for an inbox to load instead of having it in your pocket 24/7. Every Friday afternoon, Sawyer and Nick do touristy things like taste-test hotdogs and slushees, ride the Staten Island ferry back and forth all day, and visit little-known bars and restaurants Nick knows through his amateur rock band. They try to convince themselves that these are not dates. It’s like time outside of time for them, and a chance to sightsee in one’s own town. Eventually, though, Sawyer has to face reality. The 2001 framing story reflects the fact that, after the events of 9/11, many asked themselves what they really wanted out of life. This was cute but doesn’t quite live up to, e.g., Romantic Comedy. (Read via Edelweiss) ![]()

Any “heat” or “summer” books for you this year?

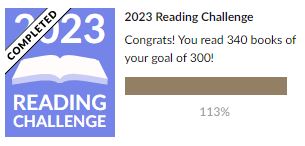

Final Reading Statistics for 2023

In 2022 my reading total dipped to 300, whereas in 2023 I was back up to what seems to be my natural limit of 340 books (as 2019–21 also proved).

The statistics

Fiction: 52.1%

Nonfiction: 31.2%

Poetry: 16.8%

(Poetry is up by nearly 3% and fiction and nonfiction down by a percent or so each compared to last year. I attribute this to specializing in poetry reviews for Shelf Awareness.)

Female author: 69.7%

Male author: 27.6%

Nonbinary author: 2.1%

Multiple genders (anthologies): 0.6%

(I always read more from women than from men, but was surprised to see that the percentage by men rose by 4.6% last year.)

BIPOC author: 22.4%

(The third time I have specifically tracked this figure. I’m pleased that it’s increased year on year: 18.5%, then 20.7%. I will continue to aim at 25% or more.)

LGBTQ: 18.2%

(This is a new category for me. I define it by the identity of the author and/or a major theme in the work; just having a secondary character who is gay wouldn’t count. I retrospectively looked at 2021 and 2022, which would have been at 11.8% and 8.8%.)

Work in translation: 10.6%!

(I’m delighted with this figure because the past two years were at just 5% and 8.7% and my aim was to be close to 10%. Most popular languages: Spanish (10), French (9) and Swedish (4); German (3), Italian (3), Danish (2), Dutch (2), Korean (1), Polish (1) and Welsh (1) were also represented.)

Backlist: 55.3%

2023 (or 2024 pre-release) books: 44.7%

(This is not too bad, although 17.9% of the ‘backlist’ stuff was from 2021 or 2022, so fairly recent releases I was catching up on from review copies, the library or in e-book form. My oldest reads were both from 1897, Liza of Lambeth by W. Somerset Maugham and De Profundis by Oscar Wilde.)

E-books: 27.4%

Print books: 72.6%

(On par with last year. I almost exclusively read e-books for BookBrowse, Foreword and Shelf Awareness reviews.)

Rereads: 9

(Compared to 12 each of the past two years; at least one per month would be a good aim.)

Where my books came from for the whole year, compared to last year:

- Free print or e-copy from publisher: 43.5% (↑1.5%)

- Public library: 24.1% (↓5.9%)

- Secondhand purchase: 10% (↑3.3%)

- Downloaded from NetGalley or Edelweiss: 6.8% (↓0.2%)

- Free (giveaways, Little Free Library/free bookshop, from friends or neighbours): 5.9% (↑3.3%)

- Gifts: 4.1% (↑0.1%)

- University library: 3.2% (↑0.9%)

- New purchase (often at a bargain price): 2.1% (↓2.6%)

- Borrowed: 0.3% (↓0.4%)

So nearly a quarter of my reading (22.1%) was from my own shelves. I’d like to make it more like 33–50%, achieved by a drop in review copies rather than library borrowing.

Additional statistics courtesy of Goodreads:

73,861 pages read

Average book length: 217 pages (down from 225 last year; thank you, novellas and poetry)

Average rating for 2022: 3.6 (identical to last year)

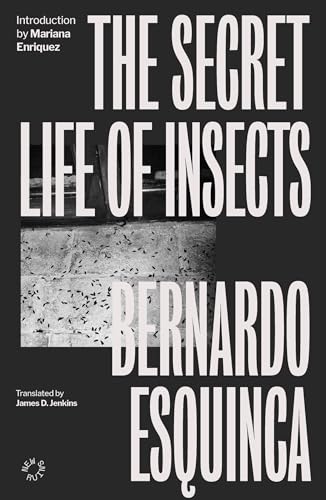

Mysterious manuscripts and therapy appointments also recur – there’s a scholarly Freudianism at play here. In the novella-length “Demoness,” friends at a twentieth high school reunion recount traumatic experiences from adolescence (not your average campfire fare). “Our traumas define us much more than our happy moments, [Ignacio, a Jesuit priest] thought. They’re the real revelations about ourselves.” Masturbation features heavily in this and in “Pan’s Noontide,” which has both of Arturo’s wives disappear in connection with an ecoterrorism cult. I occasionally found the content a bit macho and gross-out, and wished the women could be more than just sexualized supporting figures in male fantasies.

Mysterious manuscripts and therapy appointments also recur – there’s a scholarly Freudianism at play here. In the novella-length “Demoness,” friends at a twentieth high school reunion recount traumatic experiences from adolescence (not your average campfire fare). “Our traumas define us much more than our happy moments, [Ignacio, a Jesuit priest] thought. They’re the real revelations about ourselves.” Masturbation features heavily in this and in “Pan’s Noontide,” which has both of Arturo’s wives disappear in connection with an ecoterrorism cult. I occasionally found the content a bit macho and gross-out, and wished the women could be more than just sexualized supporting figures in male fantasies.

I’d been vaguely attracted by descriptions of the Spanish poet’s novels Permafrost and Boulder, which are also about lesbians in odd situations. Mammoth is the third book in a loose trilogy. Its 24-year-old narrator is so desperate for a baby that she’s decided to have unprotected sex with men until a pregnancy results. In the meantime, her sociology project at nursing homes comes to an end and she moves from Barcelona to a remote farm where she develops subsistence skills and forms an interdependent relationship with the gruff shepherd. “I’d been living in a drowning city, and I need this – the restorative silence of a decompression chamber. … my past is meaningless, and yet here, in this place, there is someone else’s past that I can set up and live in awhile.” For me this was a peculiar combination of distinguished writing (“The city pounces on the still-pale light emerging from the deep sea and seizes it with its lucrative forceps”) but absolutely repellent story, with a protagonist whose every decision makes you want to throttle her. An extended scene of exterminating feral cats certainly didn’t help matters. I’d be wary of trying Baltasar again.

I’d been vaguely attracted by descriptions of the Spanish poet’s novels Permafrost and Boulder, which are also about lesbians in odd situations. Mammoth is the third book in a loose trilogy. Its 24-year-old narrator is so desperate for a baby that she’s decided to have unprotected sex with men until a pregnancy results. In the meantime, her sociology project at nursing homes comes to an end and she moves from Barcelona to a remote farm where she develops subsistence skills and forms an interdependent relationship with the gruff shepherd. “I’d been living in a drowning city, and I need this – the restorative silence of a decompression chamber. … my past is meaningless, and yet here, in this place, there is someone else’s past that I can set up and live in awhile.” For me this was a peculiar combination of distinguished writing (“The city pounces on the still-pale light emerging from the deep sea and seizes it with its lucrative forceps”) but absolutely repellent story, with a protagonist whose every decision makes you want to throttle her. An extended scene of exterminating feral cats certainly didn’t help matters. I’d be wary of trying Baltasar again. At age 39, divorced interior decorator Paule is “passionately concerned with her beauty and battling with the transition from young to youngish woman”. (Ouch. But true.) It’s an open secret that her partner Roger is always engaged in a liaison with a young woman; people pity her and scorn Roger for his infidelity. But when Paule has a dalliance with a client’s son, 25-year-old lawyer Simon, a double standard emerges: “they had never shown her the mixture of contempt and envy she was going to arouse this time.” Simon is an idealist, accusing her of “letting love go by, of neglecting your duty to be happy”, but he’s also indolent and too fond of drink. Paule wonders if she’s expected too much from an affair. “Everyone advised a change of air, and she thought sadly that all she was getting was a change of lovers: less bother, more Parisian, so common”.

At age 39, divorced interior decorator Paule is “passionately concerned with her beauty and battling with the transition from young to youngish woman”. (Ouch. But true.) It’s an open secret that her partner Roger is always engaged in a liaison with a young woman; people pity her and scorn Roger for his infidelity. But when Paule has a dalliance with a client’s son, 25-year-old lawyer Simon, a double standard emerges: “they had never shown her the mixture of contempt and envy she was going to arouse this time.” Simon is an idealist, accusing her of “letting love go by, of neglecting your duty to be happy”, but he’s also indolent and too fond of drink. Paule wonders if she’s expected too much from an affair. “Everyone advised a change of air, and she thought sadly that all she was getting was a change of lovers: less bother, more Parisian, so common”.

Cyrus Shams is an Iranian American aspiring poet who grew up in Indiana with a single father, his mother Roya having died in a passenger aircraft mistakenly shot down by a U.S. Navy missile cruiser (this really happened: Iran Air Flight 655, on 3 July 1988). He continues to lurk around the Keady University campus, working as a medical actor at the hospital, but his ambition is to write. During his shaky recovery from drug and alcohol abuse, he undertakes a project that seems divinely inspired: “Tired of interventionist pyrotechnics like burning bushes and locust plagues, maybe God now worked through the tired eyes of drunk Iranians in the American Midwest”. By seeking the meaning in others’ deaths, he hopes his modern “Book of Martyrs” will teach him how to cherish his own life.

Cyrus Shams is an Iranian American aspiring poet who grew up in Indiana with a single father, his mother Roya having died in a passenger aircraft mistakenly shot down by a U.S. Navy missile cruiser (this really happened: Iran Air Flight 655, on 3 July 1988). He continues to lurk around the Keady University campus, working as a medical actor at the hospital, but his ambition is to write. During his shaky recovery from drug and alcohol abuse, he undertakes a project that seems divinely inspired: “Tired of interventionist pyrotechnics like burning bushes and locust plagues, maybe God now worked through the tired eyes of drunk Iranians in the American Midwest”. By seeking the meaning in others’ deaths, he hopes his modern “Book of Martyrs” will teach him how to cherish his own life.

This is the third C-PTSD memoir I’ve read (after

This is the third C-PTSD memoir I’ve read (after

My last unread book by Ansell (whose

My last unread book by Ansell (whose  At a confluence of Southern, Black and gay identities, Kinard writes of matriarchal families, of congregations and choirs, of the descendants of enslavers and enslaved living side by side. The layout mattered more than I knew, reading an e-copy: often it is white text on a black page; words form rings or an infinity symbol; erasure poems gray out much of what has come before. “Boomerang” interludes imagine a chorus of fireflies offering commentary – just one of numerous insect metaphors. Mythology also plays a role. “A Tangle of Gorgons,” a sample poem I’d read before, wends its serpentine way across several pages. “Catalog of My Obsessions or Things I Answer to” presents an alphabetical list. For the most part, the poems were longer, wordier and more involved (four pages of notes on the style and allusions) than I tend to prefer, but I could appreciate the religious frame of reference and the alliteration.

At a confluence of Southern, Black and gay identities, Kinard writes of matriarchal families, of congregations and choirs, of the descendants of enslavers and enslaved living side by side. The layout mattered more than I knew, reading an e-copy: often it is white text on a black page; words form rings or an infinity symbol; erasure poems gray out much of what has come before. “Boomerang” interludes imagine a chorus of fireflies offering commentary – just one of numerous insect metaphors. Mythology also plays a role. “A Tangle of Gorgons,” a sample poem I’d read before, wends its serpentine way across several pages. “Catalog of My Obsessions or Things I Answer to” presents an alphabetical list. For the most part, the poems were longer, wordier and more involved (four pages of notes on the style and allusions) than I tend to prefer, but I could appreciate the religious frame of reference and the alliteration. “Immanuel was the centre of the world once. Long after it imploded, its gravitational pull remains.” McNaught grew up in an evangelical church in Winchester, England, but by the time he left for university he’d fallen away. Meanwhile, some peers left for Nigeria to become disciples at charismatic preacher TB Joshua’s Synagogue Church of All Nations in Lagos. It’s obvious to outsiders that this was a cult, but not so to those caught up in it. It took years and repeated allegations for people to wake up to faked healings, sexual abuse, and the ceding of control to a megalomaniac who got rich off of duping and exploiting followers. This book won the inaugural Fitzcarraldo Editions Essay Prize. I admired its blend of journalistic and confessional styles: research, interviews with friends and strangers alike, and reflection on the author’s own loss of faith. He gets to the heart of why people stayed: “A feeling of holding and of being held. A sense of fellowship and interdependence … the rare moments of transcendence … It was nice to be a superorganism.” This gripped me from page one, but its wider appeal strikes me as limited. For me, it was the perfect chance to think about how I might write about traditions I grew up in and spurned.

“Immanuel was the centre of the world once. Long after it imploded, its gravitational pull remains.” McNaught grew up in an evangelical church in Winchester, England, but by the time he left for university he’d fallen away. Meanwhile, some peers left for Nigeria to become disciples at charismatic preacher TB Joshua’s Synagogue Church of All Nations in Lagos. It’s obvious to outsiders that this was a cult, but not so to those caught up in it. It took years and repeated allegations for people to wake up to faked healings, sexual abuse, and the ceding of control to a megalomaniac who got rich off of duping and exploiting followers. This book won the inaugural Fitzcarraldo Editions Essay Prize. I admired its blend of journalistic and confessional styles: research, interviews with friends and strangers alike, and reflection on the author’s own loss of faith. He gets to the heart of why people stayed: “A feeling of holding and of being held. A sense of fellowship and interdependence … the rare moments of transcendence … It was nice to be a superorganism.” This gripped me from page one, but its wider appeal strikes me as limited. For me, it was the perfect chance to think about how I might write about traditions I grew up in and spurned. Like other short works I’ve read by Hispanic women authors (

Like other short works I’ve read by Hispanic women authors ( I knew from

I knew from  The epigraph is from the two pages of laughter (“Ha!”) in “Real Estate,” one of the stories of

The epigraph is from the two pages of laughter (“Ha!”) in “Real Estate,” one of the stories of