Book Serendipity, January to February

I call it “Book Serendipity” when two or more books that I read at the same time or in quick succession have something in common – the more bizarre, the better. This is a regular feature of mine every couple of months. Because I usually have 20–30 books on the go at once, I suppose I’m more prone to such incidents. People frequently ask how I remember all of these coincidences. The answer is: I jot them down on scraps of paper or input them immediately into a file on my PC desktop; otherwise, they would flit away! Feel free to join in with your own.

The following are in roughly chronological order.

- An old woman with purple feet (due to illness or injury) in one story of Brawler by Lauren Groff and John of John by Douglas Stuart.

- Someone is pushed backward and dies of the head injury in Zofia Nowak’s Book of Superior Detecting by Piotr Cieplak and one story of Brawler by Lauren Groff.

- The Hindenburg disaster is mentioned in A Long Game by Elizabeth McCracken and Evensong by Stewart O’Nan.

- Reluctance to cut into a corpse during medical school and the dictum ‘see one, do one, teach one’ in the graphic novel See One, Do One, Teach One: The Art of Becoming a Doctor by Grace Farris and Separate by C. Boyhan Irvine.

A remote Scottish island setting and a harsh father in Muckle Flugga by Michael Pedersen [Shetland] and John of John by Douglas Stuart [Harris]. (And another Scottish island setting in A Calendar of Love by George Mackay Brown [Orkney].)

A remote Scottish island setting and a harsh father in Muckle Flugga by Michael Pedersen [Shetland] and John of John by Douglas Stuart [Harris]. (And another Scottish island setting in A Calendar of Love by George Mackay Brown [Orkney].)

- A mention of genuine Harris tweed in Alone in the Classroom by Elizabeth Hay and John of John by Douglas Stuart.

- The Katharine Hepburn film The Philadelphia Story is mentioned in The Girls’ Guide to Hunting and Fishing by Melissa Bank and Woman House by Lauren W. Westerfield.

- A mention of Icelandic poppies in Nighthawks by Lisa Martin and Boundless by Kathleen Winter.

- Vita Sackville-West is mentioned in the Orlando graphic novel adaptation by Susanne Kuhlendahl and Boundless by Kathleen Winter.

- Fear of bear attacks in Black Bear by Trina Moyles and Boundless by Kathleen Winter. Bears also feature in A Rough Guide to the Heart by Pam Houston and No Paradise with Wolves by Katie Stacey. [Looking through children’s picture books at the library the other week, I was struck by how many have bears in the title. Dozens!]

- I was reading books called Memory House (by Elaine Kraf) and Woman House (by Lauren W. Westerfield) at the same time, both of them pre-release books for Shelf Awareness reviews.

- An adolescent girl is completely ignorant of the facts of menstruation in I Who Have Never Known Men by Jacqueline Harpman and Carrie by Stephen King.

- Camembert is eaten in The Honesty Box by Lucy Brazier and Ordinary Saints by Niamh Ni Mhaoileoin.

- A herbal tonic is sought to induce a miscarriage in The Girls Who Grew Big by Leila Mottley and Bog Queen by Anna North.

- Vicks VapoRub is mentioned in Love Invents Us by Amy Bloom, Kin by Tayari Jones, and Dirt Rich by Graeme Richardson.

- An adolescent girl only admits to her distant mother that she’s gotten her first period because she needs help dealing with a stain (on her bedding / school uniform) in Love Invents Us by Amy Bloom, An Experiment in Love by Hilary Mantel, and Ordinary Saints by Niamh Ni Mhaoileoin. (I had to laugh at the mother asking the narrator of the Mantel: “Have you got jam on your underskirt?”) Basically, first periods occurred a lot in this set! They are also mentioned in A Little Feral by Maria Giesbrecht and one story of The Blood Year Daughter by G.G. Silverman. [I also had three abortion scenes in this cycle, but I think it would constitute spoilers to say which novels they appeared in.)

- A casual job cleaning pub/bar toilets in Kin by Tayari Jones and John of John by Douglas Stuart.

- Kansas City is a location mentioned in Strangers by Belle Burden, Mrs. Bridge by Evan S. Connell, and Dreams in Which I’m Almost Human by Hannah Soyer. (Not actually sure if that refers to Kansas or Missouri in two of them.)

- The notion of “flirting with God” is mentioned in Love Invents Us by Amy Bloom and A Little Feral by Maria Giesbrecht.

- A signature New Orleans cocktail, the Sazerac (a variation on the whisky old-fashioned containing absinthe), appears in Kin by Tayari Jones and Let the Bad Times Roll by Alice Slater.

- An older person’s smell brings back childhood memories in Love Invents Us by Amy Bloom and Whistler by Ann Patchett.

- The fact that complaining of chest pain will get you seen right away in an emergency room is mentioned in Love Invents Us by Amy Bloom and The Girls Who Grew Big by Leila Mottley.

- Thickly buttered toast is a favoured snack in The Honesty Box by Lucy Brazier and An Experiment in Love by Hilary Mantel.

A scene of trying on fur coats in Love Invents Us by Amy Bloom and An Experiment in Love by Hilary Mantel.

A scene of trying on fur coats in Love Invents Us by Amy Bloom and An Experiment in Love by Hilary Mantel.

- Lime and soda is drunk in Our Numbered Bones by Katya Balen, Kin by Tayari Jones, and Whistler by Ann Patchett.

- A husband 17 years older than his wife in Kin by Tayari Jones and Whistler by Ann Patchett.

- The protagonist seems to hold a special attraction for old men in Love Invents Us by Amy Bloom and Whistler by Ann Patchett.

- A tattoo of a pottery shard (her ex-husband’s) in Strangers by Belle Burden and one of an arrowhead (her own) in Dreams in Which I’m Almost Human by Hannah Soyer.

- A relationship with an older editor at a publishing house: The Girls’ Guide to Hunting and Fishing by Melissa Bank (romantic) and Whistler by Ann Patchett (stepfather–stepdaughter).

- Repeated vomiting and a fever of 103–104°F leads to a diagnosis of appendicitis in My Grandmothers and I by Diana Holman-Hunt and Whistler by Ann Patchett.

Multiple pet pugs in Strangers by Belle Burden and My Grandmothers and I by Diana Holman-Hunt.

Multiple pet pugs in Strangers by Belle Burden and My Grandmothers and I by Diana Holman-Hunt.

- Palm crosses are mentioned in My Grandmothers and I by Diana Holman-Hunt and Kin by Tayari Jones.

- A Miss Jemison in Kin by Tayari Jones and a Miss Jamieson in Elizabeth and Ruth by Livi Michael.

- Pasley as a surname in Elizabeth and Ruth by Livi Michael and a place name (Pasley Bay) in Boundless by Kathleen Winter.

- A remark on a character’s unwashed hair in My Grandmothers and I by Diana Holman-Hunt and Let the Bad Times Roll by Alice Slater.

- A mention of a monkey’s paw in Museum Visits by Éric Chevillard and Let the Bad Times Roll by Alice Slater.

- A character gets 26 (22) stitches in her face (head) after a car accident, a young person who’s vehemently anti-smoking, and a mention of being dusted orange from eating Cheetos, in Whistler by Ann Patchett and Let the Bad Times Roll by Alice Slater.

- Pre-eclampsia occurs in Strangers by Belle Burden and The Girls Who Grew Big by Leila Mottley.

- There’s a chapter on searching for corncrakes on the Isle of Coll (the Inner Hebrides of Scotland) in The Edge of Silence by Neil Ansell, which I read last year; this year I reread the essay on the same topic in Findings by Kathleen Jamie.

- Worry over women with long hair being accidentally scalped – if a horse steps on her ponytail in Mare by Emily Haworth-Booth; if trapped in a London Underground escalator in Leaving Home by Mark Haddon.

A pet ferret in My Grandmothers and I by Diana Holman-Hunt and Shooting Up by Jonathan Tepper.

A pet ferret in My Grandmothers and I by Diana Holman-Hunt and Shooting Up by Jonathan Tepper.

- A dodgy doctor who molests a young female patient in Leaving Home by Mark Haddon and Elizabeth and Ruth by Livi Michael.

- A high school girl’s inappropriate relationship with her English teacher is the basis for Love Invents Us by Amy Bloom, and then Half His Age by Jennette McCurdy, which I started soon after.

- College roommates who become same-sex lovers, one of whom goes on to have a heterosexual marriage, in Kin by Tayari Jones and Whistler by Ann Patchett.

- A mention of Sephora (the cosmetics shop) in Half His Age by Jennette McCurdy and Whistler by Ann Patchett.

- A discussion of the Greek mythology character Leda in Mrs. Bridge by Evan S. Connell and Whistler by Ann Patchett (where it’s also a character name).

- A workaholic husband who rarely sees his children and leaves their care to his wife in Strangers by Belle Burden and Mrs. Bridge by Evan S. Connell.

- An apparently wealthy man who yet steals food in Strangers by Belle Burden and Let the Bad Times Roll by Alice Slater.

- Characters named Lulubelle in Mrs. Bridge by Evan S. Connell and Lulabelle in Kin by Tayari Jones.

- Characters named Ruth in Mrs. Bridge by Evan S. Connell, Kin by Tayari Jones, and Elizabeth and Ruth by Livi Michael.

A mention of Mary McLeod Bethune in Negroland by Margo Jefferson and Kin by Tayari Jones.

A mention of Mary McLeod Bethune in Negroland by Margo Jefferson and Kin by Tayari Jones.

- Doing laundry at a whorehouse in Kin by Tayari Jones and Elizabeth and Ruth by Livi Michael.

- A male character nicknamed Doll in John of John by Douglas Stuart and then Elizabeth and Ruth by Livi Michael.

- A mention of tuberculosis of the stomach in Findings by Kathleen Jamie and Shooting Up by Jonathan Tepper. I was also reading a whole book on tuberculosis, Everything Is Tuberculosis by John Green, at the same time.

- Mention of Doberman dogs in Mrs. Bridge by Evan S. Connell and one story of The Blood Year Daughter by G.G. Silverman.

- Extreme fear of flying in Leaving Home by Mark Haddon and Whistler by Ann Patchett.

What’s the weirdest reading coincidence you’ve had lately?

Three on a Theme: Armchair Travels at the Italian Coast (Rachel Joyce, Sarah Moss and Jess Walter – #18 of 20 Books)

I’ve done a lot of journeying through Italy’s lakes and islands this summer. Not in real life, thank goodness – it would be far too hot! – but via books. I started with the Moss, then read the Joyce, and rounded off with the Walter, a book that had been on my TBR for 12 years and that many had heartily recommended, so I was delighted to finally experience it for myself.

The Homemade God by Rachel Joyce (2025)

Joyce has really upped her game. I’ve somehow read all of her books though I often found them, from Harold Fry onward, disappointingly sentimental and twee. But with this she’s entering the big leagues, moving into the more expansive, elegant and empathetic territory of novels by Anne Enright (The Green Road), Patrick Gale (Notes from an Exhibition), Maggie O’Farrell (Instructions for a Heatwave) and Tom Rachman (The Italian Teacher). It’s the story of four siblings, initially drawn together and then dramatically blown apart by their father’s death. Despite weighty themes of alcoholism, depression and marital struggles, there is an overall lightness of tone and style that made this a pleasure to read.

Vic Kemp, the title figure, was a larger-than-life, womanizing painter whose work divided critics. After his first wife’s early death from cancer, he raised three daughters and a son with the help of a rotating cast of nannies (whom he inevitably slept with). At 76 he delivered the shocking news that he was marrying again: Bella-Mae, an artist in her twenties – much younger than any of his children. They moved from London to his second home in Italy just weeks before he drowned in Lake Orta. Netta, the eldest daughter, is sure there’s something fishy; he knew the lake so well and would never have gone out for a swim with a mist rolling in. Did Bella-Mae kill him for his money? And where is his last painting? Funny how waiting for an autopsy report and searching for a new will and carping with siblings over the division of belongings can ruin what should be paradise.

The interactions between Netta, Susan, Goose (Gustav) and Iris, plus Bella-Mae and her cousin Laszlo, are all flawlessly done, and through flashbacks and surges forward we learn so much about these flawed and flailing characters. The derelict villa and surrounding small town are appealing settings, and there are a lot of intriguing references to food, fashion and modern art.

My only small points of criticism are that Iris is less fleshed out than the others (and her bombshell secret felt distasteful), and that Joyce occasionally resorts to delivering some of her old obvious (though true) messages through an omniscient narrator, whereas they could be more palatable if they came out organically in dialogue or indirectly through a character’s thought process. Here’s an example: “When someone dies or disappears, we can only tell stories about what might have been the case or what might have happened next.” (One I liked better: “There were some things you never got over. No amount of thinking or talking would make them right: the best you could do was find a way to live alongside them.”) I also don’t think Goose would have been able to view his father’s body more than two months after his death; even with embalming, it would have started to decay within weeks.

You can tell that Joyce got her start in theatre because she’s so good at scenes and dialogue, and at moving people into different groups to see what they’ll do. She’s taken the best of her work in other media and brought it to bear here. It’s fascinating how Goose starts off seeming minor and eventually becomes the main POV character. And ending with a wedding (good enough for a Shakespearean comedy) offers a lovely occasion for a potential reconciliation after a (tragi)comic plot. More of this calibre, please! (Public library) ![]()

Ripeness by Sarah Moss (2025)

One sneaky little line, “Ripeness, not readiness, is all,” a Shakespeare mash-up (“Ripeness is all” is from King Lear vs. “the readiness is all” is from Hamlet), gives a clue to how to understand this novel: As a work of maturity from Sarah Moss, presenting life with all its contradictions and disappointments, not attempting to counterbalance that realism with any false optimism. What do we do, who will we be, when faced with situations for which we aren’t prepared?

Now that she’s based in Ireland, Moss seems almost to be channelling Irish authors such as Claire Keegan and Maggie O’Farrell. The line-up of themes – ballet + sisters + ambivalent motherhood + the question of immigration and belonging – should have added up to something incredible and right up my street. While Ripeness is good, even very good, it feels slightly forced. As has been true with some of Moss’s recent fiction (especially Summerwater), there is the air of a creative writing experiment. Here the trial is to determine which feels closer, a first-person rendering of a time nearly 60 years ago, or a present-tense, close-third-person account of the now. [I had in mind advice from one of Emma Darwin’s Substack posts: “What you’ll see is that ‘deep third’ is really much the same as first, in the logic of it, just with different pronouns: you are locking the narrative into a certain character’s point-of-view, but you don’t have a sense of that character as the narrator, the way you do in first person.” Except, increasingly as the novel goes on, we are compelled to think about Edith as a narrator, of her own life and others’.

In the current story line, everyone in rural West Ireland seems to have come from somewhere else (e.g. Edith’s lover Gunter is German). “She’s going to have to find a way to rise above it, this tribalism,” Edith thinks. She’s aghast at her town playing host to a small protest against immigration. Fair enough, but including this incident just seems like an excuse for some liberal handwringing (“since it’s obvious that there is enough for all, that the problem is distribution not supply, why cannot all have enough? Partly because people like Edith have too much.”). The facts of Maman being French-Israeli and having lost family in the Holocaust felt particularly shoehorned in; referencing Jewishness adds nothing. I also wondered why she set the 1960s narrative in Italy, apart from novelty and personal familiarity. (Teenage Edith’s high school Italian is improbably advanced, allowing her to translate throughout her sister’s childbirth.)

Though much of what I’ve written seems negative, I was left with an overall favourable impression. Mostly it’s that the delivery scene and the chapters that follow it are so very moving. Plus there are astute lines everywhere you look, whether on dance, motherhood, or migration. It may simply be that Moss was taking on too much at once, such that this lacks the focus of her novellas. Ultimately, I would have been happy to have just the historical story line; the repeat of the surrendering for adoption element isn’t necessary to make any point. (I was relieved, anyway, that Moss didn’t resort to the cheap trick of having the baby turn out to be a character we’ve already been introduced to.) I admire the ambition but feel Moss has yet to return to the sweet spot of her first five novels. Still, I’m a fan for life. (Public library) ![]()

#18 of my 20 Books of Summer

(Completing the second row on the Bingo card: Book set in a vacation destination)

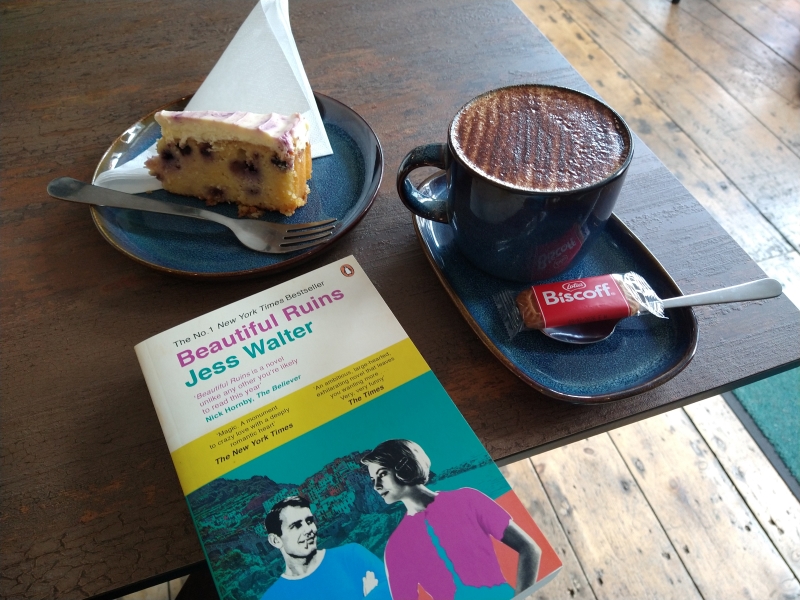

Beautiful Ruins by Jess Walter (2012)

I loved how Emma Straub described the ideal summer read in one of her Substack posts: “My plan for the summer is to read as many books as possible that make me feel that drugged-up feeling, where you just want to get back to the page.” I wish I’d been able to read this faster – that I hadn’t had so much on my plate all summer so I could have been fully immersed. Nonetheless, every time I returned to it I felt welcomed in. So many trusted bibliophiles love this book – blogger friends Laila and Laura T.; Emma Milne-White, owner of Hungerford Bookshop, who plugged it at their 2023 summer reading celebration; and Maris Kreizman, who in a recent newsletter described this as “One of my favorite summer reading novels ever … escapist magic, a lush historical novel.”

I loved how Emma Straub described the ideal summer read in one of her Substack posts: “My plan for the summer is to read as many books as possible that make me feel that drugged-up feeling, where you just want to get back to the page.” I wish I’d been able to read this faster – that I hadn’t had so much on my plate all summer so I could have been fully immersed. Nonetheless, every time I returned to it I felt welcomed in. So many trusted bibliophiles love this book – blogger friends Laila and Laura T.; Emma Milne-White, owner of Hungerford Bookshop, who plugged it at their 2023 summer reading celebration; and Maris Kreizman, who in a recent newsletter described this as “One of my favorite summer reading novels ever … escapist magic, a lush historical novel.”

I’m relieved to report that Beautiful Ruins lived up to everyone’s acclaim – and my own high expectations after enjoying Walter’s So Far Gone, which I reviewed for BookBrowse earlier in the summer. I was immediately captivated by the shabby glamour of Pasquale’s hotel in Porto Vergogna on the coast of northern Italy. With refreshing honesty, he’s dubbed the place “Hotel Adequate View.” In April 1962, he’s attempting to build a cliff-edge tennis court when a boat delivers beautiful, dying American actress Dee Moray. It soon becomes clear that her condition is nothing nine months won’t fix and she’s been dumped here to keep her from meddling in the romance between the leads in Cleopatra, filming in Rome. In the present day, an elderly Pasquale goes to Hollywood to find out whatever happened to Dee.

A myriad of threads and formats – a movie pitch, a would-be Hemingway’s first chapter of a never-finished wartime masterpiece, an excerpt from a producer’s autobiography and a play transcript – coalesce to flesh out what happened in that summer of 1962 and how the last half-century has treated all the supporting players. True to the tone of a novel about regret, failure and shattered illusions, Walter doesn’t tie everything up neatly, but he does offer a number of the characters a chance at redemption. This felt to me like a warmer and more timeless version of A Visit from the Goon Squad. There are so many great scenes, none better than Richard Burton’s drunken visit to Porto Vergogna, which had me in stitches. Fantastic. (Hungerford Bookshop – 40th birthday gift from my husband from my wish list) ![]()

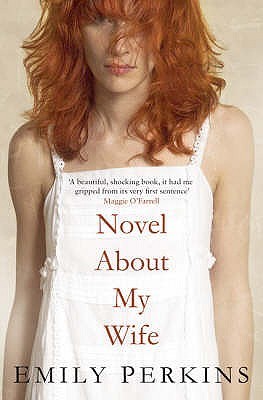

Literary Wives Club: Novel About My Wife by Emily Perkins (2008)

Although Emily Perkins was a new name to me, the New Zealand author has published five novels and a short story collection. Unfortunately, I never engaged with her London-set Novel About My Wife. On the one hand, it must have been an intriguing challenge for Perkins to inhabit a man’s perspective and examine how a widower might recreate his marriage and his late wife’s mental state. “I can’t speak for Ann[,] obviously, only about her,” screenwriter Tom Stone admits. On the other hand, Tom is so egotistical and self-absorbed that his portrait of Ann is more obfuscating than illuminating.

Although Emily Perkins was a new name to me, the New Zealand author has published five novels and a short story collection. Unfortunately, I never engaged with her London-set Novel About My Wife. On the one hand, it must have been an intriguing challenge for Perkins to inhabit a man’s perspective and examine how a widower might recreate his marriage and his late wife’s mental state. “I can’t speak for Ann[,] obviously, only about her,” screenwriter Tom Stone admits. On the other hand, Tom is so egotistical and self-absorbed that his portrait of Ann is more obfuscating than illuminating.

“If I could build her again using words, I would,” he opens, but that promising start just leads into paragraphs of physical description. Bare facts, such as that Ann was from Sydney and created radiation masks for cancer patients in a hospital, are hardly revealing. We mostly know Ann through her delusions. In her late thirties, when she was three months pregnant with their son Arlo, she was caught in an underground train derailment. Thereafter, she increasingly fell victim to paranoia, believing that she was being stalked and that their house was infested. We’re invited to speculate that pregnancy exacerbated her mental health issues and that postpartum psychosis may have had something to do with her death.

I mostly skimmed the novel, so I may have missed some plot points, but what stood out to me were Tom’s unpleasant depictions of women and complaints about his faltering career. (He’s envious of a new acquaintance, Simon, who’s back and forth to Hollywood all the time for successful screenwriting projects.) Interspersed are seemingly pointless excerpts from Tom’s screenplay about a trip he and Ann took to Fiji. I longed for the balance of another perspective. This had a bit of the flavour of early Maggie O’Farrell, but none of the warmth. (Secondhand – Awesomebooks.com) ![]()

The main question we ask about the books we read for Literary Wives is:

What does this book say about wives or about the experience of being a wife?

Being generous to Perkins, perhaps the very point she was trying to make is that it’s impossible to get outside of one’s own perspective and understand what’s going on with a spouse, especially one who has mental health struggles. Had Tom been more attentive and supportive, might things have ended differently?

See Becky’s, Kate’s and Kay’s reviews, too! (Naomi is on a break this month.)

Coming up next, in December: The Soul of Kindness by Elizabeth Taylor.

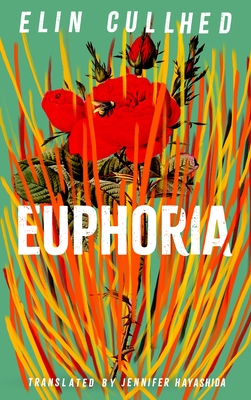

Literary Wives Club: Euphoria by Elin Cullhed (2021)

Swedish author Elin Cullhed won the August Prize and was a finalist for the Strega European Prize with this first novel for adults. Euphoria is a recreation of Sylvia Plath’s state of mind in the last year of her life. It opens on 7 December 1962 in Devon with a list headed “7 REASONS NOT TO DIE,” most of which centre on her children, Frieda and Nick. She enumerates the pleasures of being in a physical body and enjoying coastal scenery. But she also doesn’t want to give her husband, poet Ted Hughes, the satisfaction of having his prophecies about her mental illness come true.

Flash back to the year before, when Plath is heavily pregnant with Nick during a cold winter and trying to steal moments to devote to writing. She feels gawky and out of place in encounters with the vicar and shopkeeper of their English village. “Who was I, who had let everything become a compromise between Ted’s Celtic chill and my grandiose American bluster?” She and Hughes have an intensely physical bond, but jealousy of each other’s talents and opportunities – as well as his serial adultery and mean and controlling nature – erodes their relationship. The book ends in possibility, with Plath just starting to glimpse success as The Bell Jar readies for publication and a collection of poems advances. Readers are left with that dramatic irony.

Flash back to the year before, when Plath is heavily pregnant with Nick during a cold winter and trying to steal moments to devote to writing. She feels gawky and out of place in encounters with the vicar and shopkeeper of their English village. “Who was I, who had let everything become a compromise between Ted’s Celtic chill and my grandiose American bluster?” She and Hughes have an intensely physical bond, but jealousy of each other’s talents and opportunities – as well as his serial adultery and mean and controlling nature – erodes their relationship. The book ends in possibility, with Plath just starting to glimpse success as The Bell Jar readies for publication and a collection of poems advances. Readers are left with that dramatic irony.

Cullhed seems to hew to biographical detail, though I’m not particularly familiar with the Hughes–Plath marriage. Scenes of their interactions with neighbours, Plath’s mother, and Ted’s lover Assia Wevill make their dynamic clear. The prose grows more nonstandard; run-on sentences and all-caps phrases indicate increasing mania. There are also lovely passages that seem apt for a poet: “Ted’s crystalline sly little mint lozenge eyes. Narrow foxish. Thin hard. His eyes, so embittered.” The use of language is effective at revealing Plath’s maternal ambivalence and shaky mental health. Somehow, though, I found this quite tedious by the end. Not among my favourite biographical novels, but surely a must-read for Plath fans. ![]()

Translated from the Swedish by Jennifer Hayashida in 2022 – our first read in translation, I think? And what a brilliant cover.

With thanks to Canongate for the free copy for review.

The main question we ask about the books we read for Literary Wives is:

What does this book say about wives or about the experience of being a wife?

Marriage is claustrophobic here, as in so many of the books we read. Much as she loves her children, Plath finds the whole wifehood–motherhood complex to be oppressive and in direct conflict with her ambitions as an author. Sharing a vocation with her husband, far from helping him understand her, only makes her more bitter that he gets the time and exposure she so longs for. More than 60 years later, Plath’s death still echoes, a tragic loss to literature.

See Kate’s, Kay’s and Naomi’s reviews, too!

Coming up next, in March: Lessons in Chemistry by Bonnie Garmus – I’ve read this before but will plan to skim back through a copy from the library.

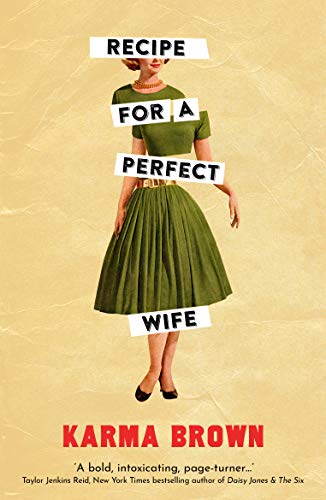

Literary Wives Club: Recipe for a Perfect Wife by Karma Brown (2019)

{SPOILERS IN THIS REVIEW!}

Canadian author Karma Brown’s fifth novel features two female protagonists who lived in the same house in different decades. The dual timeline, which plays out in alternating chapters, contrasts the mid-1950s and late 2010s to ask 1) whether the situation of women has really improved and 2) if marriage is always and inevitably an oppressive force.

Nellie Murdoch loves cooking and gardening – great skills for a mid-twentieth-century housewife – but can’t stay pregnant, which provokes the anger of her abusive husband, Richard. To start with, Alice Hale can’t cook or garden for toffee and isn’t sure she wants a baby at all, but as she reads through Nellie’s unsent letters and recipes, interspersed with Ladies’ Home Journal issues in the boxes in the basement, she starts to not just admire Nellie but emulate her. She’s keeping several things from her husband Nate: she was fired from her publicist job after a pre-#MeToo scandal involving a handsy male author, she’s had an IUD fitted, and she’s made zero progress on the novel she’s supposed to be writing. But Nellie’s correspondence reveals secrets that inspire Alice to compose Recipe for a Perfect Wife.

The chapter epigraphs, mostly from period etiquette and relationship guides for young wives, provide ironic commentary on this pair of not-so-perfect marriages. Brown has us wondering how closely Alice will mirror Nellie’s trajectory (aborting her pregnancy? poisoning her husband?). There were clichéd elements, such as Richard’s adultery, glitzy New York City publishing events, Alice’s quirky-funny friend, and each woman having a kindly elderly (maternal) neighbour who looks out for her and gives her valuable advice. I felt uncomfortable with how Nellie’s mother’s suicide makes it seem like Nellie’s radical acts are borne out of inherited mental illness rather than a determination to make her own path.

Often, I felt Brown was “phoning it in,” if that phrase means anything to you. In other words, playing it safe and taking an easy and previously well-trodden path. Parallel stories like this can be clever, or can seem too simple and coincidental. However, I can affirm that the novel is highly readable and has vintage charm. I always enjoy epistolary inclusions like letters and recipes, and it was intriguing to see how Nellie uses her garden herbs and flowers for pharmaceutical uses. Our first foxglove just came into flower – eek! (Kindle purchase) ![]()

The main question we ask about the books we read for Literary Wives is:

What does this book say about wives or about the experience of being a wife?

- Being a wife does not have to mean being a housewife. (It also doesn’t have to mean being a mother, if you don’t want to be one.)

- Secrets can be lethal to a marriage. Even if they aren’t literally so, they’re a really bad idea.

This was, overall, a very bleak picture of marriage. In the 1950s strand there is a scene of marital rape – one of two I’ve read recently, and I find these particularly difficult to take. Alice’s marriage might not have blown up as dramatically, but still doesn’t appear healthy. She forced Nate to choose between her and the baby, and his job promotion in California. The fallout from that ultimatum is not going to make for a happy relationship. I almost thought that Nellie wields more power. However, both women get ahead through deception and manipulation. I think we are meant to cheer for what they achieve, and I did for Nellie’s revenge at Richard’s vileness, but Alice I found brattish and calculating.

See Kate’s, Kay’s and Naomi’s reviews, too!

Coming up next, in September: Their Eyes Were Watching God by Zora Neale Hurston.

Reading about Mothers and Motherhood: Cosslett, Cusk, Emma Press Poetry, Heti, and Pachico

It was (North American) Mother’s Day at the weekend, an occasion I have complicated feelings about now that my mother is gone. But I don’t think I’ll ever stop reading and writing about mothering. At first I planned to divide my recent topical reads (one a reread) into two sets, one for ambivalence about becoming a mother and the other for mixed feelings about one’s mother. But the two are intertwined – especially in the poetry anthology I consider below – such that they feel more like facets of the same experience. I also review two memoirs (one classic; one not so much) and two novels (autofiction vs. science fiction).

The Year of the Cat: A Love Story by Rhiannon Lucy Cosslett (2023)

This was on my Most Anticipated list last year. A Covid memoir that features adopting a cat and agonizing over the question of whether to have a baby sounded right up my street. And in the earlier pages, in which Cosslett brings Mackerel the kitten home during the first lockdown and interrogates the stereotype of the crazy cat lady from the days of witches’ familiars onwards, it indeed seemed to be so. But the further I got, the more my pace through the book slowed to a limp; it took me 10 months to read, in fits and starts.

I’ve struggled to pinpoint what I found so off-putting, but I have a few hypotheses: 1) By the time I got hold of this, I’d tired of Covid narratives. 2) Fragmentary narratives can seem like profound reflections on subjectivity and silences. But Cosslett’s strategy of bouncing between different topics – worry over her developmentally disabled brother, time working as an au pair in France, PTSD from an attempted strangling by a stranger in London and being in Paris on the day of the Charlie Hebdo terrorist attack – with every page or even every paragraph, feels more like laziness or arrogance. Of course the links are there; can’t you see them?

I’ve struggled to pinpoint what I found so off-putting, but I have a few hypotheses: 1) By the time I got hold of this, I’d tired of Covid narratives. 2) Fragmentary narratives can seem like profound reflections on subjectivity and silences. But Cosslett’s strategy of bouncing between different topics – worry over her developmentally disabled brother, time working as an au pair in France, PTSD from an attempted strangling by a stranger in London and being in Paris on the day of the Charlie Hebdo terrorist attack – with every page or even every paragraph, feels more like laziness or arrogance. Of course the links are there; can’t you see them?

3) Cosslett claims to reject clichéd notions about pets being substitutes for children, then goes right along with them by presenting Mackerel as an object of mothering (“there is something about looking after her that has prodded the carer in me awake”) and setting up a parallel between her decision to adopt the kitten and her decision to have a child. “Though I had all these very valid reasons not to get a cat, I still wanted one,” she writes early on. And towards the end, even after she’s considered all the ‘very valid reasons’ not to have a baby, she does anyway. “I need to find another way of framing it, if I am to do it,” she says. So she decides that it’s an expression of bravery, proof of overcoming trauma. I was unconvinced. When people accuse memoirists of being navel-gazing, this is just the sort of book they have in mind. I wonder if those familiar with her Guardian journalism would agree. (Public library)

A Life’s Work: On Becoming a Mother by Rachel Cusk (2001)

When this was first published, Cusk was vilified for “hating” her child – that is, for writing honestly about the bewilderment and misery of early motherhood. We’ve moved on since then. Now women are allowed to admit that it’s not all cherubs and lullabies. I suspect what people objected to was the unemotional tone: Cusk writes like an anthropologist arriving in a new land. The style is similar to her novels’ in that she can seem detached because of her dry wit, elevated diction and frequent literary allusions.

When this was first published, Cusk was vilified for “hating” her child – that is, for writing honestly about the bewilderment and misery of early motherhood. We’ve moved on since then. Now women are allowed to admit that it’s not all cherubs and lullabies. I suspect what people objected to was the unemotional tone: Cusk writes like an anthropologist arriving in a new land. The style is similar to her novels’ in that she can seem detached because of her dry wit, elevated diction and frequent literary allusions.

I understand that crying, being the baby’s only means of communication, has any number of causes, which it falls to me, as her chief companion and link to the world, to interpret.

Have you taken her to toddler group, the health visitor enquired. I had not. Like vaccinations and mother and baby clinics, the notion instilled in me a deep administrative terror.

We [new parents] are heroic and cruel, authoritative and then servile, cleaving to our guesses and inspirations and bizarre rituals in the absence of any real understanding of what we are doing or how it should properly be done.

She approaches mumsy things as an outsider, clinging to intellectualism even though it doesn’t seem to apply to this new world of bodily obligation, “the rambling dream of feeding and crying that my life has become.” By the end of the book, she does express love for and attachment to her daughter, built up over time and through constant presence. But she doesn’t downplay how difficult it was. “For the first year of her life work and love were bound together, fiercely, painfully.” This is a classic of motherhood literature, and more engaging than anything else I’ve read by Cusk. (Secondhand purchase – Awesomebooks.com)

The Emma Press Anthology of Motherhood, ed. by Rachel Piercey and Emma Wright (2014)

There’s a great variety of subject matter and tone here, despite the apparently narrow theme. There are poems about pregnancy (“I have a comfort house inside my body” by Ikhda Ayuning Maharsi), childbirth (“The Tempest” by Melinda Kallismae) and new motherhood, but also pieces imagining the babies that never were (“Daughters” by Catherine Smith) or revealing the complicated feelings adults have towards their mothers.

“All My Mad Mothers” by Jacqueline Saphra depicts a difficult bond through absurdist metaphors: “My mother was so hard to grasp: once we found her in a bath / of olive oil, or was it sesame, her skin well-slicked / … / to ease her way into this world. Or out of it.” I also loved her evocation of a mother–daughter relationship through a rundown of a cabinet’s contents in “My Mother’s Bathroom Armoury.”

In “My Mother Moves into Adolescence,” Deborah Alma expresses exasperation at the constant queries and calls for help from someone unconfident in English. “This, then, is how you should pray” by Flora de Falbe cleverly reuses the structure of the Lord’s Prayer as she sees her mother returning to independent life and a career as her daughter prepares to leave home. “I will hold you / as you held me / my mother – / yours are the bathroom catalogues / and the whole of a glorious future.”

In “My Mother Moves into Adolescence,” Deborah Alma expresses exasperation at the constant queries and calls for help from someone unconfident in English. “This, then, is how you should pray” by Flora de Falbe cleverly reuses the structure of the Lord’s Prayer as she sees her mother returning to independent life and a career as her daughter prepares to leave home. “I will hold you / as you held me / my mother – / yours are the bathroom catalogues / and the whole of a glorious future.”

I connected with these perhaps more so than the poems about becoming a mother, but there are lots of strong entries and very few unmemorable ones. Even within the mothers’ testimonials, there is ambivalence: the visceral vocabulary in “Collage” by Anna Kisby is rather morbid, partway to gruesome: “You look at me // like liver looks at me, like heart. You are familiar as innards. / In strip-light I clean your first shit. I’m not sure I do it right. / It sticks to me like funeral silk. … There is a window // guillotined into the wall. I scoop you up like a clod.”

A favourite pair: “Talisman” by Anna Kirk and “Grasshopper Warbler” by Liz Berry, on facing pages, for their nature imagery. “Child, you are grape / skins stretched over fishbones. … You are crab claws unfurling into cabbage leaves,” Kirk writes. Berry likens pregnancy to patient waiting for an elusive bird by a reedbed. (Free copy – newsletter giveaway)

Motherhood by Sheila Heti (2018)

I first read this nearly six years ago (see my original review), when I was 34; I’m now 40 and pretty much decided against having children, but FOMO is a lingering niggle. Even though I already owned it in hardback, I couldn’t resist picking up a nearly new paperback I saw going for 50 pence in a charity shop, if only for the Leanne Shapton cover – her simple, elegant watercolour style is instantly recognizable. Having a different copy also provided some novelty for my reread, which is ongoing; I’m about 80 pages from the end.

I’m not finding Heti’s autofiction musings quite as profound this time around, and I can’t deny that the book is starting to feel repetitive, but I’ve still marked more than a dozen passages. Pondering whether to have children is only part of the enquiry into what a woman artist’s life should be. The intergenerational setup stands out to me again as Heti compares her Holocaust survivor grandmother’s short life with her mother’s practical career and her own creative one.

I’m not finding Heti’s autofiction musings quite as profound this time around, and I can’t deny that the book is starting to feel repetitive, but I’ve still marked more than a dozen passages. Pondering whether to have children is only part of the enquiry into what a woman artist’s life should be. The intergenerational setup stands out to me again as Heti compares her Holocaust survivor grandmother’s short life with her mother’s practical career and her own creative one.

For the past month or so, I’ve also been reading Alphabetical Diaries, so you could say that I’m pretty Heti-ed out right now, but I do so admire her for writing exactly what she wants to and sticking to no one else’s template. People probably react against Heti’s work as self-indulgent in the same way I did with Cosslett’s, but the former’s shtick works for me. (Secondhand purchase – Bas Books & Home, Newbury)

A few of the passages that have most struck me on this second reading:

I think that is how childbearing feels to me: a once-necessary, now sentimental gesture.

I don’t want ‘not a mother’ to be part of who I am—for my identity to be the negative of someone else’s positive identity.

The whole world needs to be mothered. I don’t need to invent a brand new life to give the warming effect to my life I imagine mothering will bring.

I have to think, If I wanted a kid, I already would have had one by now—or at least I would have tried.

Jungle House by Julianne Pachico (2023)

{BEWARE SPOILERS}

Pachico’s third novel is closer to sci-fi than I might have expected. Apart from Lena, the protagonist, all the major characters are machines or digital recreations: AI, droids, a drone, or a holograph of the consciousness of a dead girl. “Mother” is the AI security system that controls Jungle House, the Morel family’s vacation home in a country that resembles Colombia, where Pachico grew up and set her first two books. Lena, as the human caretaker, is forever grateful to Mother for rescuing her as a baby after the violent death of her parents, who were presumed rebels.

Pachico’s third novel is closer to sci-fi than I might have expected. Apart from Lena, the protagonist, all the major characters are machines or digital recreations: AI, droids, a drone, or a holograph of the consciousness of a dead girl. “Mother” is the AI security system that controls Jungle House, the Morel family’s vacation home in a country that resembles Colombia, where Pachico grew up and set her first two books. Lena, as the human caretaker, is forever grateful to Mother for rescuing her as a baby after the violent death of her parents, who were presumed rebels.

Mother is exacting but mercurial, strict about cleanliness yet apt to forget or overlook things during one of her “spells.” Lena pushes the boundaries of her independence, believing that Mother only wants to protect her but still longing to explore the degraded wilderness beyond the compound.

Mother was right, because Mother was always right about these kinds of things. The world was a complicated place, and Mother understood it much better than she did.

In the house, there was no privacy. In the house, Mother saw all.

Mother was Lena’s world. And Lena, in turn, was hers. No matter how angry they got at each other, no matter how much they fought, no matter the things that Mother did or didn’t do … they had each other.

It takes a while to work out just how tech-reliant this scenario is, what the repeated references to “the pit bull” are about, and how Lena emulated and resented Isabella, the Morel daughter, in equal measure. Even creepier than the satellites’ plan to digitize humans is the fact that Isabella’s security drone, Anton, can fabricate recorded memories. This reminded me a lot of Klara and the Sun. Tech themes aren’t my favourite, but I ultimately thought of this as an allegory of life with a narcissistic mother and the child’s essential task of breaking free. It’s not clinical and contrived, though; it’s a taut, subtle thriller with an evocative setting. (Public library)

See also: “Three on a Theme: Matrescence Memoirs”

Does one or more of these books take your fancy?

This is the middle of a trio of stories about Maya. They’re not in a row and I read the book over quite a number of months, so I was in danger of forgetting that we’d met this set of characters before. In the first, the title story, Maya has been with Rhodes for five years but is thinking of leaving him – and not just because she’s crushing on her boss. A health crisis with her dog leads her to rethink. In “Grendel’s Mother,” Maya is pregnant and hoping that she and her partner are on the same page.

This is the middle of a trio of stories about Maya. They’re not in a row and I read the book over quite a number of months, so I was in danger of forgetting that we’d met this set of characters before. In the first, the title story, Maya has been with Rhodes for five years but is thinking of leaving him – and not just because she’s crushing on her boss. A health crisis with her dog leads her to rethink. In “Grendel’s Mother,” Maya is pregnant and hoping that she and her partner are on the same page. I’ve had a mixed experience with Mackay, but the one novel of hers I got on well with, The Orchard on Fire, also dwells on the shattered innocence of childhood. By contrast, most of the stories in this collection are grimy ones about lonely older people – especially elderly women – reminding me of Barbara Comyns or Barbara Pym at her darkest. “Where the Carpet Ends,” about the long-term residents of a shabby hotel, recalls

I’ve had a mixed experience with Mackay, but the one novel of hers I got on well with, The Orchard on Fire, also dwells on the shattered innocence of childhood. By contrast, most of the stories in this collection are grimy ones about lonely older people – especially elderly women – reminding me of Barbara Comyns or Barbara Pym at her darkest. “Where the Carpet Ends,” about the long-term residents of a shabby hotel, recalls  Of course, I also loved “The Cat,” which Eleanor mentioned when she read my review of Matt Haig’s

Of course, I also loved “The Cat,” which Eleanor mentioned when she read my review of Matt Haig’s

The Emma Press has published poetry pamphlets before, but this is their inaugural full-length work. Rachel Spence’s second collection is in two parts: first is “Call & Response,” a sonnet sequence structured as a play and considering her relationship with her mother. Act 1 starts in 1976 and zooms forward to key moments when they fell out and then reversed their estrangement. The next section finds them in the new roles of patient and carer. “Your final check-up. August. Nimbus clouds / prised open by Delft blue. Waiting is hard.” In Act 3, death is near; “in that quantum hinge, we made / an alphabet from love’s ungrammared stutter.” The poems of the last act are dated precisely, not just to a month and year as earlier but down to the very day, hour and minute. Whether in Ludlow or Venice, Spence crystallizes moments from the ongoingness of grief, drawing images from the natural world.

The Emma Press has published poetry pamphlets before, but this is their inaugural full-length work. Rachel Spence’s second collection is in two parts: first is “Call & Response,” a sonnet sequence structured as a play and considering her relationship with her mother. Act 1 starts in 1976 and zooms forward to key moments when they fell out and then reversed their estrangement. The next section finds them in the new roles of patient and carer. “Your final check-up. August. Nimbus clouds / prised open by Delft blue. Waiting is hard.” In Act 3, death is near; “in that quantum hinge, we made / an alphabet from love’s ungrammared stutter.” The poems of the last act are dated precisely, not just to a month and year as earlier but down to the very day, hour and minute. Whether in Ludlow or Venice, Spence crystallizes moments from the ongoingness of grief, drawing images from the natural world. Not only the pun-tastic title, but also the excellent nominative determinism of chef and food historian Dr Neil Buttery’s name, earned this a place in my

Not only the pun-tastic title, but also the excellent nominative determinism of chef and food historian Dr Neil Buttery’s name, earned this a place in my  Foust’s fifth collection – at 41 pages, the length of a long chapbook – is in conversation with the language and storyline of 1984. George Orwell’s classic took on new prescience for her during Donald Trump’s first presidential term, a period marked by a pandemic as well as by corruption, doublespeak and violence. “Rally

Foust’s fifth collection – at 41 pages, the length of a long chapbook – is in conversation with the language and storyline of 1984. George Orwell’s classic took on new prescience for her during Donald Trump’s first presidential term, a period marked by a pandemic as well as by corruption, doublespeak and violence. “Rally  I’d been vaguely attracted by descriptions of the Spanish poet’s novels Permafrost and Boulder, which are also about lesbians in odd situations. Mammoth is the third book in a loose trilogy. Its 24-year-old narrator is so desperate for a baby that she’s decided to have unprotected sex with men until a pregnancy results. In the meantime, her sociology project at nursing homes comes to an end and she moves from Barcelona to a remote farm where she develops subsistence skills and forms an interdependent relationship with the gruff shepherd. “I’d been living in a drowning city, and I need this – the restorative silence of a decompression chamber. … my past is meaningless, and yet here, in this place, there is someone else’s past that I can set up and live in awhile.” For me this was a peculiar combination of distinguished writing (“The city pounces on the still-pale light emerging from the deep sea and seizes it with its lucrative forceps”) but absolutely repellent story, with a protagonist whose every decision makes you want to throttle her. An extended scene of exterminating feral cats certainly didn’t help matters. I’d be wary of trying Baltasar again.

I’d been vaguely attracted by descriptions of the Spanish poet’s novels Permafrost and Boulder, which are also about lesbians in odd situations. Mammoth is the third book in a loose trilogy. Its 24-year-old narrator is so desperate for a baby that she’s decided to have unprotected sex with men until a pregnancy results. In the meantime, her sociology project at nursing homes comes to an end and she moves from Barcelona to a remote farm where she develops subsistence skills and forms an interdependent relationship with the gruff shepherd. “I’d been living in a drowning city, and I need this – the restorative silence of a decompression chamber. … my past is meaningless, and yet here, in this place, there is someone else’s past that I can set up and live in awhile.” For me this was a peculiar combination of distinguished writing (“The city pounces on the still-pale light emerging from the deep sea and seizes it with its lucrative forceps”) but absolutely repellent story, with a protagonist whose every decision makes you want to throttle her. An extended scene of exterminating feral cats certainly didn’t help matters. I’d be wary of trying Baltasar again. At age 39, divorced interior decorator Paule is “passionately concerned with her beauty and battling with the transition from young to youngish woman”. (Ouch. But true.) It’s an open secret that her partner Roger is always engaged in a liaison with a young woman; people pity her and scorn Roger for his infidelity. But when Paule has a dalliance with a client’s son, 25-year-old lawyer Simon, a double standard emerges: “they had never shown her the mixture of contempt and envy she was going to arouse this time.” Simon is an idealist, accusing her of “letting love go by, of neglecting your duty to be happy”, but he’s also indolent and too fond of drink. Paule wonders if she’s expected too much from an affair. “Everyone advised a change of air, and she thought sadly that all she was getting was a change of lovers: less bother, more Parisian, so common”.

At age 39, divorced interior decorator Paule is “passionately concerned with her beauty and battling with the transition from young to youngish woman”. (Ouch. But true.) It’s an open secret that her partner Roger is always engaged in a liaison with a young woman; people pity her and scorn Roger for his infidelity. But when Paule has a dalliance with a client’s son, 25-year-old lawyer Simon, a double standard emerges: “they had never shown her the mixture of contempt and envy she was going to arouse this time.” Simon is an idealist, accusing her of “letting love go by, of neglecting your duty to be happy”, but he’s also indolent and too fond of drink. Paule wonders if she’s expected too much from an affair. “Everyone advised a change of air, and she thought sadly that all she was getting was a change of lovers: less bother, more Parisian, so common”.