Six Degrees of Separation: Romantic Comedy to Wild Fell

This is a fun meme I take part in every few months.

For August we begin with Romantic Comedy by Curtis Sittenfeld, one of my top 2023 releases so far. (See Kate’s opening post.)

#1 Sittenfeld’s protagonist, Sally Milz, writes TV comedy, as does Kristin Newman (That ’70s Show, How I Met Your Mother, etc.), author of What I Was Doing While You Were Breeding, a lighthearted record of her travels and romantic conquests. (She even has a passage that reminds me of Sally’s Danny Horst Rule: “I looked like a thirty-year-old writer. Not like a twenty-year-old model or actress or epically legged songstress, which is a category into which an alarmingly high percentage of Angelenas fall. And, because the city is so lousy with these leggy aliens, regular- to below-average-looking guys with reasonable employment levels can actually get one, another maddening aspect of being a woman in this city.”)

#1 Sittenfeld’s protagonist, Sally Milz, writes TV comedy, as does Kristin Newman (That ’70s Show, How I Met Your Mother, etc.), author of What I Was Doing While You Were Breeding, a lighthearted record of her travels and romantic conquests. (She even has a passage that reminds me of Sally’s Danny Horst Rule: “I looked like a thirty-year-old writer. Not like a twenty-year-old model or actress or epically legged songstress, which is a category into which an alarmingly high percentage of Angelenas fall. And, because the city is so lousy with these leggy aliens, regular- to below-average-looking guys with reasonable employment levels can actually get one, another maddening aspect of being a woman in this city.”)

#2 I didn’t realize when I picked it up in a charity shop that my copy smelled strongly of cigarette smoke. I aired it in kitty litter, then by scented candles, and it still reeks. I reckon I can tolerate the smell long enough to finish it and put it in the Little Free Library, which gets good ventilation. A novel I acquired from the free bookshop we used to have in the mall in town was the only book I can remember having to get rid of before reading because it just smelled too bad (also of cigarettes in that case): My Sister’s Keeper by Jodi Picoult.

#2 I didn’t realize when I picked it up in a charity shop that my copy smelled strongly of cigarette smoke. I aired it in kitty litter, then by scented candles, and it still reeks. I reckon I can tolerate the smell long enough to finish it and put it in the Little Free Library, which gets good ventilation. A novel I acquired from the free bookshop we used to have in the mall in town was the only book I can remember having to get rid of before reading because it just smelled too bad (also of cigarettes in that case): My Sister’s Keeper by Jodi Picoult.

#3 So I didn’t read that, but I have read another Picoult novel, Sing You Home. The author is known for picking a central issue to address in each work, and in that one it was sexuality. Zoe, a music therapist, is married to Max but leaves him for Vanessa – and then decides to sue him for the use of the embryos they created together via IVF. It was the first book I’d read with that dynamic (a previously straight woman enters into a lesbian partnership), but by no means the last. Later came Untamed by Glennon Doyle, Hidden Nature by Alys Fowler, The Fixed Stars by Molly Wizenberg … and one you maybe weren’t expecting: the fantastic memoir First Time Ever by Peggy Seeger. The authors vary in how they account for it. They were gay all along but didn’t realize it? Their orientation changed? Or they just happened to fall in love with someone of the same gender? Seeger doesn’t explain at all, simply records how head-over-heels she was for Ewan MacColl … and then for Irene Pyper Scott.

#3 So I didn’t read that, but I have read another Picoult novel, Sing You Home. The author is known for picking a central issue to address in each work, and in that one it was sexuality. Zoe, a music therapist, is married to Max but leaves him for Vanessa – and then decides to sue him for the use of the embryos they created together via IVF. It was the first book I’d read with that dynamic (a previously straight woman enters into a lesbian partnership), but by no means the last. Later came Untamed by Glennon Doyle, Hidden Nature by Alys Fowler, The Fixed Stars by Molly Wizenberg … and one you maybe weren’t expecting: the fantastic memoir First Time Ever by Peggy Seeger. The authors vary in how they account for it. They were gay all along but didn’t realize it? Their orientation changed? Or they just happened to fall in love with someone of the same gender? Seeger doesn’t explain at all, simply records how head-over-heels she was for Ewan MacColl … and then for Irene Pyper Scott.

#4 Peggy Seeger is one of my heroes these days. I first got into her music through the lockdown livestreams put together by Folk on Foot and have since seen her live and acquired several of her albums, including a Smithsonian Folkways collection of her best-loved folk standards. One of these is, of course, “I’m Gonna Be an Engineer,” which was one of the inspirations for Claire Fuller’s Unsettled Ground.

#4 Peggy Seeger is one of my heroes these days. I first got into her music through the lockdown livestreams put together by Folk on Foot and have since seen her live and acquired several of her albums, including a Smithsonian Folkways collection of her best-loved folk standards. One of these is, of course, “I’m Gonna Be an Engineer,” which was one of the inspirations for Claire Fuller’s Unsettled Ground.

#5 Unsettled Ground, an unusual story of rural poverty and illiteracy, is set in a fictional village modelled on Inkpen, where Nicola Chester lives. Her memoir On Gallows Down, which held particular local interest for me, was shortlisted for the Wainwright Prize last year.

#5 Unsettled Ground, an unusual story of rural poverty and illiteracy, is set in a fictional village modelled on Inkpen, where Nicola Chester lives. Her memoir On Gallows Down, which held particular local interest for me, was shortlisted for the Wainwright Prize last year.

#6 Also shortlisted that year was Wild Fell by Lee Schofield, about his work at RSPB Haweswater. Like Chester, he’s been mired in the struggle to balance sustainable farming with conservation at a beloved place. And like a fellow Lakeland farmer (and previous Wainwright Prize winner for English Pastoral), James Rebanks, he’s trying to be respectful of tradition while also restoring valuable habitats. My husband and I each took a library copy of Wild Fell along to Cumbria last week (about which more anon) and packed it in a backpack for an on-location photo during our wild walk at the very atmospheric Haweswater.

#6 Also shortlisted that year was Wild Fell by Lee Schofield, about his work at RSPB Haweswater. Like Chester, he’s been mired in the struggle to balance sustainable farming with conservation at a beloved place. And like a fellow Lakeland farmer (and previous Wainwright Prize winner for English Pastoral), James Rebanks, he’s trying to be respectful of tradition while also restoring valuable habitats. My husband and I each took a library copy of Wild Fell along to Cumbria last week (about which more anon) and packed it in a backpack for an on-location photo during our wild walk at the very atmospheric Haweswater.

Where will your chain take you? Join us for #6Degrees of Separation! (Hosted on the first Saturday of each month by Kate W. of Books Are My Favourite and Best.) Next month’s starting book is Wifedom by Anna Funder.

Have you read any of my selections? Tempted by any you didn’t know before?

Bill Bryson’s Notes from a Small Island: Reread and Stage Production

Bill Bryson, an American author of humorous travel and popular history or science books, is considered a national treasure in his adopted Great Britain. He is a particular favourite of my husband and in-laws, who got me into his work back in the early to mid-2000s. As I, too, was falling in love with the country, I found much to relate to in his travel-based memoirs of expatriate life and temporary returns to the USA. Sometimes it takes an outsider’s perspective to see things clearly.

When we heard that Notes from a Small Island (1995), his account of a valedictory tour around Britain before returning to live in the States for the first time in 20 years, had been adapted into a play by Tim Whitnall and would be performed at our local theatre, the Watermill, we thought, huh, it never would have occurred to us to put this particular book on stage. Would it work? we wondered. The answer is yes and no, but it was entertaining and we were glad that we went. We presented tickets as my in-laws’ Christmas present and accompanied them to a mid-February matinee before supper at ours.

When we heard that Notes from a Small Island (1995), his account of a valedictory tour around Britain before returning to live in the States for the first time in 20 years, had been adapted into a play by Tim Whitnall and would be performed at our local theatre, the Watermill, we thought, huh, it never would have occurred to us to put this particular book on stage. Would it work? we wondered. The answer is yes and no, but it was entertaining and we were glad that we went. We presented tickets as my in-laws’ Christmas present and accompanied them to a mid-February matinee before supper at ours.

A few members of my book club decided to see the show later in the run and suggested we read – or reread, as was the case for several of us – the book in March. I started my reread before attending the play and had gotten through the first 50 pages, which is mostly about his first visit to England in 1973 (including a stay in a Dover boarding-house presided over by the infamously officious “Mrs Smegma”). This was ideal as the first bit contains the funniest stuff and, with the addition of some autobiographical material from later in the book plus his 2006 memoir The Life and Times of the Thunderbolt Kid, made up the entirety of the first act.

Photos are screenshots from the Watermill website.

Bryson traveled almost exclusively by public transport, so the set had the brick and steel walls of a generic terminal, and a bus shelter and benches were brought into service as the furnishing for most scenes. The problem with frontloading the play with hilarious scenes is that the second act, like the book itself on this reread, became rather a slog of random stops, acerbic observations, finding somewhere to stay and something to eat (often curry), and then doing it all over again.

Mark Hadfield, in the starring role, had the unenviable role of carrying the action and remembering great swathes of text lifted directly from the book. That’s all well and good as a strategy for giving a flavour of the writing style, but the language needed to be simplified; the poor man couldn’t cope and kept fluffing his lines. There were attempts to ease the burden: sections were read out by other characters in the form of announcements, letters or postcards; some reflections were played as if from Bryson’s Dictaphone. It was best, though, when there were scenes rather than monologues against a projected map, because there was an excellent ensemble cast of six who took on the various bit parts and these were often key occasions for humour: hotel-keepers, train-spotters, unintelligible accents in a Glasgow pub.

The trajectory was vaguely southeast to northwest – as far as John O’Groats, then back home to the Yorkshire Dales – but the actual route was erratic, based on whimsy as much as the availability of trains and buses. Bryson sings the praises of places like Salisbury and Durham and the pinnacles of coastal walks, and slates others, including some cities, seaside resorts and tourist traps. Places of personal significance make it onto his itinerary, such as the former mental asylum at Virginia Water, Surrey where he worked and met his wife in the 1970s. (My husband and I lived across the street from it for a year and a half.) He’s grumpy about having to pay admission fees that in today’s money sound minimal – £2.80 for Stonehenge!

The main interest for me in both book and play was the layers of recent history: the nostalgia for the old-fashioned country he discovered at a pivotal time in his own young life in the 1970s; the disappointments but still overall optimism of the 1990s; and the hindsight the reader or viewer brings to the material today. At a time when workers of every type seem to be on strike, it was poignant to read about the protests against Margaret Thatcher and the protracted printers’ strike of the 1980s.

The main interest for me in both book and play was the layers of recent history: the nostalgia for the old-fashioned country he discovered at a pivotal time in his own young life in the 1970s; the disappointments but still overall optimism of the 1990s; and the hindsight the reader or viewer brings to the material today. At a time when workers of every type seem to be on strike, it was poignant to read about the protests against Margaret Thatcher and the protracted printers’ strike of the 1980s.

The central message of the book, that Britain has an amazing heritage that it doesn’t adequately appreciate and is rapidly losing to homogenization, still holds. Yet I’m not sure the points about the at-heart goodness and politeness of the happy-with-their-lot British remain true. Is it just me or have general entitlement, frustration, rage and nastiness taken over? Not as notable as in the USA, but social divisions and the polarization of opinions are getting worse here, too. One can’t help but wonder what the picture would have been post-Brexit as well. Bryson wrote a sort-of sequel in 2015, The Road to Little Dribbling, in which the sarcasm and curmudgeonly persona override the warmth and affection of the earlier book.

The central message of the book, that Britain has an amazing heritage that it doesn’t adequately appreciate and is rapidly losing to homogenization, still holds. Yet I’m not sure the points about the at-heart goodness and politeness of the happy-with-their-lot British remain true. Is it just me or have general entitlement, frustration, rage and nastiness taken over? Not as notable as in the USA, but social divisions and the polarization of opinions are getting worse here, too. One can’t help but wonder what the picture would have been post-Brexit as well. Bryson wrote a sort-of sequel in 2015, The Road to Little Dribbling, in which the sarcasm and curmudgeonly persona override the warmth and affection of the earlier book.

Indeed, my book club noted that a lot of the jokes were things he couldn’t get away with saying today, and the theatre issued a content warning: “This production includes the use of very strong language, language reflective of historical attitudes around Mental Health, reference to drug use, sexual references, mention of suicide, flashing lights, pyrotechnics, loud sound effect explosions, and haze. This production is most suitable for those aged 12+.”

So, yes, an amusing journey, but a bittersweet one to revisit, and an odd choice for the stage.

A favourite line I’ll leave you with: “To this day, I remain impressed by the ability of Britons of all ages and social backgrounds to get genuinely excited by the prospect of a hot beverage.”

Book:

Original rating (c. 2004):

My rating now:

Play:

Have you read anything by Bill Bryson? Are you a fan?

February Releases by Nick Acheson, Charlotte Eichler and Nona Fernández (#ReadIndies)

Three final selections for Read Indies. I’m pleased to have featured 16 books from independent publishers this month. And how’s this for neat symmetry? I started the month with Chase of the Wild Goose and finish with a literal wild goose chase as Nick Acheson tracks down Norfolk’s flocks in the lockdown winter of 2020–21. Also appearing today are nature- and travel-filled poems and a hybrid memoir about Chilean and family history.

The Meaning of Geese: A thousand miles in search of home by Nick Acheson

I saw Nick Acheson speak at New Networks for Nature 2021 as the ‘anti-’ voice in a debate on ecotourism. He was a wildlife guide in South America and Africa for more than a decade before, waking up to the enormity of the climate crisis, he vowed never to fly again. Now he mostly stays close to home in North Norfolk, where he grew up and where generations of his family have lived and farmed, working for Norfolk Wildlife Trust and appreciating the flora and fauna on his doorstep.

This was indeed to be a low-carbon initiative, undertaken on his mother’s 40-year-old red bicycle and spanning September 2021 to the start of the following spring. Whether on his own or with friends and experts, and in fair weather or foul, he became obsessed with spending as much time observing geese as he could – even six hours at a stretch. Pink-footed geese descend on the Holkham Estate in their thousands, but there were smaller flocks and rarer types as well: from Canada and greylag to white-fronted and snow geese. He also found perspective (historical, ethical and geographical) by way of Peter Scott’s conservation efforts, chats with hunters, and insight from the Icelandic researchers who watch the geese later in the year, after they leave the UK. The germane context is woven into a month-by-month diary.

This was indeed to be a low-carbon initiative, undertaken on his mother’s 40-year-old red bicycle and spanning September 2021 to the start of the following spring. Whether on his own or with friends and experts, and in fair weather or foul, he became obsessed with spending as much time observing geese as he could – even six hours at a stretch. Pink-footed geese descend on the Holkham Estate in their thousands, but there were smaller flocks and rarer types as well: from Canada and greylag to white-fronted and snow geese. He also found perspective (historical, ethical and geographical) by way of Peter Scott’s conservation efforts, chats with hunters, and insight from the Icelandic researchers who watch the geese later in the year, after they leave the UK. The germane context is woven into a month-by-month diary.

The Covid-19 lockdowns spawned a number of nature books in the UK – for instance, I’ve also read Goshawk Summer by James Aldred, Birdsong in a Time of Silence by Steven Lovatt, The Consolation of Nature by Michael McCarthy, Jeremy Mynott and Peter Marren, and Skylarks with Rosie by Stephen Moss – and although the pandemic is not a major element here, one does get a sense of how Acheson struggled with isolation as well as the normal winter blues and found comfort and purpose in birdwatching.

Tundra bean, taiga bean, brent … I don’t think I’ve seen any of these species – not even pinkfeet, to my recollection – so wished for black-and-white drawings or colour photographs in the book. That’s not to say that Acheson is not successful at painting word pictures of geese; his rich descriptions, full of food-related and sartorial metaphors, are proof of how much he revels in the company of birds. But I suspect this is a book more for birders than for casual nature-watchers like myself. I would have welcomed more autobiographical material, and Wintering by Stephen Rutt seems the more suitable geese book for laymen. Still, I admire Acheson’s fervour: “I watch birds not to add them to a list of species seen; nor to sneer at birds which are not truly wild. I watch them because they are magnificent”.

With thanks to Chelsea Green Publishing for the free copy for review.

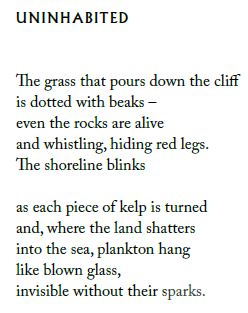

Swimming Between Islands by Charlotte Eichler

Eichler’s debut collection was inspired by various trips to cold and remote places, such as to Lofoten 10 years ago, as she explains in a blog post on the Carcanet website. (The cover image is her painting Nusfjord.) British and Scandinavian islands and their wildlife provide much of the imagery and atmosphere. You can sink into the moss and fog, lulled by alliteration. A glance at some of the poem titles reveals the breadth of her gaze: “Brimstones” – “A Pheasant” (a perfect description in just two lines) – “A Meditation of Small Frogs” – “Trapping Moths with My Father.” There are also historical vignettes and pen portraits. The scenes of childhood, as in the four-part “What Little Girls Are Made Of,” evoke the freedom of curiosity about the natural world and feel autobiographical yet universal.

Eichler’s debut collection was inspired by various trips to cold and remote places, such as to Lofoten 10 years ago, as she explains in a blog post on the Carcanet website. (The cover image is her painting Nusfjord.) British and Scandinavian islands and their wildlife provide much of the imagery and atmosphere. You can sink into the moss and fog, lulled by alliteration. A glance at some of the poem titles reveals the breadth of her gaze: “Brimstones” – “A Pheasant” (a perfect description in just two lines) – “A Meditation of Small Frogs” – “Trapping Moths with My Father.” There are also historical vignettes and pen portraits. The scenes of childhood, as in the four-part “What Little Girls Are Made Of,” evoke the freedom of curiosity about the natural world and feel autobiographical yet universal.

With thanks to Carcanet Press for the free copy for review.

Voyager: Constellations of Memory—A Memoir by Nona Fernández (2019; 2023)

[Translated from the Spanish by Natasha Wimmer]

Our archive of memories is the closest thing we have to a record of identity. … Disjointed fragments, a pile of mirror shards, a heap of the past. The accumulation is what we’re made of.

When Fernández’s elderly mother started fainting and struggling with recall, it prompted the Chilean actress and writer to embark on an inquiry into memory. Astronomy provides the symbolic language here, with memory a constellation and gaps as black holes. But the stars also play a literal role. Fernández was part of an Amnesty International campaign to rename a constellation in honour of the 26 people “disappeared” in Chile’s Atacama Desert in 1973. She meets the widow of one of the victims, wondering what he might have been like as an older man as she helps to plan the star ceremony. This oblique and imaginative narrative ties together brain evolution, a medieval astronomer executed for heresy, Pinochet administration collaborators, her son’s birth, and her mother’s surprise 80th birthday party. NASA’s Voyager probes, launched in 1977, were intended as time capsules capturing something of human life at the time. The author imagines her brief memoir doing the same: “A book is a space-time capsule. It freezes the present and launches it into tomorrow as a message.”

When Fernández’s elderly mother started fainting and struggling with recall, it prompted the Chilean actress and writer to embark on an inquiry into memory. Astronomy provides the symbolic language here, with memory a constellation and gaps as black holes. But the stars also play a literal role. Fernández was part of an Amnesty International campaign to rename a constellation in honour of the 26 people “disappeared” in Chile’s Atacama Desert in 1973. She meets the widow of one of the victims, wondering what he might have been like as an older man as she helps to plan the star ceremony. This oblique and imaginative narrative ties together brain evolution, a medieval astronomer executed for heresy, Pinochet administration collaborators, her son’s birth, and her mother’s surprise 80th birthday party. NASA’s Voyager probes, launched in 1977, were intended as time capsules capturing something of human life at the time. The author imagines her brief memoir doing the same: “A book is a space-time capsule. It freezes the present and launches it into tomorrow as a message.”

With thanks to Daunt Books for the free copy for review.

Six Degrees of Separation: From Ruth Ozeki to Ruth Padel

This month we begin with The Book of Form and Emptiness by Ruth Ozeki, which recently won the Women’s Prize for Fiction. It happens to be my least favourite of her books that I’ve read so far, but I was pleased to see her work recognised nonetheless. (See also Kate’s opening post.)

#1 One of the peripheral characters in Ozeki’s novel is an Eastern European philosopher who goes by “The Bottleman.” I had to wonder if he was based on avant-garde Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Žižek. Back in 2010, when I was working at a university library in London and had access to nearly any book I could think of – and was still committed to trying to read the sorts of books I thought I should enjoy rather than what I actually did – I skimmed a couple of Žižek’s works, including First as Tragedy, Then as Farce (2009), which arose from 9/11 and the global financial crisis and questions whether we can ever stop history repeating itself without undermining capitalism.

#1 One of the peripheral characters in Ozeki’s novel is an Eastern European philosopher who goes by “The Bottleman.” I had to wonder if he was based on avant-garde Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Žižek. Back in 2010, when I was working at a university library in London and had access to nearly any book I could think of – and was still committed to trying to read the sorts of books I thought I should enjoy rather than what I actually did – I skimmed a couple of Žižek’s works, including First as Tragedy, Then as Farce (2009), which arose from 9/11 and the global financial crisis and questions whether we can ever stop history repeating itself without undermining capitalism.

#2 In searching my archives for farces I’ve read, I came across one I took notes on but never wrote up back in 2013: Japanese by Spring by Ishmael Reed (1993), an academic comedy set at “Jack London College” in Oakland, California. The novel satirizes almost every ideology prevalent in the 1960s–80s: multiculturalism, racism, xenophobia, nationalism, feminism, affirmative action and various literary critical methods. Reed sets up exaggerated and polarized groups and opinions. (You know it’s not to be taken entirely seriously when you see character names like Chappie Puttbutt, President Stool and Professor Poop, short for Poopovich.) The college is sold off to the Japanese and Ishmael Reed himself becomes a character. There are some amusing lines but I ended up concluding that Reed wasn’t for me. If you’ve enjoyed work by Paul Beatty and Percival Everett, he might be up your street.

#2 In searching my archives for farces I’ve read, I came across one I took notes on but never wrote up back in 2013: Japanese by Spring by Ishmael Reed (1993), an academic comedy set at “Jack London College” in Oakland, California. The novel satirizes almost every ideology prevalent in the 1960s–80s: multiculturalism, racism, xenophobia, nationalism, feminism, affirmative action and various literary critical methods. Reed sets up exaggerated and polarized groups and opinions. (You know it’s not to be taken entirely seriously when you see character names like Chappie Puttbutt, President Stool and Professor Poop, short for Poopovich.) The college is sold off to the Japanese and Ishmael Reed himself becomes a character. There are some amusing lines but I ended up concluding that Reed wasn’t for me. If you’ve enjoyed work by Paul Beatty and Percival Everett, he might be up your street.

#3 “Call me Ishmael” – even if, like me, you have never gotten through Moby-Dick by Herman Melville (1851), you probably know that famous opening line. I took an entire course on Nathaniel Hawthorne and Melville as an undergraduate and still didn’t manage to read the whole thing! Even my professor acknowledged that Melville could have done with a really good editor to rein in his ideas and cut out some of his digressions.

#3 “Call me Ishmael” – even if, like me, you have never gotten through Moby-Dick by Herman Melville (1851), you probably know that famous opening line. I took an entire course on Nathaniel Hawthorne and Melville as an undergraduate and still didn’t manage to read the whole thing! Even my professor acknowledged that Melville could have done with a really good editor to rein in his ideas and cut out some of his digressions.

#4 A favourite that I can recommend instead is Moby-Duck by Donovan Hohn (2011). It’s just the kind of random, wide-ranging nonfiction I love: part memoir, part travelogue, part philosophical musing on human culture and our impact on the environment. In 1992 a pallet of “Friendly Floatees” bath toys fell off a container ship in a storm in the North Pacific. Over the next two decades those thousands of plastic animals made their way around the world, informing oceanographic theory and delighting children. Hohn’s obsessive quest for the origin of the bath toys and the details of their high seas journey takes on the momentousness of his literary antecedent. He visits a Chinese factory and sees plastics being made; he volunteers on a beach-cleaning mission in Alaska. (I’d not seen the Ozeki cover that appears in Kate’s post, but how pleasing to note that it also has a rubber duck on it!)

#4 A favourite that I can recommend instead is Moby-Duck by Donovan Hohn (2011). It’s just the kind of random, wide-ranging nonfiction I love: part memoir, part travelogue, part philosophical musing on human culture and our impact on the environment. In 1992 a pallet of “Friendly Floatees” bath toys fell off a container ship in a storm in the North Pacific. Over the next two decades those thousands of plastic animals made their way around the world, informing oceanographic theory and delighting children. Hohn’s obsessive quest for the origin of the bath toys and the details of their high seas journey takes on the momentousness of his literary antecedent. He visits a Chinese factory and sees plastics being made; he volunteers on a beach-cleaning mission in Alaska. (I’d not seen the Ozeki cover that appears in Kate’s post, but how pleasing to note that it also has a rubber duck on it!)

#5 Alongside Moby-Duck on my “uncategorizable” Goodreads shelf is The Snow Leopard by Peter Matthiessen (1978), one of my Books of Summer from 2019. A nature/travel classic that turns into something more like a spiritual memoir, it’s about a trip to Nepal in 1973, with Matthiessen joining a zoologist to study Himalayan blue sheep – and hoping to spot the elusive snow leopard. He had recently lost his partner to cancer, and relied on his Buddhist training to remind himself of tenets of acceptance and transience.

#5 Alongside Moby-Duck on my “uncategorizable” Goodreads shelf is The Snow Leopard by Peter Matthiessen (1978), one of my Books of Summer from 2019. A nature/travel classic that turns into something more like a spiritual memoir, it’s about a trip to Nepal in 1973, with Matthiessen joining a zoologist to study Himalayan blue sheep – and hoping to spot the elusive snow leopard. He had recently lost his partner to cancer, and relied on his Buddhist training to remind himself of tenets of acceptance and transience.

#6 Ruth Padel is one of my favourite contemporary poets and a fixture at the New Networks for Nature conference I attend each year. She has a collection named The Soho Leopard (2004), whose title sequence is about urban foxes. The natural world and her travels are always a major element of her books. From one Ruth to another, then, by way of philosophy, farce, whaling, rubber ducks and mountain adventuring.

#6 Ruth Padel is one of my favourite contemporary poets and a fixture at the New Networks for Nature conference I attend each year. She has a collection named The Soho Leopard (2004), whose title sequence is about urban foxes. The natural world and her travels are always a major element of her books. From one Ruth to another, then, by way of philosophy, farce, whaling, rubber ducks and mountain adventuring.

Where will your chain take you? Join us for #6Degrees of Separation! (Hosted on the first Saturday of each month by Kate W. of Books Are My Favourite and Best.) Next month’s starting point is a wildcard: use the book you finished with this month (or, if you haven’t done an August chain, the last book you’ve read).

Have you read any of my selections? Tempted by any you didn’t know before?

Six Degrees of Separation: From Wintering to The Summer of the Bear

This month we begin with Wintering by Katherine May. I reviewed this for the Times Literary Supplement back in early 2020 and enjoyed the blend of memoir, nature and travel writing. (See also Kate’s opening post.)

#1 May travels to Iceland, which is the location of Sarah Moss’s memoir Names for the Sea. I’ve read nine of Moss’s books and consider her one of my favourite contemporary authors. (I’m currently rereading Night Waking.)

#1 May travels to Iceland, which is the location of Sarah Moss’s memoir Names for the Sea. I’ve read nine of Moss’s books and consider her one of my favourite contemporary authors. (I’m currently rereading Night Waking.)

#2 Nancy Campbell’s Fifty Words for Snow shares an interest in languages and naming. I noted that the Icelandic “hundslappadrifa” refers to snowflakes as large as a dog’s paw.

#2 Nancy Campbell’s Fifty Words for Snow shares an interest in languages and naming. I noted that the Icelandic “hundslappadrifa” refers to snowflakes as large as a dog’s paw.

#3 In 2018–19, Campbell was the poet laureate for the Canal & River Trust. As part of her tour of the country’s waterways, she came to Newbury and wrote a poem on commission about the community gardening project I volunteer with. (Here’s her blog post about the experience.) Three Women and a Boat by Anne Youngson is about a canalboat journey.

#3 In 2018–19, Campbell was the poet laureate for the Canal & River Trust. As part of her tour of the country’s waterways, she came to Newbury and wrote a poem on commission about the community gardening project I volunteer with. (Here’s her blog post about the experience.) Three Women and a Boat by Anne Youngson is about a canalboat journey.

#4 Youngson’s novel was inspired by the setup of Jerome K. Jerome’s Three Men in a Boat. Another book loosely based on a classic is The Decameron Project, a set of 29 short stories ranging from realist to dystopian in their response to pandemic times.

#4 Youngson’s novel was inspired by the setup of Jerome K. Jerome’s Three Men in a Boat. Another book loosely based on a classic is The Decameron Project, a set of 29 short stories ranging from realist to dystopian in their response to pandemic times.

#5 Another project updating the classics was the Hogarth Shakespeare series. One of these books (though not my favourite) was The Gap of Time by Jeanette Winterson, her take on The Winter’s Tale.

#5 Another project updating the classics was the Hogarth Shakespeare series. One of these books (though not my favourite) was The Gap of Time by Jeanette Winterson, her take on The Winter’s Tale.

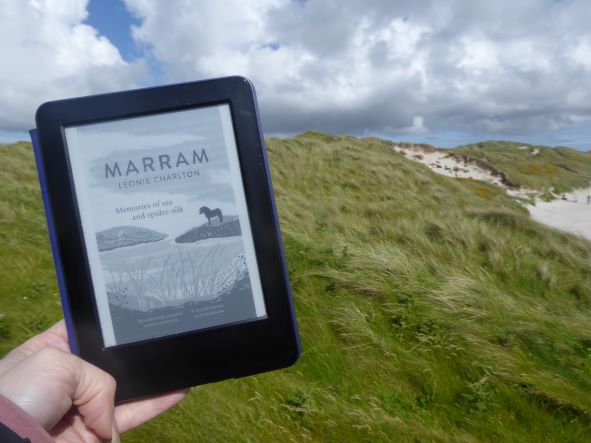

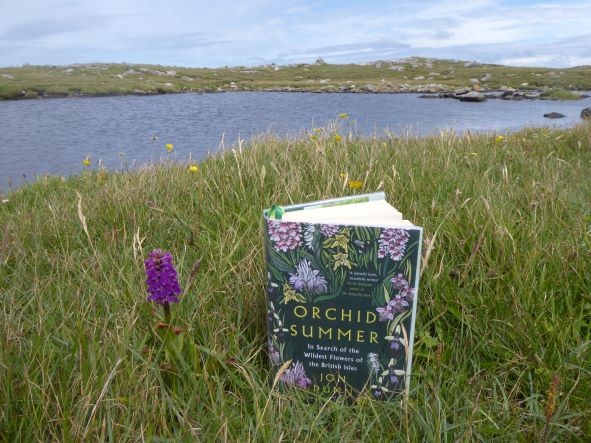

#6 Even if you’ve not read it (it happened to be on my undergraduate curriculum), you probably know that The Winter’s Tale famously includes the stage direction “Exit, pursued by a bear.” I’m finishing with The Summer of the Bear by Bella Pollen, one of the novels I read on my trip to the Outer Hebrides because it’s set on North Uist. I’ll review it in full soon, but for now will say that it does actually have a bear in it, and is based on a true story.

#6 Even if you’ve not read it (it happened to be on my undergraduate curriculum), you probably know that The Winter’s Tale famously includes the stage direction “Exit, pursued by a bear.” I’m finishing with The Summer of the Bear by Bella Pollen, one of the novels I read on my trip to the Outer Hebrides because it’s set on North Uist. I’ll review it in full soon, but for now will say that it does actually have a bear in it, and is based on a true story.

I’m pleased with myself for going from Wintering (via various other ice, snow and winter references) to a “Summer” title. We’ve crossed the hemispheres from Kate’s Australian winter to summertime here.

Where will your chain take you? Join us for #6Degrees of Separation! (Hosted on the first Saturday of each month by Kate W. of Books Are My Favourite and Best.) Next month’s starting point will be the recent winner of the Women’s Prize, The Book of Form and Emptiness by Ruth Ozeki.

Have you read any of my selections? Tempted by any you didn’t know before?

20 Books of Summer, 4–5: Roy Dennis & Sophie Pavelle

The next two entries in my flora-themed summer reading are books I read for paid reviews, so I only give extracts from my thoughts below. These are both UK-based environmentalist travel memoirs and counted because of their titles, but do also feature plants in the text. I have various relevant books of my own and from the library on the go toward this challenge. Despite the complications of a rail strike and two cancelled trains, we have persisted in finding workarounds and making new bookings, so our trip to the Outer Hebrides is going ahead – whew! I’ll schedule a few posts for while I’m away and hope to share all that was seen and done (and read) when I’m back in early July.

Mistletoe Winter: Essays of a Naturalist throughout the Year by Roy Dennis (2021)

Dennis is among the UK’s wildlife conservation pioneers, particularly active in reintroducing birds of prey such as ospreys and white-tailed eagles (see also my response to his Restoring the Wild). In this essay collection, his excitement about everyday encounters with the natural world matches his zeal for momentous rewilding projects. The book entices with the wonders that can be experienced through close attention, like the dozen species’ worth of tracks identified on a snowy morning’s walk. Dennis is sober about wildlife declines witnessed in his lifetime. Practical and plain-speaking, he does not shy away from bold proposals. However, some of the pieces feel slight or dated, and it’s unclear how relevant the specific case studies will prove elsewhere. (Full review forthcoming for Foreword Reviews.)

Dennis is among the UK’s wildlife conservation pioneers, particularly active in reintroducing birds of prey such as ospreys and white-tailed eagles (see also my response to his Restoring the Wild). In this essay collection, his excitement about everyday encounters with the natural world matches his zeal for momentous rewilding projects. The book entices with the wonders that can be experienced through close attention, like the dozen species’ worth of tracks identified on a snowy morning’s walk. Dennis is sober about wildlife declines witnessed in his lifetime. Practical and plain-speaking, he does not shy away from bold proposals. However, some of the pieces feel slight or dated, and it’s unclear how relevant the specific case studies will prove elsewhere. (Full review forthcoming for Foreword Reviews.)

Forget Me Not: Finding the forgotten species of climate-change Britain by Sophie Pavelle (2022)

A late-twenties science communicator for Beaver Trust, Pavelle is enthusiastic and self-deprecating. Her nature quest takes in insects like the marsh fritillary and bilberry bumblebee and marine species such as seagrass and the Atlantic salmon. Travelling between lockdowns in 2020–1, she takes low-carbon transport wherever possible and bolsters her trip accounts with context, much of it gleaned from Zoom calls and e-mail correspondence with experts from museums and universities. Refreshingly, half the interviewees are women, and her animal subjects are never obvious choices. The snappy writing – full of extended sartorial or food-related metaphors, puns and cheeky humour (the dung beetle chapter is a scatological highlight) – is a delight. (Full review forthcoming for the Times Literary Supplement.)

A late-twenties science communicator for Beaver Trust, Pavelle is enthusiastic and self-deprecating. Her nature quest takes in insects like the marsh fritillary and bilberry bumblebee and marine species such as seagrass and the Atlantic salmon. Travelling between lockdowns in 2020–1, she takes low-carbon transport wherever possible and bolsters her trip accounts with context, much of it gleaned from Zoom calls and e-mail correspondence with experts from museums and universities. Refreshingly, half the interviewees are women, and her animal subjects are never obvious choices. The snappy writing – full of extended sartorial or food-related metaphors, puns and cheeky humour (the dung beetle chapter is a scatological highlight) – is a delight. (Full review forthcoming for the Times Literary Supplement.)

With thanks to Bloomsbury Wildlife for the free copy for review.

Anthony Bourdain also appeared on my summer reading list when I reviewed

Anthony Bourdain also appeared on my summer reading list when I reviewed  My favorites seem like they could be autobiographical for the author. “The Wall” is narrated by a man who immigrated to Iowa via Berlin at age 10 in the mid-1980s. At a potluck dinner, he met Professor Johannes Weill, who gave him free English lessons. Six years later, he heard of the Berlin Wall coming down and, though he’d lost touch with the professor, made a point of sending a note. The connection across age, race and country is touching. “Sinkholes” is a short, piercing one about the single Black student in a class refusing to be the one to write the N-word on the board during a lesson on Invisible Man. The teacher is trying to make a point about not giving a word power, but it’s clear that it does have significance whether uttered or not. “Swearing In, January 20, 2009” is a poignant flash story about an immigrant’s patriotic delight in Barack Obama’s inauguration, despite prejudice encountered.

My favorites seem like they could be autobiographical for the author. “The Wall” is narrated by a man who immigrated to Iowa via Berlin at age 10 in the mid-1980s. At a potluck dinner, he met Professor Johannes Weill, who gave him free English lessons. Six years later, he heard of the Berlin Wall coming down and, though he’d lost touch with the professor, made a point of sending a note. The connection across age, race and country is touching. “Sinkholes” is a short, piercing one about the single Black student in a class refusing to be the one to write the N-word on the board during a lesson on Invisible Man. The teacher is trying to make a point about not giving a word power, but it’s clear that it does have significance whether uttered or not. “Swearing In, January 20, 2009” is a poignant flash story about an immigrant’s patriotic delight in Barack Obama’s inauguration, despite prejudice encountered.

Berger (1926–2017), an art critic and Booker Prize-winning novelist, spent six weeks shadowing the doctor, to whom he gives the pseudonym John Sassall, with Swiss documentary photographer Jean Mohr, his frequent collaborator. Sassall’s dedication was legendary: he attended every birth in this community, and nearly every death. Sassall’s middle-class origins set him apart from his patients. There’s something condescending about how Berger depicts the locals as simple peasants. Mohr’s photos include soft-focus close-ups on faces exhibiting a sequence of emotions, a technique that feels outdated in the age of video. Along with recording the day-to-day details of medical complaints and interventions, Berger waxes philosophical on topics such as infirmity and vocation. A Fortunate Man is a curious book, part intellectual enquiry and part hagiography.

Berger (1926–2017), an art critic and Booker Prize-winning novelist, spent six weeks shadowing the doctor, to whom he gives the pseudonym John Sassall, with Swiss documentary photographer Jean Mohr, his frequent collaborator. Sassall’s dedication was legendary: he attended every birth in this community, and nearly every death. Sassall’s middle-class origins set him apart from his patients. There’s something condescending about how Berger depicts the locals as simple peasants. Mohr’s photos include soft-focus close-ups on faces exhibiting a sequence of emotions, a technique that feels outdated in the age of video. Along with recording the day-to-day details of medical complaints and interventions, Berger waxes philosophical on topics such as infirmity and vocation. A Fortunate Man is a curious book, part intellectual enquiry and part hagiography.  With its layers of local history and its braided biographical strands, A Fortunate Woman takes up many of the same heavy questions but feels more subtle and timely. It also soon delivers a jolting surprise: the doctor Berger called John Sassall was likely bipolar and, soon after the death of his beloved wife Betty, committed suicide in 1982. His story still haunts this community, where many of the older patients remember going to him for treatment. Like Berger, Morland keenly follows a range of cases. As the book progresses, we see this beautiful valley cycle through the seasons, with certain of Richard Baker’s landscape shots deliberately recreating Mohr’s scene setting. The timing of Morland’s book means that it morphs from a portrait of the quotidian for a doctor and a community to, two-thirds through, an incidental record of the challenges of medical practice during COVID-19.

With its layers of local history and its braided biographical strands, A Fortunate Woman takes up many of the same heavy questions but feels more subtle and timely. It also soon delivers a jolting surprise: the doctor Berger called John Sassall was likely bipolar and, soon after the death of his beloved wife Betty, committed suicide in 1982. His story still haunts this community, where many of the older patients remember going to him for treatment. Like Berger, Morland keenly follows a range of cases. As the book progresses, we see this beautiful valley cycle through the seasons, with certain of Richard Baker’s landscape shots deliberately recreating Mohr’s scene setting. The timing of Morland’s book means that it morphs from a portrait of the quotidian for a doctor and a community to, two-thirds through, an incidental record of the challenges of medical practice during COVID-19.

Galbraith’s is an elegiac tour through imperilled countryside and urban edgelands. Each chapter resembles an in-depth magazine article: a carefully crafted profile of a beloved bird species, with a focus on the specific threats it faces. Galbraith recognises the nuances of land use. However, shooting plays an outsized role. (Curious for his bio not to disclose that he is editor of the Shooting Times.) The title’s reference is to literal birdsong, but the book also celebrates birds’ cultural importance through their place in Britain’s folk music and poetry. He is clearly enamoured of countryside ways, but too often slips into laddishness, with no opportunity missed to mention him or another man having a “piss” outside. Readers could also be forgiven for concluding that “Ilka” (no surname, affiliation or job title), who briefs him on her research into kittiwake populations in Orkney, is the only female working in nature conservation in the entire country; with few exceptions, women only have bit parts: the farm wife making the tea, the receptionist on the phone line, and so on.

Galbraith’s is an elegiac tour through imperilled countryside and urban edgelands. Each chapter resembles an in-depth magazine article: a carefully crafted profile of a beloved bird species, with a focus on the specific threats it faces. Galbraith recognises the nuances of land use. However, shooting plays an outsized role. (Curious for his bio not to disclose that he is editor of the Shooting Times.) The title’s reference is to literal birdsong, but the book also celebrates birds’ cultural importance through their place in Britain’s folk music and poetry. He is clearly enamoured of countryside ways, but too often slips into laddishness, with no opportunity missed to mention him or another man having a “piss” outside. Readers could also be forgiven for concluding that “Ilka” (no surname, affiliation or job title), who briefs him on her research into kittiwake populations in Orkney, is the only female working in nature conservation in the entire country; with few exceptions, women only have bit parts: the farm wife making the tea, the receptionist on the phone line, and so on.  Taking Flight by Lev Parikian: Parikian’s accessible account of the animal kingdom’s development of flight exhibits a layman’s enthusiasm for an everyday wonder. He explicates the range of flying strategies and the structural adaptations that made them possible. The archaeopteryx section, chronicling the transition between dinosaurs and birds, is a highlight. Though the most science-heavy of the author’s six works, this, perhaps ironically, has fewer footnotes. His usual wit is on display: he describes the feral pigeon as “the Volkswagen Golf of birds” and penguins as “piebald blubber tubes”. This makes it a pleasure to tag along on a journey through evolutionary time, one sure to engage even history- and science-phobes.

Taking Flight by Lev Parikian: Parikian’s accessible account of the animal kingdom’s development of flight exhibits a layman’s enthusiasm for an everyday wonder. He explicates the range of flying strategies and the structural adaptations that made them possible. The archaeopteryx section, chronicling the transition between dinosaurs and birds, is a highlight. Though the most science-heavy of the author’s six works, this, perhaps ironically, has fewer footnotes. His usual wit is on display: he describes the feral pigeon as “the Volkswagen Golf of birds” and penguins as “piebald blubber tubes”. This makes it a pleasure to tag along on a journey through evolutionary time, one sure to engage even history- and science-phobes.

That Barbery is a Japanophile was clear from her whimsical The Writer’s Cats, which I

That Barbery is a Japanophile was clear from her whimsical The Writer’s Cats, which I  For some years she made a living by leading tours she could never have afforded herself. Much as she loves Kyoto and its sights, she tired of the crowds and of seeing the same temples all the time. It took a stranger observing that she seemed unhappy in her work for her too realize it was time for a change.

For some years she made a living by leading tours she could never have afforded herself. Much as she loves Kyoto and its sights, she tired of the crowds and of seeing the same temples all the time. It took a stranger observing that she seemed unhappy in her work for her too realize it was time for a change.

These college students’ bond is primarily physical, with an overlay of intellectual pretentiousness: they read to each other from the likes of Proust before they go to bed. Zambra, a Chilean poet and fiction writer, zooms in and out to spotlight each one’s other connections with friends and lovers and presage how the past will lead to separate futures. Already we see Julio thinking about how this time-limited relationship will be remembered in memory and in writing. The plot of a story Zambra references in this allusion-heavy work, “Tantalia” by Macedonio Fernández, provides the title: a couple buy a small plant to signify their love, but realize that maybe wasn’t a great idea given that plants can die.

These college students’ bond is primarily physical, with an overlay of intellectual pretentiousness: they read to each other from the likes of Proust before they go to bed. Zambra, a Chilean poet and fiction writer, zooms in and out to spotlight each one’s other connections with friends and lovers and presage how the past will lead to separate futures. Already we see Julio thinking about how this time-limited relationship will be remembered in memory and in writing. The plot of a story Zambra references in this allusion-heavy work, “Tantalia” by Macedonio Fernández, provides the title: a couple buy a small plant to signify their love, but realize that maybe wasn’t a great idea given that plants can die.