#NovNov25 Begins! & My Year in Novellas

Welcome to Novellas in November! The link-up is open (see my pinned post). At the start of the month, we’re inviting you to tell us about any novellas you’ve read since last November.

I have a designated shelf of short books that I keep adding to throughout the year. Whenever I’m at secondhand bookshops, charity shops, the Little Free Library, or the public library volunteering, I’m always eyeing up thin volumes and thinking about my piles for November.

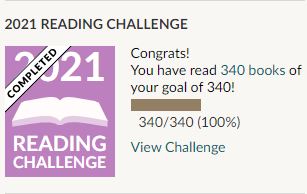

But I read novellas other times of year, too. Forty-five of them between December 2024 and now, according to my Goodreads shelves (last year the figure was 44 and the year before it was 46, so that’s my natural average). I often choose to review books of novella length for BookBrowse, Foreword and Shelf Awareness, so that helps to account for the number. I’ve read a real mixture, but predominantly literature in translation and autobiographical works.

My four favourites are ones I’ve already covered on the blog (links to my reviews): The Most by Jessica Anthony, Pale Shadows by Dominique Fortier and Three Days in June by Anne Tyler; and, in nonfiction, Mornings without Mii by Mayumi Inaba. Two works of historical fiction, one contemporary story; and a memoir of life with a cat.

What are some of your recent favourite novellas?

Three Days in June vs. Three Weeks in July

Two very good 2025 releases that I read from the library. While they could hardly be more different in tone and particulars, I couldn’t resist linking them via their titles.

Three Days in June by Anne Tyler

(From my Most Anticipated list.) A delightful little book that I loved more than I expected to, for several reasons: the effective use of a wedding weekend as a way of examining what goes wrong in marriages and what we choose to live with versus what we can’t forgive; Gail’s first-person narration, a rarity for Tyler* and a decision that adds depth to what might otherwise have been a two-dimensional depiction of a woman whose people skills leave something to be desired; and the unexpected presence of a cat who brings warmth and caprice back into her home. (I read this soon after losing my old cat, and it was comforting to be reminded that cats and their funny ways are the same the world over.)

From Tyler’s oeuvre, this reminded me most of The Amateur Marriage and has a surprise Larry’s Party-esque ending. The discussion of the outmoded practice of tapping one’s watch is a neat tie-in to her recurring theme of the nature of time. And through the lunch out at a chic crab restaurant, she succeeds at making the Baltimore setting essential rather than incidental, more so than in much of her other work.

Gail is in the sandwich generation with a daughter just married and an old mother who’s just about independent. I appreciated that she’s 61 and contemplating retirement, but still feels as if she hasn’t a clue: “What was I supposed to do with the rest of my life? I’m too young for this, I thought. Not too old, as you might expect, but too young, too inept, too uninformed. How come there weren’t any grownups around? Why did everyone just assume I knew what I was doing?”

My only misgiving is that Tyler doesn’t quite get it right about the younger generation: women who are in their early thirties in 2023 (so born about 1990) wouldn’t be called Debbie and Bitsy. To some degree, Tyler’s still stuck back in the 1970s, but her observations about married couples and family dynamics are as shrewd as ever. Especially because of the novella length, I can recommend this to readers wanting to try Tyler for the first time. ![]()

*I’ve noted it in Earthly Possessions. Anywhere else?

Three Weeks in July: 7/7, The Aftermath, and the Deadly Manhunt by Adam Wishart and James Nally

July 7th is my wedding anniversary but before that, and ever since, it’s been known as the date of the UK’s worst terrorist attack, a sort of lesser 9/11 – and while reading this I felt the same way that I’ve felt reading books about 9/11: a sort of awed horror. Suicide bombers who were born in the UK but radicalized on trips to Islamic training camps in Pakistan set off explosions on three Underground trains and one London bus. I didn’t think my memories of 7/7 were strong, yet some names were incredibly familiar to me (chiefly Mohammad Sidique Khan, the leader of the attacks; Jean Charles de Menezes, the innocent Brazilian electrician shot dead on a Tube train when confused with a suspect in the 21/7 copycat plot – police were operating under a new shoot-to-kill policy and this was the tragic result).

Fifty-two people were killed that day, ranging in age from 20 to 60; 20 were not UK citizens, hailing from everywhere from Grenada to Mauritius. But a total of 770 people were injured. I found the authors’ recreation of events very gripping, though do be warned that there is a lot of gruesome medical and forensic detail about fatalities and injuries. They humanize the scale of events and make things personal by focusing on four individuals who were injured, even losing multiple limbs in some cases, but survived and now work in motivational speaking, disability services or survivor advocacy.

Fifty-two people were killed that day, ranging in age from 20 to 60; 20 were not UK citizens, hailing from everywhere from Grenada to Mauritius. But a total of 770 people were injured. I found the authors’ recreation of events very gripping, though do be warned that there is a lot of gruesome medical and forensic detail about fatalities and injuries. They humanize the scale of events and make things personal by focusing on four individuals who were injured, even losing multiple limbs in some cases, but survived and now work in motivational speaking, disability services or survivor advocacy.

What really got to me was thinking about all the hundreds of people who, 20 years on, still live with permanent pain, disability or grief because of the randomness of them or their loved ones getting caught up in a few misguided zealots’ plot. One detail that particularly struck me: with the Tube tunnels closed off at both ends while searchers recovered bodies, the temperature rose to 50 degrees C (122 degrees F), only exacerbating the stench. The book mostly avoids cliches and overwriting, though I did find myself skimming in places. It is based on the research done for a BBC documentary series and synthesizes a lot of material in an engaging way that does justice to the victims. ![]()

Have you read one or both of these?

Could you see yourself picking one of them up?

20 Books of Summer, 17–18: Suzanne Berne and Melissa Febos

Nearly there! I’ll have two more books to review for this challenge as part of roundups tomorrow and Saturday. Today I have a lesser-known novel by a Women’s Prize winner and a set of personal essays about body image and growing up female.

A Perfect Arrangement by Suzanne Berne (2001)

Berne won the Orange (Women’s) Prize for A Crime in the Neighbourhood in 1999. This is another slice of mild suburban suspense. The Boston-area Cook-Goldman household faces increasingly disruptive problems. Architect dad Howard is vilified for a new housing estate he’s planning, plus an affair that he had with a colleague a few years ago comes back to haunt him. Hotshot lawyer Mirella can’t get the work–life balance right, especially when she finds out she’s unexpectedly pregnant with twins at age 41. They hire a new nanny to wrangle their two under-fives, headstrong Pearl and developmentally delayed Jacob. If Randi Gill seems too good to be true, that’s because she’s a pathological liar. But hey, she’s great with kids.

Berne won the Orange (Women’s) Prize for A Crime in the Neighbourhood in 1999. This is another slice of mild suburban suspense. The Boston-area Cook-Goldman household faces increasingly disruptive problems. Architect dad Howard is vilified for a new housing estate he’s planning, plus an affair that he had with a colleague a few years ago comes back to haunt him. Hotshot lawyer Mirella can’t get the work–life balance right, especially when she finds out she’s unexpectedly pregnant with twins at age 41. They hire a new nanny to wrangle their two under-fives, headstrong Pearl and developmentally delayed Jacob. If Randi Gill seems too good to be true, that’s because she’s a pathological liar. But hey, she’s great with kids.

It’s clear some Bad Stuff is going to happen to this family; the only questions are how bad and precisely what. Now, this is pretty much exactly what I want from my “summer reading”: super-readable plot- and character-driven fiction whose stakes are low (e.g., midlife malaise instead of war or genocide or whatever) and that veers more popular than literary and so can be devoured in large chunks. I really should have built more of that into my 20 Books plan! I read this much faster than I normally get through a book, but that meant the foreshadowing felt too prominent and I noticed some repetition, e.g., four or five references to purple loosestrife, which is a bit much even for those of us who like our wildflowers. It seemed a bit odd that the action was set back in the Clinton presidency; the references to the Lewinsky affair and Hillary’s “baking cookies” remark seemed to come out of nowhere. And seriously, why does the dog always have to suffer the consequences of humans’ stupid mistakes?!

This reminded me most of Friends and Strangers by J. Courtney Sullivan and a bit of Breathing Lessons by Anne Tyler, while one late plot turn took me right back to The Senator’s Wife by Sue Miller. While the Goodreads average rating of 2.93 seems pretty harsh, I can also see why fans of A Crime would have been disappointed. I probably won’t seek out any more of Berne’s fiction. (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project, Newbury) ![]()

Girlhood by Melissa Febos (2021)

I was deeply impressed by Febos’s Body Work (2022), a practical guide to crafting autobiographical narratives as a way of reckoning with the effects of trauma. Ironically, I engaged rather less with her own personal essays. One issue for me was that her highly sexualized experiences are a world away from mine. I don’t have her sense of always having had to perform for the male gaze, though maybe I’m fooling myself. Another was that it’s over 300 pages and only contains seven essays, so there were several pieces that felt endless. This was especially true of “The Mirror Test” (62 pp.) which is about double standards for girls as they played out in her simultaneous lack of confidence and slutty reputation, but randomly references The House of Mirth quite a lot; and “Thank You for Taking Care of Yourself” (74 pp.), which ponders why Febos has such trouble relaxing at a cuddle party and whether she killed off her ability to give physical consent through her years as a dominatrix.

“Wild America,” about her first lesbian experience and the way she came to love a perceived defect (freakishly large hands; they look perfectly normal to me in her author photo), and “Intrusions,” about her and other women’s experience with stalkers, worked a bit better. But my two favourites incorporated travel, a specific relationship, and a past versus present structure. “Thesmophoria” opens with her arriving in Rome for a mother–daughter vacation only to realize she told her mother the wrong month. Feeling guilty over the error, she remembers other instances when she valued her mother’s forgiveness, including when she would leave family celebrations to buy drugs. The allusions to Greek myth were neither here nor there for me, but the words about her mother’s unconditional love made me cry.

“Wild America,” about her first lesbian experience and the way she came to love a perceived defect (freakishly large hands; they look perfectly normal to me in her author photo), and “Intrusions,” about her and other women’s experience with stalkers, worked a bit better. But my two favourites incorporated travel, a specific relationship, and a past versus present structure. “Thesmophoria” opens with her arriving in Rome for a mother–daughter vacation only to realize she told her mother the wrong month. Feeling guilty over the error, she remembers other instances when she valued her mother’s forgiveness, including when she would leave family celebrations to buy drugs. The allusions to Greek myth were neither here nor there for me, but the words about her mother’s unconditional love made me cry.

I also really liked “Les Calanques,” which again draws on her history of heroin addiction, comparing a strung-out college trip to Paris when she scored with a sweet gay boy named Ahmed with the self-disciplined routines and care for her body she’d learned by the time she returns to France for a writing retreat. This felt like a good model for how to write about one’s past self. “I spend so much time with that younger self, her savage despair and fleeting reliefs, that I start to feel as though she is here with me.” The prologue, “Scarification,” is a numbered list of how she got her scars, something Paul Auster also gives in Winter Journal. As if to insist that we can only ever experience life through our bodies.

Although I’d hoped to connect to this more, and ultimately felt it wasn’t really meant for me (and maybe I’m a deficient feminist), I did admire the range of strategies and themes so will keep it on the shelf as a model for approaching the art of the personal essay. I think I would probably prefer a memoir from Febos, but don’t need to read more about her sex work (Whip Smart), so might look into Abandon Me. If bisexuality and questions of consent are of interest, you might also like Another Word for Love by Carvell Wallace, which I reviewed for BookBrowse. (Gift (secondhand) from my Christmas wish list last year) ![]()

Book Serendipity, March to April 2022

This is a bimonthly feature of mine. I call it Book Serendipity when two or more books that I read at the same time or in quick succession have something in common – the more bizarre, the better. Because I usually 20–30 books on the go at once, I suppose I’m more prone to such incidents. The following are in roughly chronological order.

(I always like hearing about your bookish coincidences, too! Laura had what she thought must be the ultimate Book Serendipity when she reviewed two novels with the same setup: Groundskeeping by Lee Cole and Last Resort by Andrew Lipstein.)

- The same sans serif font is on Sea State by Tabitha Lasley and Lean Fall Stand by Jon McGregor – both released by 4th Estate. I never would have noticed had they not ended up next to each other in my stack one day. (Then a font-alike showed up in my TBR pile, this time from different publishers, later on: What Strange Paradise by Omar El Akkad and When We Were Birds by Ayanna Lloyd Banwo.)

- Kraftwerk is mentioned in The Facebook of the Dead by Valerie Laws and How High We Go in the Dark by Sequoia Nagamatsu.

- The fact that bacteria sometimes form biofilms is mentioned in Hybrid Humans by Harry Parker and Slime by Susanne Wedlich.

- The idea that when someone dies, it’s like a library burning is repeated in The Reactor by Nick Blackburn and In the River of Songs by Susan Jackson.

- Espresso martinis are consumed in If Not for You by Georgina Lucas and Wahala by Nikki May.

- Prosthetic limbs turn up in Groundskeeping by Lee Cole, The Book of Form and Emptiness by Ruth Ozeki, and Hybrid Humans by Harry Parker.

- A character incurs a bad cut to the palm of the hand in After You’d Gone by Maggie O’Farrell and The Book of Form and Emptiness by Ruth Ozeki – I read the two scenes on the same day.

- Catfish is on the menu in Groundskeeping by Lee Cole and in one story of Antipodes by Holly Goddard Jones.

Reading two novels with “Paradise” in the title (and as the last word) at the same time: Paradise by Toni Morrison and To Paradise by Hanya Yanagihara.

Reading two novels with “Paradise” in the title (and as the last word) at the same time: Paradise by Toni Morrison and To Paradise by Hanya Yanagihara.

- Reading two books by a Davidson at once: Damnation Spring by Ash and Tracks by Robyn.

- There’s a character named Elwin in The Five Wounds by Kirstin Valdez Quade and one called Elvin in The Two Lives of Sara by Catherine Adel West.

- Tea is served with lemon in The Beginning of Spring by Penelope Fitzgerald and The Two Lives of Sara by Catherine Adel West.

- There’s a Florence (or Flo) in Go Tell It on the Mountain by James Baldwin, These Days by Lucy Caldwell and Pictures from an Institution by Randall Jarrell. (Not to mention a Flora in The Sentence by Louise Erdrich.)

There’s a hoarder character in Olga Dies Dreaming by Xóchitl González and The Book of Form and Emptiness by Ruth Ozeki.

There’s a hoarder character in Olga Dies Dreaming by Xóchitl González and The Book of Form and Emptiness by Ruth Ozeki.

- Reading at the same time two memoirs by New Yorker writers releasing within two weeks of each other (in the UK at least) and blurbed by Jia Tolentino: Home/Land by Rebecca Mead and Lost & Found by Kathryn Schulz.

- Three children play in a graveyard in Falling Angels by Tracy Chevalier and Build Your House Around My Body by Violet Kupersmith.

- Shalimar perfume is worn in These Days by Lucy Caldwell and The Five Wounds by Kirstin Valdez Quade.

- A relative is described as “very cold” and it’s wondered what made her that way in Very Cold People by Sarah Manguso and one of the testimonies in Regrets of the Dying by Georgina Scull.

Cherie Dimaline’s Empire of Wild is mentioned in The Sentence by Louise Erdrich, which I was reading at around the same time. (As is The Beginning of Spring by Penelope Fitzgerald, which I’d recently finished.)

Cherie Dimaline’s Empire of Wild is mentioned in The Sentence by Louise Erdrich, which I was reading at around the same time. (As is The Beginning of Spring by Penelope Fitzgerald, which I’d recently finished.)

- From one poetry collection with references to Islam (Bless the Daughter Raised by a Voice in Her Head by Warsan Shire) to another (Auguries of a Minor God by Nidhi Zak/Aria Eipe).

- Two children’s books featuring a building that is revealed to be a theatre: Moominsummer Madness by Tove Jansson and The Unadoptables by Hana Tooke.

- Reading two “braid” books at once: Braiding Sweetgrass by Robin Wall Kimmerer and French Braid by Anne Tyler.

- Protests and teargas in The Sentence by Louise Erdrich and The Book of Form and Emptiness by Ruth Ozeki.

- Jellyfish poems in Honorifics by Cynthia Miller and Love Poems in Quarantine by Sarah Ruhl.

- George Floyd’s murder is a major element in The Sentence by Louise Erdrich and Love Poems in Quarantine by Sarah Ruhl.

What’s the weirdest reading coincidence you’ve had lately?

A remote artist’s studio and severed fingers in Old Soul by Susan Barker and We Do Not Part by Han Kang.

A remote artist’s studio and severed fingers in Old Soul by Susan Barker and We Do Not Part by Han Kang.

A lesbian couple is alarmed by the one partner’s family keeping guns in Spent by Alison Bechdel and one story of Are You Happy? by Lori Ostlund.

A lesbian couple is alarmed by the one partner’s family keeping guns in Spent by Alison Bechdel and one story of Are You Happy? by Lori Ostlund. New York City tourist slogans in Apple of My Eye by Helene Hanff and How to Be Somebody Else by Miranda Pountney.

New York City tourist slogans in Apple of My Eye by Helene Hanff and How to Be Somebody Else by Miranda Pountney.

A stalker-ish writing student who submits an essay to his professor that seems inappropriately personal about her in one story of Are You Happy? by Lori Ostlund and If You Love It, Let It Kill You by Hannah Pittard.

A stalker-ish writing student who submits an essay to his professor that seems inappropriately personal about her in one story of Are You Happy? by Lori Ostlund and If You Love It, Let It Kill You by Hannah Pittard.

A writing professor knows she’s a hypocrite for telling her students what (not) to do and then (not) doing it herself in Trying by Chloé Caldwell and If You Love It, Let It Kill You by Hannah Pittard. These two books also involve a partner named B (or Bruce), metafiction, porch drinks with parents, and the observation that a random statement sounds like a book title.

A writing professor knows she’s a hypocrite for telling her students what (not) to do and then (not) doing it herself in Trying by Chloé Caldwell and If You Love It, Let It Kill You by Hannah Pittard. These two books also involve a partner named B (or Bruce), metafiction, porch drinks with parents, and the observation that a random statement sounds like a book title.

Shalimar perfume is mentioned in Scaffolding by Lauren Elkin and Chopping Onions on My Heart by Samantha Ellis.

Shalimar perfume is mentioned in Scaffolding by Lauren Elkin and Chopping Onions on My Heart by Samantha Ellis.

Live Fast by Brigitte Giraud (trans. from the French by Cory Stockwell) [Feb. 11, Ecco]: I found out about this autofiction novella via an early

Live Fast by Brigitte Giraud (trans. from the French by Cory Stockwell) [Feb. 11, Ecco]: I found out about this autofiction novella via an early  The Unworthy by Agustina Bazterrica (trans. from the Spanish by Sarah Moses) [13 Feb., Pushkin; March 4, Scribner]: I wasn’t enamoured of the Argentinian author’s

The Unworthy by Agustina Bazterrica (trans. from the Spanish by Sarah Moses) [13 Feb., Pushkin; March 4, Scribner]: I wasn’t enamoured of the Argentinian author’s  Victorian Psycho by Virginia Feito [13 Feb., Fourth Estate; Feb. 4, Liveright]: Feito’s debut,

Victorian Psycho by Virginia Feito [13 Feb., Fourth Estate; Feb. 4, Liveright]: Feito’s debut,

The Swell by Kat Gordon [27 Feb., Manilla Press (Bonnier Books UK)]: I got vague The Mercies (Kiran Millwood Hargrave) vibes from the blurb. “Iceland, 1910. In the middle of a severe storm two sisters, Freyja and Gudrun, rescue a mysterious, charismatic man from a shipwreck near their remote farm. Sixty-five years later, a young woman, Sigga, is spending time with her grandmother when they learn a body has been discovered on a mountainside near Reykjavik, perfectly preserved in ice.” (NetGalley download)

The Swell by Kat Gordon [27 Feb., Manilla Press (Bonnier Books UK)]: I got vague The Mercies (Kiran Millwood Hargrave) vibes from the blurb. “Iceland, 1910. In the middle of a severe storm two sisters, Freyja and Gudrun, rescue a mysterious, charismatic man from a shipwreck near their remote farm. Sixty-five years later, a young woman, Sigga, is spending time with her grandmother when they learn a body has been discovered on a mountainside near Reykjavik, perfectly preserved in ice.” (NetGalley download) Dream Count by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie [4 March, Fourth Estate/Knopf]: This is THE book I’m most looking forward to; I’ve read everything Adichie has published and Americanah was a 5-star read for me. So I did something I’ve never done before and pre-ordered the signed independent bookshop edition from my local indie, Hungerford Bookshop. “Chiamaka is a Nigerian travel writer living in America. Alone in the midst of the pandemic, she recalls her past lovers and grapples with her choices and regrets.” The focus is on four Nigerian American women “and their loves, longings, and desires.” (New purchase)

Dream Count by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie [4 March, Fourth Estate/Knopf]: This is THE book I’m most looking forward to; I’ve read everything Adichie has published and Americanah was a 5-star read for me. So I did something I’ve never done before and pre-ordered the signed independent bookshop edition from my local indie, Hungerford Bookshop. “Chiamaka is a Nigerian travel writer living in America. Alone in the midst of the pandemic, she recalls her past lovers and grapples with her choices and regrets.” The focus is on four Nigerian American women “and their loves, longings, and desires.” (New purchase) Kate & Frida by Kim Fay [March 11, G.P. Putnam’s Sons]: “Frida Rodriguez arrives in Paris in 1991 … But then she writes to a bookshop in Seattle … A friendship begins that will redefine the person she wants to become. Seattle bookseller Kate Fair is transformed by Frida’s free spirit … [A] love letter to bookshops and booksellers, to the passion we bring to life in our twenties”. Sounds like a cross between The Paris Novel and 84 Charing Cross Road – could be fab; could be twee. We shall see! (Edelweiss download)

Kate & Frida by Kim Fay [March 11, G.P. Putnam’s Sons]: “Frida Rodriguez arrives in Paris in 1991 … But then she writes to a bookshop in Seattle … A friendship begins that will redefine the person she wants to become. Seattle bookseller Kate Fair is transformed by Frida’s free spirit … [A] love letter to bookshops and booksellers, to the passion we bring to life in our twenties”. Sounds like a cross between The Paris Novel and 84 Charing Cross Road – could be fab; could be twee. We shall see! (Edelweiss download) The Antidote by Karen Russell [13 March, Chatto & Windus (Penguin) / March 11, Knopf]: I love Russell’s

The Antidote by Karen Russell [13 March, Chatto & Windus (Penguin) / March 11, Knopf]: I love Russell’s  Elegy, Southwest by Madeleine Watts [13 March, ONE (Pushkin) / Feb. 18, Simon & Schuster]: Watts’s debut,

Elegy, Southwest by Madeleine Watts [13 March, ONE (Pushkin) / Feb. 18, Simon & Schuster]: Watts’s debut,  O Sinners! by Nicole Cuffy [March 18, One World (Random House)]: Cuffy’s

O Sinners! by Nicole Cuffy [March 18, One World (Random House)]: Cuffy’s  The Accidentals: Stories by Guadalupe Nettel (trans. from the Spanish by Rosalind Harvey) [10 April, Fitzcarraldo Editions / April 29, Bloomsbury]: I really enjoyed Nettel’s International Booker-shortlisted novel

The Accidentals: Stories by Guadalupe Nettel (trans. from the Spanish by Rosalind Harvey) [10 April, Fitzcarraldo Editions / April 29, Bloomsbury]: I really enjoyed Nettel’s International Booker-shortlisted novel  Ordinary Saints by Niamh Ni Mhaoileoin [24 April, Manilla Press (Bonnier Books UK)]: “Brought up in a devout household in Ireland, Jay is now living in London with her girlfriend, determined to live day to day and not think too much about either the future or the past. But when she learns that her beloved older brother, who died in a terrible accident, may be made into a Catholic saint, she realises she must at last confront her family, her childhood and herself.” Winner of the inaugural PFD Queer Fiction Prize and shortlisted for the Women’s Prize Discoveries Award.

Ordinary Saints by Niamh Ni Mhaoileoin [24 April, Manilla Press (Bonnier Books UK)]: “Brought up in a devout household in Ireland, Jay is now living in London with her girlfriend, determined to live day to day and not think too much about either the future or the past. But when she learns that her beloved older brother, who died in a terrible accident, may be made into a Catholic saint, she realises she must at last confront her family, her childhood and herself.” Winner of the inaugural PFD Queer Fiction Prize and shortlisted for the Women’s Prize Discoveries Award. Heartwood by Amity Gaige [1 May, Fleet / April 1, Simon & Schuster]: I loved Gaige’s

Heartwood by Amity Gaige [1 May, Fleet / April 1, Simon & Schuster]: I loved Gaige’s  Ripeness by Sarah Moss [22 May, Picador / Sept. 9, Farrar, Straus and Giroux]: Though I was disappointed by her last two novels, I’ll read anything Moss publishes and hope for a return to form. “It is the [19]60s and … Edith finds herself travelling to rural Italy … to see her sister, ballet dancer Lydia, through the final weeks of her pregnancy, help at the birth and then make a phone call which will seal this baby’s fate, and his mother’s.” Promises to be “about migration and new beginnings, and about what it is to have somewhere to belong.”

Ripeness by Sarah Moss [22 May, Picador / Sept. 9, Farrar, Straus and Giroux]: Though I was disappointed by her last two novels, I’ll read anything Moss publishes and hope for a return to form. “It is the [19]60s and … Edith finds herself travelling to rural Italy … to see her sister, ballet dancer Lydia, through the final weeks of her pregnancy, help at the birth and then make a phone call which will seal this baby’s fate, and his mother’s.” Promises to be “about migration and new beginnings, and about what it is to have somewhere to belong.” The Forgotten Sense: The New Science of Smell by Jonas Olofsson [Out now! 7 Jan., William Collins / Mariner]: Part of a planned deep dive into the senses. “Smell is … one of our most sensitive and refined senses; few other mammals surpass our ability to perceive scents in the animal kingdom. Yet, as the millions of people who lost their sense of smell during the COVID-19 pandemic can attest, we too often overlook its role in our overall health. … For readers of Bill Bryson and Steven Pinker”. (On order from library)

The Forgotten Sense: The New Science of Smell by Jonas Olofsson [Out now! 7 Jan., William Collins / Mariner]: Part of a planned deep dive into the senses. “Smell is … one of our most sensitive and refined senses; few other mammals surpass our ability to perceive scents in the animal kingdom. Yet, as the millions of people who lost their sense of smell during the COVID-19 pandemic can attest, we too often overlook its role in our overall health. … For readers of Bill Bryson and Steven Pinker”. (On order from library) Bread and Milk by Karolina Ramqvist (trans. from the Swedish by Saskia Vogel) [13 Feb., Bonnier Books / Feb. 11, Coach House Books]: I think I first found about this via the early

Bread and Milk by Karolina Ramqvist (trans. from the Swedish by Saskia Vogel) [13 Feb., Bonnier Books / Feb. 11, Coach House Books]: I think I first found about this via the early  My Mother in Havana: A Memoir of Magic & Miracle by Rebe Huntman [Feb. 18, Monkfish]: I found out about this from

My Mother in Havana: A Memoir of Magic & Miracle by Rebe Huntman [Feb. 18, Monkfish]: I found out about this from  Mother Animal by Helen Jukes [27 Feb., Elliott & Thompson]: This may be the 2025 release I’ve known about for the longest. I remember expressing interest the first time the author tweeted about it; it’s bound to be a good follow-up to Lucy Jones’s

Mother Animal by Helen Jukes [27 Feb., Elliott & Thompson]: This may be the 2025 release I’ve known about for the longest. I remember expressing interest the first time the author tweeted about it; it’s bound to be a good follow-up to Lucy Jones’s  Alive: An Alternative Anatomy by Gabriel Weston [6 March, Vintage (Penguin) / March 4, David R. Godine]: I’ve read Weston’s

Alive: An Alternative Anatomy by Gabriel Weston [6 March, Vintage (Penguin) / March 4, David R. Godine]: I’ve read Weston’s  Breasts: A Relatively Brief Relationship by Jean Hannah Edelstein [3 April, Phoenix (W&N)]: I loved Edelstein’s 2018 memoir

Breasts: A Relatively Brief Relationship by Jean Hannah Edelstein [3 April, Phoenix (W&N)]: I loved Edelstein’s 2018 memoir  Poets Square: A Memoir in Thirty Cats by Courtney Gustafson [8 May, Fig Tree (Penguin) / April 29, Crown]: Gustafson became an Instagram and TikTok hit with her posts about looking after a feral cat colony in Tucson, Arizona. The money she raised via social media allowed her to buy her home and continue caring for animals. “[Gustafson] had no idea about the grief and hardship of animal rescue, the staggering size of the problem in neighborhoods across the country. And she couldn’t have imagined how that struggle … would help pierce a personal darkness she’d wrestled for with much of her life.” (Proof copy from publisher)

Poets Square: A Memoir in Thirty Cats by Courtney Gustafson [8 May, Fig Tree (Penguin) / April 29, Crown]: Gustafson became an Instagram and TikTok hit with her posts about looking after a feral cat colony in Tucson, Arizona. The money she raised via social media allowed her to buy her home and continue caring for animals. “[Gustafson] had no idea about the grief and hardship of animal rescue, the staggering size of the problem in neighborhoods across the country. And she couldn’t have imagined how that struggle … would help pierce a personal darkness she’d wrestled for with much of her life.” (Proof copy from publisher) Lifelines: Searching for Home in the Mountains of Greece by Julian Hoffman [15 May, Elliott & Thompson]: Hoffman’s

Lifelines: Searching for Home in the Mountains of Greece by Julian Hoffman [15 May, Elliott & Thompson]: Hoffman’s

This posthumous novella was written in the 1940s but never published in Brennan’s lifetime. From Dublin, she was a longtime New Yorker staff member and wrote acclaimed short stories. After her mother’s death, Anastasia King travels from Paris, where the two set up residence after leaving her father, to Ireland to stay in the family home with her grandmother. Anastasia considers it a return, a homecoming, but her spiteful grandmother makes it clear that she is an unwelcome interloper. Mrs King can’t forgive the wrong done to her son, and so won’t countenance Anastasia’s plan to repatriate her mother’s remains. Rejection and despair eat away at Anastasia’s mental health (“She saw the miserable gate of her defeat already open ahead. There only remained for her to come up to it and pass through it and be done with it”) but she pulls herself together for an act of defiance. Most affecting for me was a scene in which we learn that Anastasia is so absorbed in her own drama that she does not fulfill the simple last wish of a dying friend. This brought to mind James Joyce’s The Dead. (Secondhand purchase – The Bookshop, Wigtown) [81 pages]

This posthumous novella was written in the 1940s but never published in Brennan’s lifetime. From Dublin, she was a longtime New Yorker staff member and wrote acclaimed short stories. After her mother’s death, Anastasia King travels from Paris, where the two set up residence after leaving her father, to Ireland to stay in the family home with her grandmother. Anastasia considers it a return, a homecoming, but her spiteful grandmother makes it clear that she is an unwelcome interloper. Mrs King can’t forgive the wrong done to her son, and so won’t countenance Anastasia’s plan to repatriate her mother’s remains. Rejection and despair eat away at Anastasia’s mental health (“She saw the miserable gate of her defeat already open ahead. There only remained for her to come up to it and pass through it and be done with it”) but she pulls herself together for an act of defiance. Most affecting for me was a scene in which we learn that Anastasia is so absorbed in her own drama that she does not fulfill the simple last wish of a dying friend. This brought to mind James Joyce’s The Dead. (Secondhand purchase – The Bookshop, Wigtown) [81 pages]

If you’ve heard of this, it’ll be for the fact that the main character – Lou, a librarian sent to archive the holdings of an octagonal house on an island one summer – has sex with a bear. That makes it sound much more repulsive and/or titillating than it actually is. The further I read the more I started to think of it as an allegory for women’s awakening; perhaps the strategy inspired Melissa Broder’s

If you’ve heard of this, it’ll be for the fact that the main character – Lou, a librarian sent to archive the holdings of an octagonal house on an island one summer – has sex with a bear. That makes it sound much more repulsive and/or titillating than it actually is. The further I read the more I started to think of it as an allegory for women’s awakening; perhaps the strategy inspired Melissa Broder’s  Several of us reviewed this for #NovNov though unsure it counts: in the UK the title story (originally for the New Yorker) was published in a standalone volume by Faber, while the U.S. release includes two additional earlier stories; I read the latter. The title story has Cathal spending what should have been his wedding weekend moping about Sabine calling off their engagement at the last minute. It’s no mystery why she did: his misogyny, though not overt, runs deep, most evident in the terms in which he thinks about women. And where did he learn it? From his father. (“The Long and Painful Death” is from Keegan’s second collection, Walk the Blue Fields, and concerns a woman on a writing residency at an author’s historic house in Ireland. She makes a stand for her own work by refusing to cede place to an entitled male scholar. The final story is “Antarctica,” the lead story in that 1999 volume and a really terrific one I’d already experienced before. It’s as dark and surprising as an early Ian McEwan novel.) Keegan proves, as ever, to be a master at portraying emotions and relationships, but the one story is admittedly slight on its own, and its point obvious. (Read via Edelweiss) [64 pages]

Several of us reviewed this for #NovNov though unsure it counts: in the UK the title story (originally for the New Yorker) was published in a standalone volume by Faber, while the U.S. release includes two additional earlier stories; I read the latter. The title story has Cathal spending what should have been his wedding weekend moping about Sabine calling off their engagement at the last minute. It’s no mystery why she did: his misogyny, though not overt, runs deep, most evident in the terms in which he thinks about women. And where did he learn it? From his father. (“The Long and Painful Death” is from Keegan’s second collection, Walk the Blue Fields, and concerns a woman on a writing residency at an author’s historic house in Ireland. She makes a stand for her own work by refusing to cede place to an entitled male scholar. The final story is “Antarctica,” the lead story in that 1999 volume and a really terrific one I’d already experienced before. It’s as dark and surprising as an early Ian McEwan novel.) Keegan proves, as ever, to be a master at portraying emotions and relationships, but the one story is admittedly slight on its own, and its point obvious. (Read via Edelweiss) [64 pages]  “She is Europe’s eerie child, and she is part of the storm.” J.K. is a young woman who totes her typewriter around different European locations, sleeps with various boyfriends, hears strangers’ stories, and so on. Many of the people she meets are only designated by an initial. By contrast, the most fully realized character is her mother, Lillian Strauss. The chapters feel unconnected and the encounters within them random, building to nothing. Though a bit like

“She is Europe’s eerie child, and she is part of the storm.” J.K. is a young woman who totes her typewriter around different European locations, sleeps with various boyfriends, hears strangers’ stories, and so on. Many of the people she meets are only designated by an initial. By contrast, the most fully realized character is her mother, Lillian Strauss. The chapters feel unconnected and the encounters within them random, building to nothing. Though a bit like

Meier is a cemetery tour guide in Brooklyn, where she lives. She surveys American burial customs in particular, noting the lack of respect for Black and Native American burial grounds, the Civil War-era history of embalming, the increasing popularity of cremation, and the rise of garden cemeteries such as Mount Auburn in Cambridge, Massachusetts, which can serve as wildlife havens. The mass casualties and fear of infection associated with Covid-19 brought back memories of the AIDS epidemic, especially for those in New York City. Meier travels to a wide range of resting places, from potter’s fields for unclaimed bodies to the most manicured cemeteries. She also talks about newer options such as green burial, body composting, and the many memorial objects ashes can be turned into. I’m a dedicated reader of books about death and so found this fascinating, with the perfect respectful and just-shy-of-melancholy tone. It’s political and philosophical in equal measures. (Read via NetGalley) [168 pages]

Meier is a cemetery tour guide in Brooklyn, where she lives. She surveys American burial customs in particular, noting the lack of respect for Black and Native American burial grounds, the Civil War-era history of embalming, the increasing popularity of cremation, and the rise of garden cemeteries such as Mount Auburn in Cambridge, Massachusetts, which can serve as wildlife havens. The mass casualties and fear of infection associated with Covid-19 brought back memories of the AIDS epidemic, especially for those in New York City. Meier travels to a wide range of resting places, from potter’s fields for unclaimed bodies to the most manicured cemeteries. She also talks about newer options such as green burial, body composting, and the many memorial objects ashes can be turned into. I’m a dedicated reader of books about death and so found this fascinating, with the perfect respectful and just-shy-of-melancholy tone. It’s political and philosophical in equal measures. (Read via NetGalley) [168 pages]

Laboratory pregnancy tests have been available since the 1930s and home pregnancy tests – the focus here – since the 1970s. All of them work by testing urine for the hormone hCG (human chorionic gonadotropin). What is truly wild is that pregnancy used to be verifiable only with laboratory animals – female mice and rabbits had to be sacrificed to see if their ovaries had swelled after the injection of a woman’s urine; later, female Xenopus toads were found to lay eggs in response, so didn’t need to be killed. Home pregnancy kits were controversial and available in Canada before the USA because it was thought that they could be unreliable or that they would encourage early abortions. Weingarten brings together the history, laypeople-friendly science, and cultural representations (taking a pregnancy test is excellent TV shorthand) in a readable narrative and makes a clear feminist statement: “the home pregnancy test gave back to women what should have always been theirs: first-hand knowledge about how their bodies worked” and thus “had the potential to upend a paternalistic culture.” (Read via NetGalley) [160 pages]

Laboratory pregnancy tests have been available since the 1930s and home pregnancy tests – the focus here – since the 1970s. All of them work by testing urine for the hormone hCG (human chorionic gonadotropin). What is truly wild is that pregnancy used to be verifiable only with laboratory animals – female mice and rabbits had to be sacrificed to see if their ovaries had swelled after the injection of a woman’s urine; later, female Xenopus toads were found to lay eggs in response, so didn’t need to be killed. Home pregnancy kits were controversial and available in Canada before the USA because it was thought that they could be unreliable or that they would encourage early abortions. Weingarten brings together the history, laypeople-friendly science, and cultural representations (taking a pregnancy test is excellent TV shorthand) in a readable narrative and makes a clear feminist statement: “the home pregnancy test gave back to women what should have always been theirs: first-hand knowledge about how their bodies worked” and thus “had the potential to upend a paternalistic culture.” (Read via NetGalley) [160 pages]  The dc Talk album Jesus Freak (1995) is the first CD I ever owned. My best friend and I listened to it (along with Bloom by Audio Adrenaline and Take Me to Your Leader by Newsboys) so many times that we knew every word and note by heart. So it’s hard for me to be objective rather than nostalgic; I was intrigued to see what two secular academics would have to say. Crucially, they were teenage dc Talk fans, now ex-Evangelicals and homosexual partners. As English professors, their approach is to spot musical influences (Nirvana on the title track; R&B and gospel elsewhere), critically analyse lyrics (with “Colored People” proving problematic for its “neoliberal multiculturalism and its potential for post-racial utopianism”), and put a queer spin on things. For those who don’t know, dc Talk were essentially a boy band with three singers, one Black and two white – one of these a rapper. Stockton and Gilson chronicle the confusion of living with a same-sex attraction they couldn’t express as teens, and cheekily suggest there may have been something going on between dc Talk members Toby McKeehan and Michael Tait, who were roommates at Liberty University and apparently dismantled their bunk beds so they could sleep side by side. Hmmm! I was interested enough in the subject matter to overlook the humanities jargon. (Birthday gift from my wish list last year) [132 pages]

The dc Talk album Jesus Freak (1995) is the first CD I ever owned. My best friend and I listened to it (along with Bloom by Audio Adrenaline and Take Me to Your Leader by Newsboys) so many times that we knew every word and note by heart. So it’s hard for me to be objective rather than nostalgic; I was intrigued to see what two secular academics would have to say. Crucially, they were teenage dc Talk fans, now ex-Evangelicals and homosexual partners. As English professors, their approach is to spot musical influences (Nirvana on the title track; R&B and gospel elsewhere), critically analyse lyrics (with “Colored People” proving problematic for its “neoliberal multiculturalism and its potential for post-racial utopianism”), and put a queer spin on things. For those who don’t know, dc Talk were essentially a boy band with three singers, one Black and two white – one of these a rapper. Stockton and Gilson chronicle the confusion of living with a same-sex attraction they couldn’t express as teens, and cheekily suggest there may have been something going on between dc Talk members Toby McKeehan and Michael Tait, who were roommates at Liberty University and apparently dismantled their bunk beds so they could sleep side by side. Hmmm! I was interested enough in the subject matter to overlook the humanities jargon. (Birthday gift from my wish list last year) [132 pages]

Grumbach died last year at age 104. This was my third of her books; I read two previous memoirs,

Grumbach died last year at age 104. This was my third of her books; I read two previous memoirs,  It feels like I made an error by reading Levy’s “Living Autobiography,” out of order. I picked up the middle volume of the trilogy, The Cost of Living, for #NovNov in 2021 and it ended up being my favourite nonfiction read of that year. I then read part of the third book, Real Estate, last year but set it aside. And now I’ve read the first because it was the shortest. It’s loosely structured around George Orwell’s four reasons for writing: political purpose, historical impulse, sheer egoism and aesthetic enthusiasm. The frame story has her flying to Majorca at a time when she was struggling with her mental health. She vaguely follows in the footsteps of George Sand and then pauses to tell a Chinese shopkeeper the story of her upbringing in apartheid-era South Africa and the family’s move to London. Although I generally admire recreations of childhood and there are some strong pen portraits of minor characters, overall there was little that captivated me here and I was too aware of the writerly shaping. (Secondhand purchase – 2nd & Charles, Hagerstown) [111 pages]

It feels like I made an error by reading Levy’s “Living Autobiography,” out of order. I picked up the middle volume of the trilogy, The Cost of Living, for #NovNov in 2021 and it ended up being my favourite nonfiction read of that year. I then read part of the third book, Real Estate, last year but set it aside. And now I’ve read the first because it was the shortest. It’s loosely structured around George Orwell’s four reasons for writing: political purpose, historical impulse, sheer egoism and aesthetic enthusiasm. The frame story has her flying to Majorca at a time when she was struggling with her mental health. She vaguely follows in the footsteps of George Sand and then pauses to tell a Chinese shopkeeper the story of her upbringing in apartheid-era South Africa and the family’s move to London. Although I generally admire recreations of childhood and there are some strong pen portraits of minor characters, overall there was little that captivated me here and I was too aware of the writerly shaping. (Secondhand purchase – 2nd & Charles, Hagerstown) [111 pages]  I reviewed a couple of JLS’s species-specific monographs for #NovNov in 2018:

I reviewed a couple of JLS’s species-specific monographs for #NovNov in 2018:  I’ve read so many cancer stories that it takes a lot to make one stand out. This feels like a random collection of documents rather than a coherent memoir. One of the three essays was originally a speech, and two were previously printed in another of her books. Lorde was diagnosed with breast cancer in 1978 and had a mastectomy. A Black lesbian feminist, she resisted wearing prostheses and spoke up about the potential environmental causes of breast cancer that need to be addressed in research (“I may be a casualty in the cosmic war against radiation, animal fat, air pollution, McDonald’s hamburgers and Red Dye No. 2”). Her actual journal entries make up little of the text, which is for the best because fear and pain can bring out the cliches in us – but occasionally a great quote like “if bitterness were a whetstone, I could be sharp as grief.” Another favourite line: “Pain does not mellow you, nor does it ennoble, in my experience.” I’m keen to read her memoir Zami. (University library) [77 pages]

I’ve read so many cancer stories that it takes a lot to make one stand out. This feels like a random collection of documents rather than a coherent memoir. One of the three essays was originally a speech, and two were previously printed in another of her books. Lorde was diagnosed with breast cancer in 1978 and had a mastectomy. A Black lesbian feminist, she resisted wearing prostheses and spoke up about the potential environmental causes of breast cancer that need to be addressed in research (“I may be a casualty in the cosmic war against radiation, animal fat, air pollution, McDonald’s hamburgers and Red Dye No. 2”). Her actual journal entries make up little of the text, which is for the best because fear and pain can bring out the cliches in us – but occasionally a great quote like “if bitterness were a whetstone, I could be sharp as grief.” Another favourite line: “Pain does not mellow you, nor does it ennoble, in my experience.” I’m keen to read her memoir Zami. (University library) [77 pages]  I’d not read Matar before I spotted this art book-cum-memoir and thought, why not. A Libyan American novelist who lives in London, Matar had long been fascinated by the Sienese School of painting (13th to 15th centuries), many of whose artists depicted biblical scenes or religious allegories – even though he’s not a Christian. He spent a month in Italy immersed in the art he loves; there are 15 colour reproductions here. His explications of art history are generalist enough to be accessible to all readers, but I engaged more with the glimpses into his own life. For instance, he meets a fellow Arabic speaker and they quickly form a brotherly attachment, and a Paradise scene gives him fanciful hope of being reunited with his missing father – the subject of his Folio Prize-winning memoir The Return, which I’d like to read soon. His prose is beautiful as he reflects on history, death and how memories occupy ‘rooms’ in the imagination. A little more interest in the art would have helped, though. (Little Free Library) [118 pages]

I’d not read Matar before I spotted this art book-cum-memoir and thought, why not. A Libyan American novelist who lives in London, Matar had long been fascinated by the Sienese School of painting (13th to 15th centuries), many of whose artists depicted biblical scenes or religious allegories – even though he’s not a Christian. He spent a month in Italy immersed in the art he loves; there are 15 colour reproductions here. His explications of art history are generalist enough to be accessible to all readers, but I engaged more with the glimpses into his own life. For instance, he meets a fellow Arabic speaker and they quickly form a brotherly attachment, and a Paradise scene gives him fanciful hope of being reunited with his missing father – the subject of his Folio Prize-winning memoir The Return, which I’d like to read soon. His prose is beautiful as he reflects on history, death and how memories occupy ‘rooms’ in the imagination. A little more interest in the art would have helped, though. (Little Free Library) [118 pages]

I had high hopes for this childhood memoir that originally appeared in the New Yorker and was reprinted as part of the Canongate Classics series. But I soon resorted to skimming as her recollections of her shabby upper-class upbringing in a Highlands castle are full of page after page of description and dull recounting of events, with few scenes and little dialogue. This would be of high historical value for someone wanting to understand daily life for a certain fraction of society at the time, however. When Miller’s father died, she was only 10 and they had to leave the castle. I was intrigued to learn from her bio that she lived in Newbury for a time. (Secondhand purchase – Barter Books) [98 pages]

I had high hopes for this childhood memoir that originally appeared in the New Yorker and was reprinted as part of the Canongate Classics series. But I soon resorted to skimming as her recollections of her shabby upper-class upbringing in a Highlands castle are full of page after page of description and dull recounting of events, with few scenes and little dialogue. This would be of high historical value for someone wanting to understand daily life for a certain fraction of society at the time, however. When Miller’s father died, she was only 10 and they had to leave the castle. I was intrigued to learn from her bio that she lived in Newbury for a time. (Secondhand purchase – Barter Books) [98 pages]  This collection of micro-essays under themed headings like “Living in the Present” and “Suffering” was a perfect introduction to Nouwen’s life and theology. The Dutch Catholic priest lived in an Ontario community serving the physically and mentally disabled, and died of a heart attack just two years after this was published. I marked out many reassuring or thought-provoking passages. Here’s a good pre-Christmas one:

This collection of micro-essays under themed headings like “Living in the Present” and “Suffering” was a perfect introduction to Nouwen’s life and theology. The Dutch Catholic priest lived in an Ontario community serving the physically and mentally disabled, and died of a heart attack just two years after this was published. I marked out many reassuring or thought-provoking passages. Here’s a good pre-Christmas one:

My only reread for the month. Wilde wrote this from prison. No doubt he had a miserable time there, but keeping in mind that he was a flamboyant dramatist and had an eye to this being published someday, this time around I found it more exaggerated and self-pitying than I had before. “Suffering is one very long moment. … Where there is sorrow there is holy ground,” he writes, stating that he has found “harmony with the wounded, broken, and great heart of the world.” He says he’s not going to try to defend his behaviour … but what is this but one extended apologia and humble brag, likening himself to a Greek tragic hero (“The gods had given me almost everything. But I let myself be lured into long spells of senseless and sensual ease. I amused myself with being a flâneur, a dandy, a man of fashion”) and even to Christ in his individuality as well as in his suffering at the hands of those who don’t understand him (the scene where he was pilloried consciously mimics a crucifixion tableau). As a literary document, it’s extraordinary, but I didn’t buy his sincerity. He feigns remorse but, really, wasn’t sorry about anything, merely sorry he got caught. (Free from a neighbour) [151 pages]

My only reread for the month. Wilde wrote this from prison. No doubt he had a miserable time there, but keeping in mind that he was a flamboyant dramatist and had an eye to this being published someday, this time around I found it more exaggerated and self-pitying than I had before. “Suffering is one very long moment. … Where there is sorrow there is holy ground,” he writes, stating that he has found “harmony with the wounded, broken, and great heart of the world.” He says he’s not going to try to defend his behaviour … but what is this but one extended apologia and humble brag, likening himself to a Greek tragic hero (“The gods had given me almost everything. But I let myself be lured into long spells of senseless and sensual ease. I amused myself with being a flâneur, a dandy, a man of fashion”) and even to Christ in his individuality as well as in his suffering at the hands of those who don’t understand him (the scene where he was pilloried consciously mimics a crucifixion tableau). As a literary document, it’s extraordinary, but I didn’t buy his sincerity. He feigns remorse but, really, wasn’t sorry about anything, merely sorry he got caught. (Free from a neighbour) [151 pages] From the cover, I was expecting this to be more foodie than it was. The protagonist does enjoy cooking for other people and reading cookbooks, though. Betta Nolan, 55 and recently widowed by cancer, drives from Boston to the Midwest and impulsively purchases a house in a Chicago suburb, something she and her late husband had fantasized about doing in retirement. It’s the kind of sweet little town where the only realtor is a one-woman operation and Betta as a newcomer automatically gets invited onto the local radio show. She also reconnects with her college roommates, tries dating, and mulls over her dream of opening a women’s boutique that sells silk scarves, handmade journals, essential oils and brownies.

From the cover, I was expecting this to be more foodie than it was. The protagonist does enjoy cooking for other people and reading cookbooks, though. Betta Nolan, 55 and recently widowed by cancer, drives from Boston to the Midwest and impulsively purchases a house in a Chicago suburb, something she and her late husband had fantasized about doing in retirement. It’s the kind of sweet little town where the only realtor is a one-woman operation and Betta as a newcomer automatically gets invited onto the local radio show. She also reconnects with her college roommates, tries dating, and mulls over her dream of opening a women’s boutique that sells silk scarves, handmade journals, essential oils and brownies.

One of the more bizarre books I’ve ever read. I loved both

One of the more bizarre books I’ve ever read. I loved both

The problem with her final book is that I’ve read so much about preparations for dying and the question of assisted suicide and she doesn’t bring much new to the discussion – apart from the specific viewpoint of someone deciding when and how to end their life when they don’t know what the future course of their illness looks like. Mitchell believes people should have this choice, but current UK law does not allow for assisted dying. A loophole is voluntarily stopping eating and drinking (VSED), which she deems her best option. She stopped attending assessments in 2017 and has filed forms with her GP refusing treatment – her nightmare situation is being reliant on care in hospital and she doesn’t want to become that future, dependent Wendy.

The problem with her final book is that I’ve read so much about preparations for dying and the question of assisted suicide and she doesn’t bring much new to the discussion – apart from the specific viewpoint of someone deciding when and how to end their life when they don’t know what the future course of their illness looks like. Mitchell believes people should have this choice, but current UK law does not allow for assisted dying. A loophole is voluntarily stopping eating and drinking (VSED), which she deems her best option. She stopped attending assessments in 2017 and has filed forms with her GP refusing treatment – her nightmare situation is being reliant on care in hospital and she doesn’t want to become that future, dependent Wendy.

All Down Darkness Wide by Seán Hewitt: This poetic memoir about love and loss in the shadow of mental illness blends biography, queer history and raw personal experience. The book opens, unforgettably, in a Liverpool graveyard where Hewitt has assignations with anonymous men. His secret self, suppressed during teenage years in the closet, flies out to meet other ghosts: of his college boyfriend; of men lost to AIDS during his 1990s childhood; of English poet George Manley Hopkins; and of a former partner who was suicidal. (Coming out on July 12th from Penguin/Vintage (USA) and July 14th from Jonathan Cape (UK). My full review is forthcoming for Shelf Awareness.)

All Down Darkness Wide by Seán Hewitt: This poetic memoir about love and loss in the shadow of mental illness blends biography, queer history and raw personal experience. The book opens, unforgettably, in a Liverpool graveyard where Hewitt has assignations with anonymous men. His secret self, suppressed during teenage years in the closet, flies out to meet other ghosts: of his college boyfriend; of men lost to AIDS during his 1990s childhood; of English poet George Manley Hopkins; and of a former partner who was suicidal. (Coming out on July 12th from Penguin/Vintage (USA) and July 14th from Jonathan Cape (UK). My full review is forthcoming for Shelf Awareness.)

My simple reading goals for 2021 were to read more biographies, classics, doorstoppers and travel books – genres that tend to sit on my shelves unread. I read one biography in graphic novel form (Orwell by Pierre Christin), but otherwise didn’t manage any. I only read three doorstoppers the whole year, but 29 classics – defining them is always a nebulous matter, but I’m going with books from before 1980 – a number I’m happy with.

My simple reading goals for 2021 were to read more biographies, classics, doorstoppers and travel books – genres that tend to sit on my shelves unread. I read one biography in graphic novel form (Orwell by Pierre Christin), but otherwise didn’t manage any. I only read three doorstoppers the whole year, but 29 classics – defining them is always a nebulous matter, but I’m going with books from before 1980 – a number I’m happy with. Surprisingly, I did the best with travel books, perhaps because I’ve started thinking about travel writing more broadly and not just as a white man going to the other side of the world and seeing exotic things, since I don’t often enjoy such narratives. Granted, I did read a few like that, and they were exceptional (The Glitter in the Green by Jon Dunn, The Shadow of the Sun by Ryszard Kapuściński and Kings of the Yukon by Adam Weymouth), but if I include essays, memoirs and poetry with significant place-based and migration themes, I was at 26.

Surprisingly, I did the best with travel books, perhaps because I’ve started thinking about travel writing more broadly and not just as a white man going to the other side of the world and seeing exotic things, since I don’t often enjoy such narratives. Granted, I did read a few like that, and they were exceptional (The Glitter in the Green by Jon Dunn, The Shadow of the Sun by Ryszard Kapuściński and Kings of the Yukon by Adam Weymouth), but if I include essays, memoirs and poetry with significant place-based and migration themes, I was at 26.

A 2021 book that everyone loved but me: The Lincoln Highway by Amor Towles.

A 2021 book that everyone loved but me: The Lincoln Highway by Amor Towles.