20 Books of Summer, 13–16: Tony Chan, Jen Hadfield, Kenward Anthology, Catherine Taylor

Three from my initial list (all nonfiction) and one substitute picked up at random (poetry). These are strongly place-based selections, ranging from Sheffield to Shetland and drawing on travels while also commenting on how gender and dis/ability affect daily life as well as the experience of nature.

Four Points Fourteen Lines by Tony Chan (2016)

Chan is a schoolteacher who, in 2015, left his day job to undertake a 78-day solo walk between “the four extreme cardinal points of the British mainland”: Dunnet Head (North) to Ardnamurchan Point (West) in Scotland, down to Lowestoft Ness (East) in Suffolk and across to Lizard Point, Cornwall (South). It was a solo trek of 1,400 miles. He wrote one sonnet per day, not always adhering to the same rhyme scheme but fitting his sentiments into 14 lines of standard length. He doesn’t document much practical information, but does admit he stayed in decent hotels, ate hot meals, etc. Each poem is named for the starting point and destination, but the topic might be what he sees, an experience on the road, a memory, or whatever. “Evanton to Inverness” decries a gloomy city; “Inverness to Foyers” gives thanks for his shoes and lycra undershorts. He compares Highlanders to heroic Trojans: “Something sincere in their browned, moss-green tweeds, / In their greeting voice of gentle tenor. / From ancient Hector or from ancient clans, / Here live men most earnest in words and deeds.” None of the poems are laudable in their own right, but it’s a pleasant enough project. Too often, though, Chan resorts to outmoded vocabulary to fit the form or try to prove a poetic pedigree (“Suddenly comes an Old Testament of deluge and / Tempest, deluding the sense wholly”; “I know these streets, whence they come and whither / They run”; “I learnt well some verses of Tennyson / Years ago when noble dreams were begat”) when he might have been better off varying the form and/or using free verse. (Signed copy from Little Free Library)

Chan is a schoolteacher who, in 2015, left his day job to undertake a 78-day solo walk between “the four extreme cardinal points of the British mainland”: Dunnet Head (North) to Ardnamurchan Point (West) in Scotland, down to Lowestoft Ness (East) in Suffolk and across to Lizard Point, Cornwall (South). It was a solo trek of 1,400 miles. He wrote one sonnet per day, not always adhering to the same rhyme scheme but fitting his sentiments into 14 lines of standard length. He doesn’t document much practical information, but does admit he stayed in decent hotels, ate hot meals, etc. Each poem is named for the starting point and destination, but the topic might be what he sees, an experience on the road, a memory, or whatever. “Evanton to Inverness” decries a gloomy city; “Inverness to Foyers” gives thanks for his shoes and lycra undershorts. He compares Highlanders to heroic Trojans: “Something sincere in their browned, moss-green tweeds, / In their greeting voice of gentle tenor. / From ancient Hector or from ancient clans, / Here live men most earnest in words and deeds.” None of the poems are laudable in their own right, but it’s a pleasant enough project. Too often, though, Chan resorts to outmoded vocabulary to fit the form or try to prove a poetic pedigree (“Suddenly comes an Old Testament of deluge and / Tempest, deluding the sense wholly”; “I know these streets, whence they come and whither / They run”; “I learnt well some verses of Tennyson / Years ago when noble dreams were begat”) when he might have been better off varying the form and/or using free verse. (Signed copy from Little Free Library) ![]()

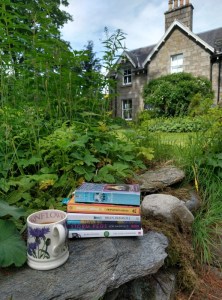

Storm Pegs: A Life Made in Shetland by Jen Hadfield (2024)

This is not so much a straightforward memoir as a set of atmospheric vignettes, each headed by a relevant word or phrase in the Shaetlan dialect. Hadfield, who is British Canadian, moved to the islands in her late twenties in 2006 and soon found her niche. “My new life quickly debunked those Edge-of-the-World myths – Shetland was too busy to feel remote, and had too strong a sense of its own identity to feel frontier-like.” It’s gently ironic, she notes, that she’s a terrible sailor and gets vertigo at height yet lives somewhere with perilous cliff edges that is often reachable only by sea. Living in a trailer waiting for her home to be built on West Burra, she feels the line between indoors and out is especially thin. It’s a life of wild swimming, beachcombing, fresh fish, folk music, seabirds, kind neighbours, and good cheer that warms long winter nights. After the isolation of the pandemic period comes the unexpected joy of a partner and a pregnancy in her mid-forties. Hadfield is a Windham-Campbell Prize-winning poet, and her lyrical prose is full of lovely observations that made me hanker to return to Shetland – it’s been 19 years since my only visit, after all. This was a slow read I savoured for its language and sense of place.

This is not so much a straightforward memoir as a set of atmospheric vignettes, each headed by a relevant word or phrase in the Shaetlan dialect. Hadfield, who is British Canadian, moved to the islands in her late twenties in 2006 and soon found her niche. “My new life quickly debunked those Edge-of-the-World myths – Shetland was too busy to feel remote, and had too strong a sense of its own identity to feel frontier-like.” It’s gently ironic, she notes, that she’s a terrible sailor and gets vertigo at height yet lives somewhere with perilous cliff edges that is often reachable only by sea. Living in a trailer waiting for her home to be built on West Burra, she feels the line between indoors and out is especially thin. It’s a life of wild swimming, beachcombing, fresh fish, folk music, seabirds, kind neighbours, and good cheer that warms long winter nights. After the isolation of the pandemic period comes the unexpected joy of a partner and a pregnancy in her mid-forties. Hadfield is a Windham-Campbell Prize-winning poet, and her lyrical prose is full of lovely observations that made me hanker to return to Shetland – it’s been 19 years since my only visit, after all. This was a slow read I savoured for its language and sense of place. ![]()

With thanks to Picador for the free paperback copy for review.

From Shetland authors, I have also reviewed:

Orchid Summer by Jon Dunn (Hadfield mentions him)

Sea Bean by Sally Huband (Hadfield meets her)

The Valley at the Centre of the World by Malachy Tallack

Moving Mountains: Writing Nature through Illness and Disability, ed. Louise Kenward (2023)

I often read memoirs about chronic illness and disability – the sort of narratives recognized by the Barbellion and ACDI Literary Prizes – and the idea of nature essays that reckon with health limitations was an irresistible draw. The quality in this anthology varies widely, from excellent to barely readable (for poor prose or pretentiousness). I’ll be kind and not name names in the latter category; I’ll only say the book has been poorly served by the editing process. The best material is generally from authors with published books: Polly Atkin (Some of Us Just Fall; see also her recent response to the Raynor Winn fiasco), Victoria Bennett (All My Wild Mothers), Sally Huband (as above!), and Abi Palmer (Sanatorium). For the first three, the essay feels like an extension of their memoir, while Palmer’s inventive piece is about recreating seasons for her indoor cats. My three favourite entries, however, were Louisa Adjoa Parker’s poem “This Is Not Just Tired,” Nic Wilson’s “A Quince in the Hand” (she’s an acquaintance through New Networks for Nature and has a memoir out this summer, Land Beneath the Waves), and Eli Clare’s “Moving Close to the Ground,” about being willing to scoot and crawl to get into nature. A number of the other pieces are repetitive, overlong or poorly shaped and don’t integrate information about illness in a natural way. Kudos to Kenward for including BIPOC and trans/queer voices, though. (Christmas gift from my wish list)

I often read memoirs about chronic illness and disability – the sort of narratives recognized by the Barbellion and ACDI Literary Prizes – and the idea of nature essays that reckon with health limitations was an irresistible draw. The quality in this anthology varies widely, from excellent to barely readable (for poor prose or pretentiousness). I’ll be kind and not name names in the latter category; I’ll only say the book has been poorly served by the editing process. The best material is generally from authors with published books: Polly Atkin (Some of Us Just Fall; see also her recent response to the Raynor Winn fiasco), Victoria Bennett (All My Wild Mothers), Sally Huband (as above!), and Abi Palmer (Sanatorium). For the first three, the essay feels like an extension of their memoir, while Palmer’s inventive piece is about recreating seasons for her indoor cats. My three favourite entries, however, were Louisa Adjoa Parker’s poem “This Is Not Just Tired,” Nic Wilson’s “A Quince in the Hand” (she’s an acquaintance through New Networks for Nature and has a memoir out this summer, Land Beneath the Waves), and Eli Clare’s “Moving Close to the Ground,” about being willing to scoot and crawl to get into nature. A number of the other pieces are repetitive, overlong or poorly shaped and don’t integrate information about illness in a natural way. Kudos to Kenward for including BIPOC and trans/queer voices, though. (Christmas gift from my wish list) ![]()

The Stirrings: Coming of Age in Northern Time by Catherine Taylor (2023)

“A typical family and an ordinary story, although neither the family nor the story seems commonplace when it is your family and your story.”

Taylor, who was born in New Zealand and grew up in Sheffield, won the Ackerley Prize for this memoir. (After Dunmore and King, this is the third in my intended four-in-a-row on the 20 Books of Summer Bingo card, fulfilling the “Book published in summer” category – August 2023.) It is bookended by two pivotal summers: 1976, the last normal season in her household before her father left; and 1989, the “Second Summer of Love,” when she had an abortion (the subject of “Milk Teeth,” the best individual chapter and a strong stand-alone essay). In between, fear and outrage overshadow her life: the Yorkshire Ripper is at large, nuclear war looms, mines are closing and protesters meet with harsh reprisals, and her own health falters until she gets a diagnosis of Graves’ disease. Then, in her final year at Cardiff, one of their housemates is found dead. Taylor draws reasonably subtle links to the present day, when fascism, global threats, and femicide are, unfortunately, as timely as ever. She’s the sort of personality I see at every London literary event I attend: Wellcome Book Prize ceremonies, Weatherglass’s Future of the Novella event, and so on. I got the feeling this book is more about bearing witness to history than revealing herself, and so I never warmed to it or to her on the page. But if you’d like to get a feel for the mood of the times, or you have experience of the settings and period, you may well enjoy it more than I did. (New purchase from Bookshop.org with a Christmas book token)

Taylor, who was born in New Zealand and grew up in Sheffield, won the Ackerley Prize for this memoir. (After Dunmore and King, this is the third in my intended four-in-a-row on the 20 Books of Summer Bingo card, fulfilling the “Book published in summer” category – August 2023.) It is bookended by two pivotal summers: 1976, the last normal season in her household before her father left; and 1989, the “Second Summer of Love,” when she had an abortion (the subject of “Milk Teeth,” the best individual chapter and a strong stand-alone essay). In between, fear and outrage overshadow her life: the Yorkshire Ripper is at large, nuclear war looms, mines are closing and protesters meet with harsh reprisals, and her own health falters until she gets a diagnosis of Graves’ disease. Then, in her final year at Cardiff, one of their housemates is found dead. Taylor draws reasonably subtle links to the present day, when fascism, global threats, and femicide are, unfortunately, as timely as ever. She’s the sort of personality I see at every London literary event I attend: Wellcome Book Prize ceremonies, Weatherglass’s Future of the Novella event, and so on. I got the feeling this book is more about bearing witness to history than revealing herself, and so I never warmed to it or to her on the page. But if you’d like to get a feel for the mood of the times, or you have experience of the settings and period, you may well enjoy it more than I did. (New purchase from Bookshop.org with a Christmas book token) ![]()

Three Days in June vs. Three Weeks in July

Two very good 2025 releases that I read from the library. While they could hardly be more different in tone and particulars, I couldn’t resist linking them via their titles.

Three Days in June by Anne Tyler

(From my Most Anticipated list.) A delightful little book that I loved more than I expected to, for several reasons: the effective use of a wedding weekend as a way of examining what goes wrong in marriages and what we choose to live with versus what we can’t forgive; Gail’s first-person narration, a rarity for Tyler* and a decision that adds depth to what might otherwise have been a two-dimensional depiction of a woman whose people skills leave something to be desired; and the unexpected presence of a cat who brings warmth and caprice back into her home. (I read this soon after losing my old cat, and it was comforting to be reminded that cats and their funny ways are the same the world over.)

From Tyler’s oeuvre, this reminded me most of The Amateur Marriage and has a surprise Larry’s Party-esque ending. The discussion of the outmoded practice of tapping one’s watch is a neat tie-in to her recurring theme of the nature of time. And through the lunch out at a chic crab restaurant, she succeeds at making the Baltimore setting essential rather than incidental, more so than in much of her other work.

Gail is in the sandwich generation with a daughter just married and an old mother who’s just about independent. I appreciated that she’s 61 and contemplating retirement, but still feels as if she hasn’t a clue: “What was I supposed to do with the rest of my life? I’m too young for this, I thought. Not too old, as you might expect, but too young, too inept, too uninformed. How come there weren’t any grownups around? Why did everyone just assume I knew what I was doing?”

My only misgiving is that Tyler doesn’t quite get it right about the younger generation: women who are in their early thirties in 2023 (so born about 1990) wouldn’t be called Debbie and Bitsy. To some degree, Tyler’s still stuck back in the 1970s, but her observations about married couples and family dynamics are as shrewd as ever. Especially because of the novella length, I can recommend this to readers wanting to try Tyler for the first time. ![]()

*I’ve noted it in Earthly Possessions. Anywhere else?

Three Weeks in July: 7/7, The Aftermath, and the Deadly Manhunt by Adam Wishart and James Nally

July 7th is my wedding anniversary but before that, and ever since, it’s been known as the date of the UK’s worst terrorist attack, a sort of lesser 9/11 – and while reading this I felt the same way that I’ve felt reading books about 9/11: a sort of awed horror. Suicide bombers who were born in the UK but radicalized on trips to Islamic training camps in Pakistan set off explosions on three Underground trains and one London bus. I didn’t think my memories of 7/7 were strong, yet some names were incredibly familiar to me (chiefly Mohammad Sidique Khan, the leader of the attacks; Jean Charles de Menezes, the innocent Brazilian electrician shot dead on a Tube train when confused with a suspect in the 21/7 copycat plot – police were operating under a new shoot-to-kill policy and this was the tragic result).

Fifty-two people were killed that day, ranging in age from 20 to 60; 20 were not UK citizens, hailing from everywhere from Grenada to Mauritius. But a total of 770 people were injured. I found the authors’ recreation of events very gripping, though do be warned that there is a lot of gruesome medical and forensic detail about fatalities and injuries. They humanize the scale of events and make things personal by focusing on four individuals who were injured, even losing multiple limbs in some cases, but survived and now work in motivational speaking, disability services or survivor advocacy.

Fifty-two people were killed that day, ranging in age from 20 to 60; 20 were not UK citizens, hailing from everywhere from Grenada to Mauritius. But a total of 770 people were injured. I found the authors’ recreation of events very gripping, though do be warned that there is a lot of gruesome medical and forensic detail about fatalities and injuries. They humanize the scale of events and make things personal by focusing on four individuals who were injured, even losing multiple limbs in some cases, but survived and now work in motivational speaking, disability services or survivor advocacy.

What really got to me was thinking about all the hundreds of people who, 20 years on, still live with permanent pain, disability or grief because of the randomness of them or their loved ones getting caught up in a few misguided zealots’ plot. One detail that particularly struck me: with the Tube tunnels closed off at both ends while searchers recovered bodies, the temperature rose to 50 degrees C (122 degrees F), only exacerbating the stench. The book mostly avoids cliches and overwriting, though I did find myself skimming in places. It is based on the research done for a BBC documentary series and synthesizes a lot of material in an engaging way that does justice to the victims. ![]()

Have you read one or both of these?

Could you see yourself picking one of them up?

Three on a Theme for Father’s Day: Holt Poetry, Filgate & Virago Anthologies

A rare second post in a day for me; I got behind with my planned cat book reviews. I happen to have had a couple of fatherhood-themed books come my way earlier this year, an essay anthology and a debut poetry collection. To make it a trio, I finished an anthology of autobiographical essays about father–daughter relationships that I’d started last year.

What My Father and I Don’t Talk About: Sixteen Writers Break the Silence, ed. Michele Filgate (2025)

This follow-up to Michele Filgate’s What My Mother and I Don’t Talk About is an anthology of 16 compassionate, nuanced essays probing the intricacies of family relationships.

Understanding a father’s background can be the key to interpreting his later behavior. Isle McElroy had to fight for scraps of attention from their electrician father, who grew up in foster care; Susan Muaddi Darraj’s Palestinian father was sent to America to make money to send home. Such experiences might explain why the men were unreliable or demanding as adults. Patterns threaten to repeat across the generations: Andrew Altschul realizes his father’s hands-off parenting (he joked he’d changed a diaper “once”) was an outmoded convention he rejects in raising his own son; Jaquira Díaz learns that the depression she and her father battle stemmed from his tragic loss of his first family.

Understanding a father’s background can be the key to interpreting his later behavior. Isle McElroy had to fight for scraps of attention from their electrician father, who grew up in foster care; Susan Muaddi Darraj’s Palestinian father was sent to America to make money to send home. Such experiences might explain why the men were unreliable or demanding as adults. Patterns threaten to repeat across the generations: Andrew Altschul realizes his father’s hands-off parenting (he joked he’d changed a diaper “once”) was an outmoded convention he rejects in raising his own son; Jaquira Díaz learns that the depression she and her father battle stemmed from his tragic loss of his first family.

Some take the title brief literally: Heather Sellers dares to ask her father about his cross-dressing when she visits him in a nursing home; Nayomi Munaweera is pleased her 82-year-old father can escape his arranged marriage, but the domestic violence that went on in it remains unspoken. Tomás Q. Morín’s “Operation” has the most original structure, with the board game’s body parts serving as headings. All the essays display psychological insight, but Alex Marzano-Lesnevich’s—contrasting their father’s once-controlling nature with his elderly vulnerability—is the pinnacle.

Despite the heavy topics—estrangement, illness, emotional detachment—these candid pieces thrill with their variety and their resonant themes. (Read via Edelweiss)

Reprinted with permission from Shelf Awareness. (The above is my unedited version.)

Father’s Father’s Father by Dane Holt (2025)

Holt’s debut collection interrogates masculinity through poems about bodybuilders and professional wrestlers, teenage risk-taking and family misdemeanours.

Your father’s father’s father

poisoned a beautiful horse,

that’s the story. Now you know this

you’ve opened the door marked

‘Family History’.

(from “‘The Granaries are Bursting with Meal’”)

The only records found in my grandmother’s attic

were by scorned women for scorned women

written by men.

(from “Tammy Wynette”)

He writes in the wake of the deaths of his parents, which, as W.S. Merwin observed, makes one feel, “I could do anything,” – though here the poet concludes, “The answer can be nothing.” Stylistically, the collection is more various than cohesive, with some of the late poetry as absurdist as you find in Caroline Bird’s. My favourite poem is “Humphrey Bogart,” with its vision of male toughness reinforced by previous generations’ emotional repression:

My grandfather

never told his son that he loved him.

I said this to a group of strangers

and then said, Consider this:

his son never asked to be told.

They both loved

the men Humphrey Bogart played.

…

There was

one thing my grandfather could

not forgive his son for.

Eventually it was his son’s dying, yes.

With thanks to Carcanet Press for the free e-copy for review.

Fathers: Reflections by Daughters, ed. Ursula Owen (1983; 1994)

“I doubt if my father will ever lose his power to wound me, and yet…”

~Eileen Fairweather

I read the introduction and first seven pieces (one of them a retelling of a fairy tale) last year and reviewed that first batch here. Some common elements I noted in those were service in a world war, Freudian interpretation, and the alignment of the father with God. The writers often depicted their fathers as unknown, aloof, or as disciplinarians. In the remainder of the book, I particularly noted differences in generations and class. Father and daughter are often separated by 40–55 years. The men work in industry; their daughters turn to academia. Her embrace of radicalism or feminism can alienate a man of conservative mores.

Sometimes a father is defined by his emotional or literal absence. Dinah Brooke addresses her late father directly: “Obsessed with you for years, but blind – seeing only the huge holes you had left in my life, and not you at all. … I did so want someone to be a father to me. You did the best you could. It wasn’t a lot. The desire was there, but the execution was feeble.” Had Mary Gordon been tempted to romanticize her father, who died when she was seven, that aim was shattered when she learned how much he’d lied about and read his reactionary and ironically antisemitic writings (given that he was a Jew who converted to Catholicism).

Sometimes a father is defined by his emotional or literal absence. Dinah Brooke addresses her late father directly: “Obsessed with you for years, but blind – seeing only the huge holes you had left in my life, and not you at all. … I did so want someone to be a father to me. You did the best you could. It wasn’t a lot. The desire was there, but the execution was feeble.” Had Mary Gordon been tempted to romanticize her father, who died when she was seven, that aim was shattered when she learned how much he’d lied about and read his reactionary and ironically antisemitic writings (given that he was a Jew who converted to Catholicism).

I mostly skipped over the quotes from novels and academic works printed between the essays. There are solid pieces by Adrienne Rich, Michèle Roberts, Sheila Rowbotham, and Alice Walker, but Alice Munro knocks all the other contributors into a cocked hat with “Working for a Living,” which is as detailed and psychologically incisive as one of her stories (cf. The Beggar Maid with its urban/rural class divide). Her parents owned a fox farm but, as it failed, her father took a job as night watchman at a factory. She didn’t realize, until one day when she went in person to deliver a message, that he was a janitor there as well.

This was a rewarding collection to read and I will keep it around for models of autobiographical writing, but it now feels like a period piece: the fact that so many of the fathers had lived through the world wars, I think, might account for their cold and withdrawn nature – they were damaged, times were tough, and they believed they had to be an authority figure. Things have changed, somewhat, as the Filgate anthology reflects, though father issues will no doubt always be with us. (Secondhand – National Trust bookshop)

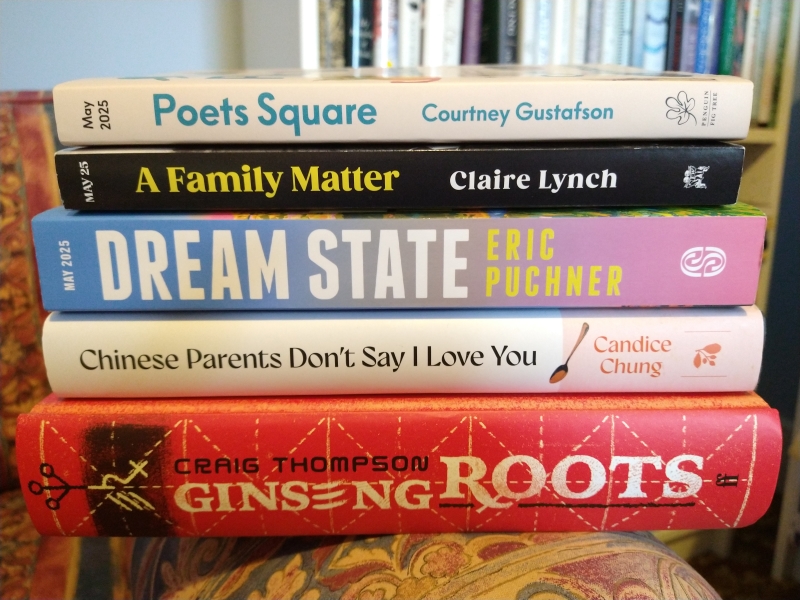

#ReadingtheMeow2025, Part I: Books by Gustafson, Inaba, Tomlinson and More

It’s the start of the third annual week-long Reading the Meow challenge, hosted by Mallika of Literary Potpourri! For my first set of reviews, I have two lovely memoirs of life with cats, and a few cute children’s books.

Poets Square: A Memoir in Thirty Cats by Courtney Gustafson (2025)

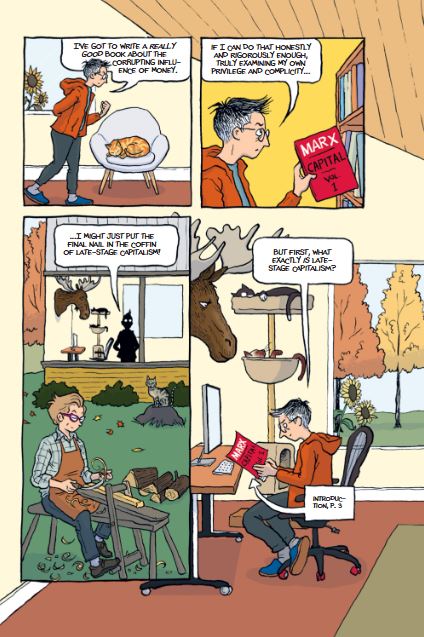

This was on my Most Anticipated list and surpassed my expectations. Because I’m a snob and knew only that the author was a young influencer, I was pleasantly surprised by the quality of the prose and the depth of the social analysis. After Gustafson left academia, she became trapped in a cycle of dead-end jobs and rising rents. Working for a food bank, she saw firsthand how broken systems and poverty wear people down. She’d recently started feeding and getting veterinary care for the 30 feral cats of a colony in her Poets Square neighbourhood in Tucson, Arizona. They all have unique personalities and interactions, such as Sad Boy and Lola, a loyal bonded pair; and MK, who made Georgie her surrogate baby. Gustafson doled out quirky names and made the cats Instagram stars (@PoetsSquareCats). Soon she also became involved in other local trap, neuter and release initiatives.

That the German translation is titled “Cats and Capitalism” gives an idea of how the themes are linked here: cat colonies tend to crop up where deprivation prevails. Stray cats, who live short and difficult lives, more reliably receive compassion than struggling people for whom the same is true. TNR work takes Gustafson to places where residents are only just clinging on to solvency or where hoarding situations have gotten out of control. I also appreciated a chapter that draws a parallel between how she has been perceived as a young woman and how female cats are deemed “slutty.” (Having a cat spayed so she does not undergo constant pregnancies is a kindness.) She also interrogates the “cat mom” stereotype through an account of her relationship with her mother and her own decision not to have children.

Gustafson knows how lucky she is to have escaped a paycheck-to-paycheck existence. Fame came seemingly out of nowhere when a TikTok video she posted about preparing a mini Thanksgiving dinner for the cats went viral. Social media and cat rescue work helped a shy, often ill person be less lonely, giving her “a community, a sense of rootedness, a purpose outside myself.” (Moreover, her Internet following literally ensured she had a place to live: when her rental house was being sold out from under her, a crowdfunding campaign allowed her to buy the house and save the cats.) However, they have also made her aware of a “constant undercurrent of suffering.” There are multiple cat deaths in the book, as you might expect. The author has become inured over time; she allows herself five minutes to cry, then moves on to help other cats. It’s easy to be overwhelmed or succumb to despair, but she chooses to focus on the “small acts of care by people trying hard” that can reduce suffering.

With its radiant portraits of individual cats and its realistic perspective on personal and collective problems, this is both a cathartic memoir and a probing study of how we build communities of care in times of hardship.

With thanks to Fig Tree (Penguin) for the proof copy for review.

Mornings without Mii by Mayumi Inaba (1999; 2024)

[Translated from Japanese by Ginny Tapley Takemori]

Inaba (1950–2014) was an award-winning novelist and poet. I can’t think why it took 25 years for this to be translated into English but assume it was considered a minor work of hers and was brought out to capitalize on the continuing success of cat-themed Japanese literature from The Guest Cat onward. Interestingly, it’s titled Mornings with Mii in the UK, which shifts the focus and is truer to the contents. Yes, by the end, Inaba is without Mii and dreading the days ahead, but before that she got 20 years of companionship. One day in the summer of 1977, Inaba heard a kitten’s cries on the breeze and finally located it, stuck so high in a school fence that someone must have left her there deliberately. The little fleabitten calico was named after the sound of her cry and ever after was afraid of heights.

Inaba traces the turning of the seasons and the passing of the years through the changes they brought for her and for Mii. When she separated, moved to a new part of Tokyo, and started devoting her evenings to writing in addition to her full-time job, Mii was her closest friend. The new apartment didn’t have any green space, so instead of wandering in the woods Mii had to get used to exercising in the corridors. There were some scares: a surprise pregnancy nearly killed her, and once she went missing. And then there was the inevitable decline. Mii’s intestinal issues led to incontinence. For four years, Inaba endured her home reeking of urine. Many readers may, like me, be taken aback by how long Inaba kept Mii alive. She manually assisted the cat with elimination for years; 20 days passed between when Mii stopped eating and when she died. On the plus side, she got a “natural” death at home, but her quality of life in these years is somewhat alarming. I cried buckets through these later chapters, thinking of the friendship and intimate communion I had with Alfie. I can understand why Inaba couldn’t bear to say goodbye to Mii any earlier, especially because she’d lived alone since her divorce.

Inaba traces the turning of the seasons and the passing of the years through the changes they brought for her and for Mii. When she separated, moved to a new part of Tokyo, and started devoting her evenings to writing in addition to her full-time job, Mii was her closest friend. The new apartment didn’t have any green space, so instead of wandering in the woods Mii had to get used to exercising in the corridors. There were some scares: a surprise pregnancy nearly killed her, and once she went missing. And then there was the inevitable decline. Mii’s intestinal issues led to incontinence. For four years, Inaba endured her home reeking of urine. Many readers may, like me, be taken aback by how long Inaba kept Mii alive. She manually assisted the cat with elimination for years; 20 days passed between when Mii stopped eating and when she died. On the plus side, she got a “natural” death at home, but her quality of life in these years is somewhat alarming. I cried buckets through these later chapters, thinking of the friendship and intimate communion I had with Alfie. I can understand why Inaba couldn’t bear to say goodbye to Mii any earlier, especially because she’d lived alone since her divorce.

This memoir really captures the mixture of joy and heartache that comes with loving a pet. It’s an emotional connection that can take over your life in a good way but leave you bereft when it’s gone. There is nostalgia for the good days with Mii, but also regret and a heavy sense of responsibility. A number of the chapters end with a poem about Mii, but the prose, too, has haiku-like elegance and simplicity. It’s a beautiful book I can strongly recommend. (Read via Edelweiss)

let’s sleep

So as not to hear your departing footsteps

She won’t be here next year I know

I know we won’t have this time again

On this bright afternoon overcome with an unfathomable sadness

The greenery shines in my cat’s gentle eyes

I didn’t have any particular faith, but the one thing I did believe in was light. Just being in warm light, I could be with the people and the cat I had lost from my life. My mornings without Mii would start tomorrow. … Mii had returned to the light, and I would still be able to meet her there hundreds, thousands of times again.

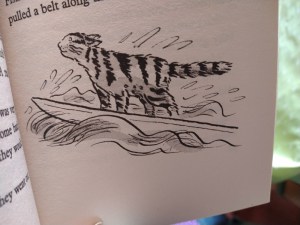

The Cat Who Wanted to Go Home by Jill Tomlinson (1972)

Suzy the cat lives in a French seaside village with a fisherman and his family of four sons. One day, she curls up to sleep in a basket only to wake up airborne – it’s a hot air balloon, taking her to England! Here the RSPCA place her with old Auntie Jo, who feeds her well, but Suzy longs to get back home. “Chez-moi” is her constant cry, which everyone thinks is an awfully funny way to say miaow (“She purred in French, [too,] but purring sounds the same all over the world”). Each day she hops into the basket of Auntie Jo’s bike for a ride to town to try a new route over the sea: in a kayak, on a surfboard, paddling alongside a Channel swimmer, and so on. Each attempt fails and she returns to her temporary lodgings: shared with a parrot named Biff and comfortable, yet not quite right. Until one day… This is a sweet little story (a 77-page paperback) for new readers to experience along with a parent, with just enough repetition to be soothing and a reassuring message about the benevolence of strangers. Susan Hellard’s illustrations are charming. (Secondhand – local library book sale)

Suzy the cat lives in a French seaside village with a fisherman and his family of four sons. One day, she curls up to sleep in a basket only to wake up airborne – it’s a hot air balloon, taking her to England! Here the RSPCA place her with old Auntie Jo, who feeds her well, but Suzy longs to get back home. “Chez-moi” is her constant cry, which everyone thinks is an awfully funny way to say miaow (“She purred in French, [too,] but purring sounds the same all over the world”). Each day she hops into the basket of Auntie Jo’s bike for a ride to town to try a new route over the sea: in a kayak, on a surfboard, paddling alongside a Channel swimmer, and so on. Each attempt fails and she returns to her temporary lodgings: shared with a parrot named Biff and comfortable, yet not quite right. Until one day… This is a sweet little story (a 77-page paperback) for new readers to experience along with a parent, with just enough repetition to be soothing and a reassuring message about the benevolence of strangers. Susan Hellard’s illustrations are charming. (Secondhand – local library book sale)

And a couple of other children’s books:

Mittens for Kittens and Other Rhymes about Cats, ed. Lenore Blegvad; illus. Erik Blegvad (1974) – A selection of traditional English and Scottish nursery rhymes, a few of them true to the nature of cats but most of them just nonsensical. You’ve got to love the drawings, though. (Secondhand – Hay Castle honesty shelves)

Mittens for Kittens and Other Rhymes about Cats, ed. Lenore Blegvad; illus. Erik Blegvad (1974) – A selection of traditional English and Scottish nursery rhymes, a few of them true to the nature of cats but most of them just nonsensical. You’ve got to love the drawings, though. (Secondhand – Hay Castle honesty shelves)

Scaredy Cat by Stuart Trotter (2007) – Rhyming couplets about everyday childhood fears and what makes them better. I thought it unfortunate that the young cat is afraid of other creatures; to be afraid of dogs is understandable, but three pages about not liking invertebrates is the wrong message to be sending. (Little Free Library)

Scaredy Cat by Stuart Trotter (2007) – Rhyming couplets about everyday childhood fears and what makes them better. I thought it unfortunate that the young cat is afraid of other creatures; to be afraid of dogs is understandable, but three pages about not liking invertebrates is the wrong message to be sending. (Little Free Library)

Although her choices are indisputable classics, she acknowledges they can only ever be an incomplete and biased selection, unfortunately all white and largely male, though she opens with

Although her choices are indisputable classics, she acknowledges they can only ever be an incomplete and biased selection, unfortunately all white and largely male, though she opens with

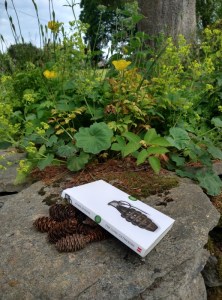

Rightly likened to Of Mice and Men, this is an engrossing short novel about two brothers, Neil and Calum, tasked with climbing trees and gathering the pinecones of a wealthy Scottish estate. They will be used to replant the many woodlands being cut down to fuel the war effort. Calum, the younger brother, is physically and intellectually disabled but has a deep well of compassion for living creatures. He has unwittingly made an enemy of the estate’s gamekeeper, Duror, by releasing wounded rabbits from his traps. Much of the story is taken up with Duror’s seemingly baseless feud against the brothers – though we’re meant to understand that his bedbound wife’s obesity and his subsequent sexual frustration may have something to do with it – as well as with Lady Runcie-Campbell’s class prejudice. Her son, Roderick, is an unexpected would-be hero and voice of pure empathy. I read this quickly, with grim fascination, knowing tragedy was coming but not quite how things would play out. The introduction to Canongate’s Canons Collection edition is by actor Paul Giamatti, of all people. (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project, Newbury)

Rightly likened to Of Mice and Men, this is an engrossing short novel about two brothers, Neil and Calum, tasked with climbing trees and gathering the pinecones of a wealthy Scottish estate. They will be used to replant the many woodlands being cut down to fuel the war effort. Calum, the younger brother, is physically and intellectually disabled but has a deep well of compassion for living creatures. He has unwittingly made an enemy of the estate’s gamekeeper, Duror, by releasing wounded rabbits from his traps. Much of the story is taken up with Duror’s seemingly baseless feud against the brothers – though we’re meant to understand that his bedbound wife’s obesity and his subsequent sexual frustration may have something to do with it – as well as with Lady Runcie-Campbell’s class prejudice. Her son, Roderick, is an unexpected would-be hero and voice of pure empathy. I read this quickly, with grim fascination, knowing tragedy was coming but not quite how things would play out. The introduction to Canongate’s Canons Collection edition is by actor Paul Giamatti, of all people. (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project, Newbury)

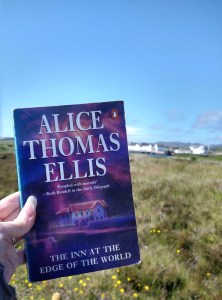

Eric and Mabel moved from the Midlands to run a hotel on a remote Scottish island. He places an advertisement in select London periodicals to lure in some Christmas-haters for the holidays and attracts a motley group: a bereaved former soldier writing a biography of General Gordon, a pair of actors known only for commercials, a psychoanalyst, and a department store buyer looking for a novel sweater pattern. Mabel decides she’s had enough and flees the island just as the guests start arriving. One guest is stalking another; one has history on the island. And all along, there are hints that this is a site of major selkie activity. I found it jarring how the novella moved from Shena Mackay-like social comedy into magic realism and doubt I’ll read more by Ellis (I’d already read one volume of

Eric and Mabel moved from the Midlands to run a hotel on a remote Scottish island. He places an advertisement in select London periodicals to lure in some Christmas-haters for the holidays and attracts a motley group: a bereaved former soldier writing a biography of General Gordon, a pair of actors known only for commercials, a psychoanalyst, and a department store buyer looking for a novel sweater pattern. Mabel decides she’s had enough and flees the island just as the guests start arriving. One guest is stalking another; one has history on the island. And all along, there are hints that this is a site of major selkie activity. I found it jarring how the novella moved from Shena Mackay-like social comedy into magic realism and doubt I’ll read more by Ellis (I’d already read one volume of

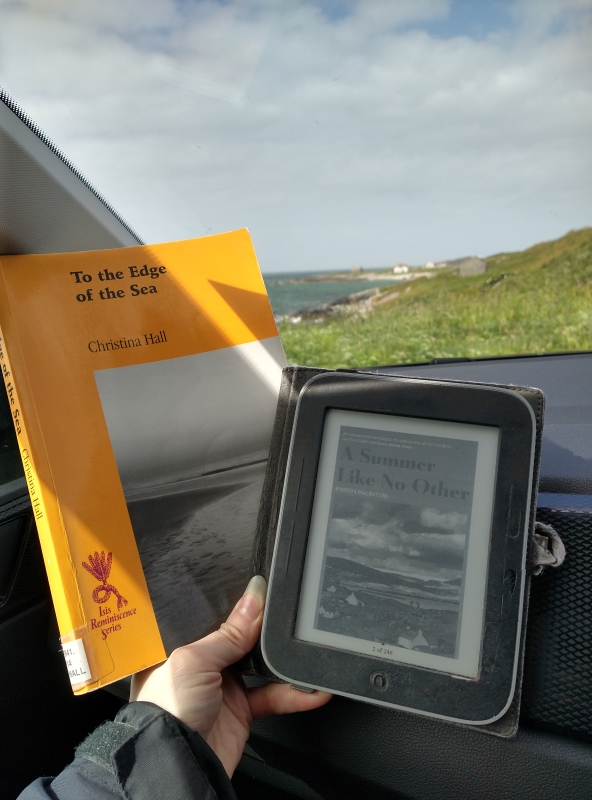

The many Gaelic phrases, defined in footnotes, help to create the atmosphere. The chapter epigraphs from the legend of Oisín (son of Fionn Mac Cumhaill) and Tír Na nÓg, the land of eternal youth, heighten the contrast between Colin’s idealism and the reality of this life-changing season. I think this is the first book I’ve read that was originally published in Gaelic and I hope it will find readers far beyond its island niche. (BookSirens)

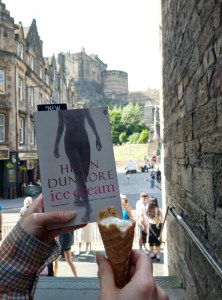

The many Gaelic phrases, defined in footnotes, help to create the atmosphere. The chapter epigraphs from the legend of Oisín (son of Fionn Mac Cumhaill) and Tír Na nÓg, the land of eternal youth, heighten the contrast between Colin’s idealism and the reality of this life-changing season. I think this is the first book I’ve read that was originally published in Gaelic and I hope it will find readers far beyond its island niche. (BookSirens)  1) Our transit through Edinburgh was brief and muggy, but we made sure to leave just enough time to queue for cones at Mary’s Milk Bar, which has the most interesting flavours you’ll find anywhere. Pictured, though half eaten, are my one scoop of Earl Grey and peach sorbet and one scoop of fig and cardamom ice cream. When we returned to Edinburgh to return the car at the end of our trip, I took the train home by myself but C stayed on for a conference, during which he treated himself to another round at Mary’s.

1) Our transit through Edinburgh was brief and muggy, but we made sure to leave just enough time to queue for cones at Mary’s Milk Bar, which has the most interesting flavours you’ll find anywhere. Pictured, though half eaten, are my one scoop of Earl Grey and peach sorbet and one scoop of fig and cardamom ice cream. When we returned to Edinburgh to return the car at the end of our trip, I took the train home by myself but C stayed on for a conference, during which he treated himself to another round at Mary’s.

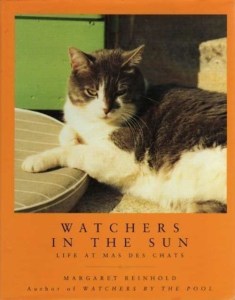

A quaint short memoir set in the 1950s on the island of Mull (which we sailed past on our way to and from the Outer Hebrides). It’s narrated in tongue-in-cheek fashion by Nicholas the Cat, who pals around with the farm’s dogs, horse and goats and comments on the doings of its human inhabitants, such as “Puddy” (Carothers), a war widow, and her daughter Fionna, who goes away to school. “We understand so much about them, yet they understand so little about us,” he opines. Indeed, the animals are all observant and can communicate with each other. Corrieshellach is a fine horse taken to compete in shows. The goats are lucky to escape with their lives after a local outbreak of foot-and-mouth disease among livestock. Nicholas grows fat on rabbits and fathers several litters. He voices some traditional views (the Clearances: bad but the Empire: good; crows: bad); then again, cats would certainly be C/conservatives. A sweet Blyton-esque read for precocious children or sentimental adults, this passed the time nicely on a long drive. It could do with a better title, though; the ducks only play a tiny role. (Favourite aside: “that beverage which humans find so comforting when things aren’t right. Tea.”) (Secondhand – Benbecula thrift shop)

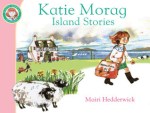

A quaint short memoir set in the 1950s on the island of Mull (which we sailed past on our way to and from the Outer Hebrides). It’s narrated in tongue-in-cheek fashion by Nicholas the Cat, who pals around with the farm’s dogs, horse and goats and comments on the doings of its human inhabitants, such as “Puddy” (Carothers), a war widow, and her daughter Fionna, who goes away to school. “We understand so much about them, yet they understand so little about us,” he opines. Indeed, the animals are all observant and can communicate with each other. Corrieshellach is a fine horse taken to compete in shows. The goats are lucky to escape with their lives after a local outbreak of foot-and-mouth disease among livestock. Nicholas grows fat on rabbits and fathers several litters. He voices some traditional views (the Clearances: bad but the Empire: good; crows: bad); then again, cats would certainly be C/conservatives. A sweet Blyton-esque read for precocious children or sentimental adults, this passed the time nicely on a long drive. It could do with a better title, though; the ducks only play a tiny role. (Favourite aside: “that beverage which humans find so comforting when things aren’t right. Tea.”) (Secondhand – Benbecula thrift shop)  I read half of this large-format paperback before our trip and the rest afterward. It collects four of Hedderwick’s picture books, which are all set on the Isle of Struay, a kind of Hebridean composite that reproduces the islands’ wildlife and scenery beautifully. Katie Morag’s parents run the shop and post office and her mother always seems to be producing another little brother. In Katie Morag Delivers the Mail, the little red-haired girl causes chaos by delivering parcels at random. Sophisticated Granma Mainland and practical Grannie Island are the stars of Katie Morag and the Two Grandmothers. Katie Morag learns to deal with her anger and with being punished, respectively, in …and the Tiresome Ted and …and the Big Boy Cousins. Cute stories with useful lessons, but the illustrations are the main attraction. I’ll get the rest of the books out from the library. (Little Free Library)

I read half of this large-format paperback before our trip and the rest afterward. It collects four of Hedderwick’s picture books, which are all set on the Isle of Struay, a kind of Hebridean composite that reproduces the islands’ wildlife and scenery beautifully. Katie Morag’s parents run the shop and post office and her mother always seems to be producing another little brother. In Katie Morag Delivers the Mail, the little red-haired girl causes chaos by delivering parcels at random. Sophisticated Granma Mainland and practical Grannie Island are the stars of Katie Morag and the Two Grandmothers. Katie Morag learns to deal with her anger and with being punished, respectively, in …and the Tiresome Ted and …and the Big Boy Cousins. Cute stories with useful lessons, but the illustrations are the main attraction. I’ll get the rest of the books out from the library. (Little Free Library)

The only name on the cover is Lulu Mayo, who does the illustrations. That’s your clue that the text (by Justine Solomons-Moat) is pretty much incidental; this is basically a YA mini coffee table book. I found it pleasant enough to read bits of at bedtime but it’s not about to win any prizes. (I mean, it prints “prolificate” twice; that ain’t a word. Proliferate is.) Among the famous cat ladies given one-page profiles are Georgia O’Keeffe, Jacinda Ardern, Vivien Leigh, and Anne Frank. I hadn’t heard of the Scottish Fold cat breed, but now I know that they’ve become popular thanks Taylor Swift. The few informational interludes are pretty silly, though I did actually learn that a cat heads straight for the non-cat person in the room (like our friend Steve) because they find eye contact with strangers challenging so find the person who’s ignoring them the least threatening. I liked the end of the piece on Judith Kerr: “To her, cats were symbols of home, sources of inspiration and constant companions. It’s no wonder that she once observed, ‘they’re very interesting people, cats.’” (Christmas gift, secondhand)

The only name on the cover is Lulu Mayo, who does the illustrations. That’s your clue that the text (by Justine Solomons-Moat) is pretty much incidental; this is basically a YA mini coffee table book. I found it pleasant enough to read bits of at bedtime but it’s not about to win any prizes. (I mean, it prints “prolificate” twice; that ain’t a word. Proliferate is.) Among the famous cat ladies given one-page profiles are Georgia O’Keeffe, Jacinda Ardern, Vivien Leigh, and Anne Frank. I hadn’t heard of the Scottish Fold cat breed, but now I know that they’ve become popular thanks Taylor Swift. The few informational interludes are pretty silly, though I did actually learn that a cat heads straight for the non-cat person in the room (like our friend Steve) because they find eye contact with strangers challenging so find the person who’s ignoring them the least threatening. I liked the end of the piece on Judith Kerr: “To her, cats were symbols of home, sources of inspiration and constant companions. It’s no wonder that she once observed, ‘they’re very interesting people, cats.’” (Christmas gift, secondhand)

Last year I read the previous book,

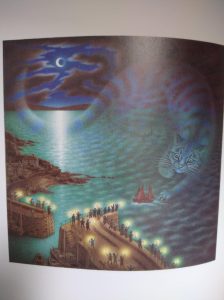

Last year I read the previous book,  The Mousehole Cat by Antonia Barber; illus. Nicola Bayley (1990) – The town of Mousehole in Cornwall (the far southwest of England) relies on fishing. Old Tom brings some of his catch home every day for his cat Mowzer; they have a household menu with a different fishy dish for each day of the week. One winter a storm prevents the fishing boats from leaving the cove and the people – and kitties – start to starve. Tom decides he’ll go out in his boat anyway, and Mowzer goes along to sing and tame the Great Storm-Cat. This story of bravery was ever so cute, words and pictures both, and I especially liked how Mowzer considers Tom her pet. (Free from a neighbour)

The Mousehole Cat by Antonia Barber; illus. Nicola Bayley (1990) – The town of Mousehole in Cornwall (the far southwest of England) relies on fishing. Old Tom brings some of his catch home every day for his cat Mowzer; they have a household menu with a different fishy dish for each day of the week. One winter a storm prevents the fishing boats from leaving the cove and the people – and kitties – start to starve. Tom decides he’ll go out in his boat anyway, and Mowzer goes along to sing and tame the Great Storm-Cat. This story of bravery was ever so cute, words and pictures both, and I especially liked how Mowzer considers Tom her pet. (Free from a neighbour)

I’ve read all but one of Bechdel’s works now.

I’ve read all but one of Bechdel’s works now.

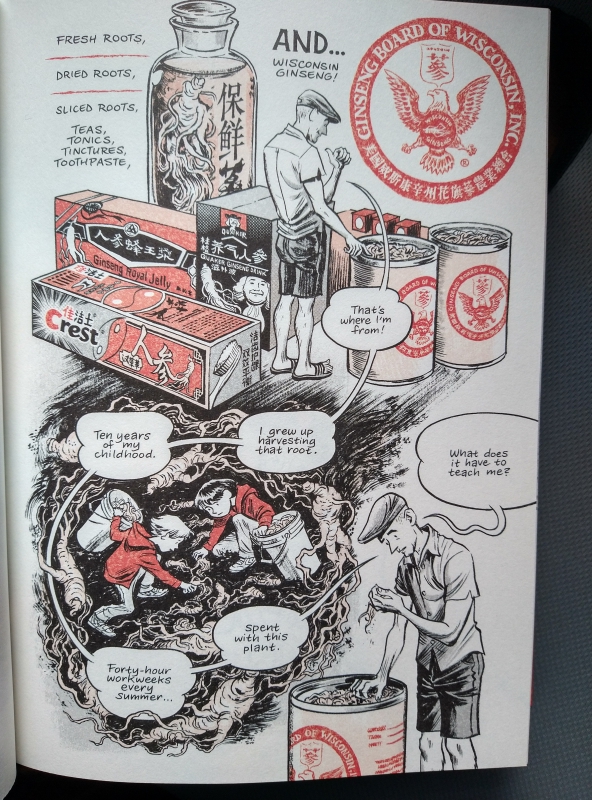

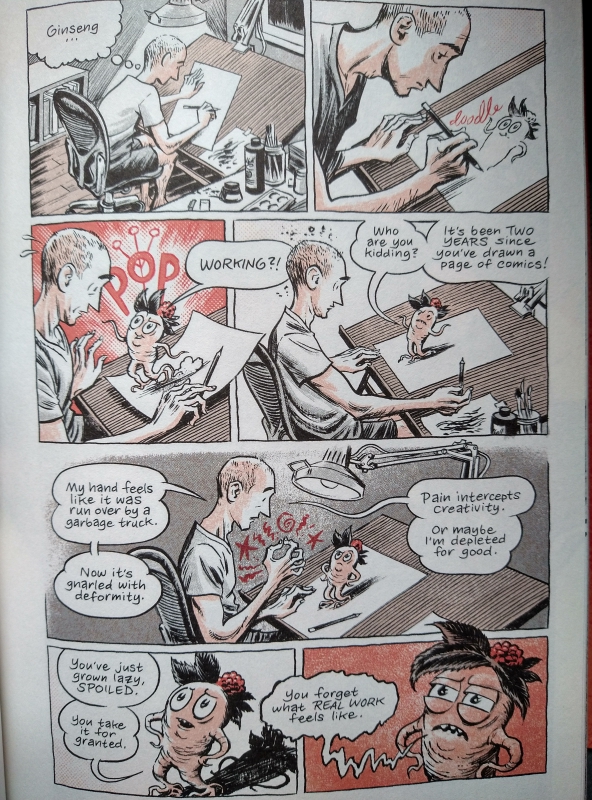

Nearly a decade ago, I reviewed Peter Kuper’s

Nearly a decade ago, I reviewed Peter Kuper’s

I’d read several of Thompson’s works and especially enjoyed his previous graphic memoir,

I’d read several of Thompson’s works and especially enjoyed his previous graphic memoir,

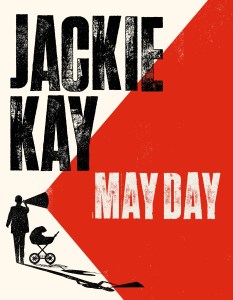

May Day is a traditional celebration for the first day of May, but it’s also a distress signal – as the megaphone and stark font on the cover reflect. Aptly, there are joyful verses as well as calls to arms here. Kay devotes poems to several of her role models, such as Harry Belafonte, Paul Robeson, Peggy Seeger and Nina Simone. But the real heroes of the book are her late parents, who were very politically active, standing up for workers’ rights and socialist values. Kay followed in their footsteps as a staunch attendee of protests. Her mother’s death during the Covid pandemic looms large. There is a touching triptych set on Mother’s Day in three consecutive years; even though her mum is gone for the last two, Kay still talks to her. Certain birds and songs will always remind her of her mum, and “Grief as Protest” links past and future. The bereavement theme resonated with me, but much of the rest made no mark (especially not the poems in dialect) and I don’t find much to admire poetically. I love Kay’s memoir, Red Dust Road, which has been among our most popular book club reads so far, but I’ve not particularly warmed to her poetry despite having read four collections now.

May Day is a traditional celebration for the first day of May, but it’s also a distress signal – as the megaphone and stark font on the cover reflect. Aptly, there are joyful verses as well as calls to arms here. Kay devotes poems to several of her role models, such as Harry Belafonte, Paul Robeson, Peggy Seeger and Nina Simone. But the real heroes of the book are her late parents, who were very politically active, standing up for workers’ rights and socialist values. Kay followed in their footsteps as a staunch attendee of protests. Her mother’s death during the Covid pandemic looms large. There is a touching triptych set on Mother’s Day in three consecutive years; even though her mum is gone for the last two, Kay still talks to her. Certain birds and songs will always remind her of her mum, and “Grief as Protest” links past and future. The bereavement theme resonated with me, but much of the rest made no mark (especially not the poems in dialect) and I don’t find much to admire poetically. I love Kay’s memoir, Red Dust Road, which has been among our most popular book club reads so far, but I’ve not particularly warmed to her poetry despite having read four collections now. I’d not read Morpurgo before. He’s known primarily as a children’s author; if you’ve heard of one of his works, it will likely be War Horse, which became a play and then a film. This is a small hardback, scarcely 150 pages and with not many words to a page, plus woodcut illustrations interspersed. As revered English nature authors such as John Lewis-Stempel and Richard Mabey have also done, he depicts a typical season through a diary of several months of life on his land. For nearly 50 years, his Devon farm has hosted the Farms for City Children charity he founded. He believes urban living cuts people off from the rhythm of the seasons and from nature generally; “For so many reasons, for our wellbeing, for the planet, we need to revive that connection.” Now in his eighties, he lives with his wife in a small cottage and leaves much of the day-to-day work like lambing to others. But he still loves observing farm tasks and spotting wildlife (notably, an otter and a kingfisher) on his walks. This is a pleasant but inconsequential book. I most appreciated how it captures the feeling of seasonal anticipation – wondering when the weather will turn, when that first swallow will return.

I’d not read Morpurgo before. He’s known primarily as a children’s author; if you’ve heard of one of his works, it will likely be War Horse, which became a play and then a film. This is a small hardback, scarcely 150 pages and with not many words to a page, plus woodcut illustrations interspersed. As revered English nature authors such as John Lewis-Stempel and Richard Mabey have also done, he depicts a typical season through a diary of several months of life on his land. For nearly 50 years, his Devon farm has hosted the Farms for City Children charity he founded. He believes urban living cuts people off from the rhythm of the seasons and from nature generally; “For so many reasons, for our wellbeing, for the planet, we need to revive that connection.” Now in his eighties, he lives with his wife in a small cottage and leaves much of the day-to-day work like lambing to others. But he still loves observing farm tasks and spotting wildlife (notably, an otter and a kingfisher) on his walks. This is a pleasant but inconsequential book. I most appreciated how it captures the feeling of seasonal anticipation – wondering when the weather will turn, when that first swallow will return. This 400+-page tome has an impressive scope. Like Mark Cocker does in

This 400+-page tome has an impressive scope. Like Mark Cocker does in