Reviewing Two Books by Cancelled Authors

I don’t have anything especially insightful to say about these authors’ reasons for being cancelled, although in my review of the Clanchy I’ve noted the textual examples that have been cited as problematic. Alexie is among the legion of male public figures to have been accused of sexual misconduct in recent years. I’m not saying those aren’t serious allegations, but as Claire Dederer wrestled with in Monsters, our judgement of a person can be separate from our response to their work. So that’s the good news: I thought these were both fantastic books. They share a theme of education.

The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian by Sherman Alexie (illus. Ellen Forney) (2007)

Alexie is to be lauded for his contributions to the flourishing of both Indigenous literature and YA literature. This was my first of his books and I don’t know a thing about him or the rest of his work. But I feel like this must have groundbreaking for its time (or maybe a throwback to Adrian Mole et al.), and I suspect it’s more than a little autobiographical.

Alexie is to be lauded for his contributions to the flourishing of both Indigenous literature and YA literature. This was my first of his books and I don’t know a thing about him or the rest of his work. But I feel like this must have groundbreaking for its time (or maybe a throwback to Adrian Mole et al.), and I suspect it’s more than a little autobiographical.

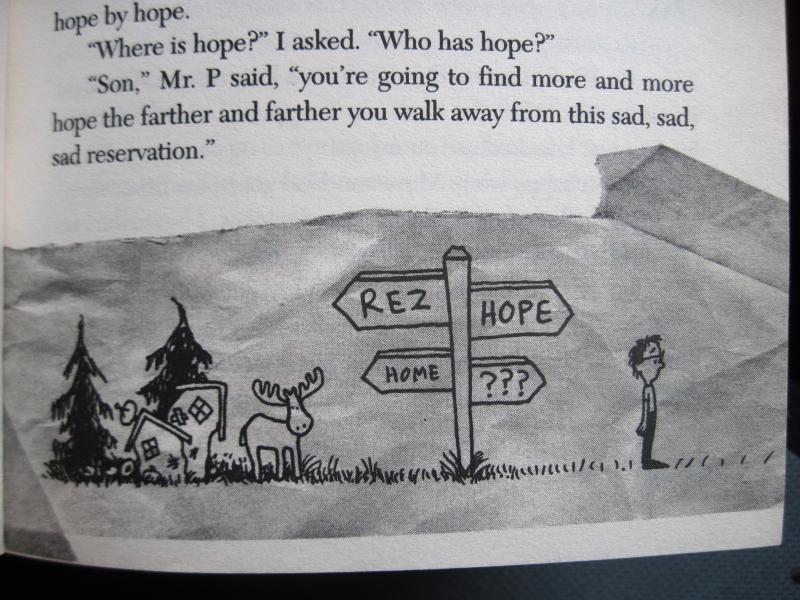

It reads exactly like a horny 14-year-old boy’s diary, but “Junior” (Arnold Spirit, Jr.) is also self-deprecating and sweetly vulnerable; Alexie’s tone is spot on. Junior has had a tough life on a Spokane reservation in Washington, being bullied for his poor eyesight and speech impediments that resulted from brain damage at birth and ongoing seizures. Poverty, alcoholism, casinos: they don’t feel like clichés of Indian reservations here because Alexie writes from experience and presents them matter-of-factly. Junior’s parents never got to pursue their dreams and his sister has run away to Montana, but he has a chance to change the trajectory. A rez teacher says his only hope for a bright future is to transfer to the elite high school in Reardan. So he does, even though it often requires hitch-hiking or walking miles.

Junior soon becomes adept at code-switching: “Traveling between Reardan and Wellpinit, between the little white town and the reservation, I always felt like a stranger. I was half Indian in one place and half white in the other.” He gets a white girlfriend, Penelope, but has to work hard to conceal how impoverished he is. His best friend, Rowdy, is furious with him for abandoning his people. That resentment builds all the way to a climactic basketball match between Reardan and Wellpinit that also functions as a symbolic battle between the parts of Junior’s identity. Along the way, there are multiple tragic deaths in which alcohol, inevitably, plays a role. “I’m fourteen years old and I’ve been to forty-two funerals,” he confides. “Jeez, what a sucky life. … I kept trying to find the little pieces of joy in my life. That’s the only way I managed to make it through all of that death and change.”

One of those joys, for him, is cartooning. Describing his cartoons to his new white friend, Gordy, he says, “I use them to understand the world.”

Forney’s black-and-white illustrations make the cartoons look like found objects – creased scraps of notebook paper sellotaped into a diary. This isn’t a graphic novel, but most of the short chapters include several illustrations. There’s a casual intimacy to the whole book that feels absolutely authentic. Bridging the particular and universal, it’s a heartfelt gem, and not just for teens. (University library) ![]()

Some Kids I Taught and What They Taught Me by Kate Clanchy (2019)

If your Twitter sphere and mine overlap, you may remember the controversy over the racialized descriptions in this Orwell Prize-winning memoir of 30 years of teaching – and the fact that, rather than issuing a humbled apology, Clanchy, at least initially, doubled down and refuted all objections, even when they came from BIPOC. It wasn’t a good look. Nor was it the first time I’ve found Clanchy to be prickly. (She is what, in another time, might have been called a formidable woman.) Anyway, I waited a few years for the furore to die down before trying this for myself.

I know vanishingly little about the British education system because I don’t have children and only experienced uni here at a distance, through my junior year abroad. So there may be class-based nuances I missed – for instance, in the chapter about selecting a school for her oldest son and comparing it with the underprivileged Essex school where she taught. But it’s clear that a lot of her students posed serious challenges. Many were refugees or immigrants, and she worked for a time on an “Inclusion Unit,” which seems to be more in the business of exclusion in that it’s for students who have been removed from regular classrooms. They came from bad family situations and were more likely to end up in prison or pregnant. To get any of them to connect with Shakespeare, or write their own poetry, was a minor miracle.

Clanchy is also a poet and novelist – I’ve read one of her novels, and her Selected Poems – and did much to encourage her students to develop a voice and the confidence to have their work published (she’s produced anthologies of student work). In many cases, she gave them strategies for giving literary shape to traumatic memories. The book’s engaging vignettes have all had the identifying details removed, and are collected under thematic headings that address the second part of the title: “About Love, Sex, and the Limits of Embarrassment” and “About Nations, Papers, and Where We Belong” are two example chapters. She doesn’t avoid contentious topics, either: the hijab, religion, mental illness and so on.

You get the feeling that she was a friend and mentor to her students, not just their teacher, and that they could talk to her about anything and rely on her support. Watching them grow in self-expression is heart-warming; we come to care for these young people, too, because of how sincerely they have been created from amalgams. Indeed, Clanchy writes in the introduction that “I have included nobody, teacher or pupil, about whom I could not write with love.”

And that is, I think, why she was so hurt and disbelieving when people pointed out racism in her characterization:

I was baffled when a boy with jet-black hair and eyes and a fine Ashkenazi nose named David Marks refused any Jewish heritage

her furry eyebrows, her slanting, sparking black eyes, her general, Mongolian ferocity. [but she’s Afghan??]

(of girls in hijabs) I never saw their (Asian/silky/curly?) hair in eight years.

They’re a funny pair: Izzat so small and square and Afghan with his big nose and premature moustache; Mo so rounded and mellow and Pakistani with his long-lashed eyes and soft glossy hair.

There are a few other ill-advised passages. She admits she can’t tell the difference between Kenyan and Somali faces; she ponders whether being a Scot in England gave her some taste of the prejudice refugees experience. And there’s this passage about sexuality:

Are we all ‘fluid’ now? Perhaps. It is commonplace to proclaim oneself transsexual. And to actually be gay, especially if you are as pretty as Kristen Stewart, is positively fashionable. A couple of kids have even changed gender, a decision … deliciously of the moment

My take: Clanchy wanted to craft affectionate pen portraits that celebrated children’s uniqueness, but had to make them anonymous, so resorted to generalizations. Doing this on a country or ethnicity basis was the mistake. Journalistic realism doesn’t require a focus on appearances (I would hope that, if I were ever profiled, someone could find more interesting things to say about me than that I am short and have a large nose). She could have just introduced the students with ‘facts,’ e.g., “Shakila, from Afghanistan, wore a hijab and was feisty and outspoken.” Note to self: white people can be clueless, and we need to listen and learn. The book was reissued in 2022 by independent publisher Swift Press, with offending passages removed (see here for more info). I’d be keen to see the result and hope that the book will find more readers because, truly, it is lovely. (Little Free Library) ![]()

Miscellaneous #ReadIndies Reviews: Mostly Poetry + Brown, Sands

Catching up on a few final #ReadIndies contributions in early March! Short responses to some indie reading I did from my shelves over the course of last month.

Bloodaxe Books:

Parables & Faxes by Gwyneth Lewis (1995)

I was surprised to discover this was actually my fourth book by Lewis, a bilingual Welsh author: two memoirs, one of depression and one about marriage; and now two poetry collections. The table of contents suggest there are only 16 poems in the book, but most of the titles are actually headings for sections of anywhere between 6 and 16 separate poems. She ranges widely at home and abroad, as in “Welsh Espionage” and the “Illinois Idylls.” “I shall taste the tang / of travel on the atlas of my tongue,” Lewis writes, an example of her alliteration and sibilance. She’s also big on slant and internal rhymes – less so on end rhymes, though there are some. Medieval history and theology loom large, with the Annunciation featuring more than once. I couldn’t tell you now what that many of the poems are about, but Lewis’s telling is always memorable.

I was surprised to discover this was actually my fourth book by Lewis, a bilingual Welsh author: two memoirs, one of depression and one about marriage; and now two poetry collections. The table of contents suggest there are only 16 poems in the book, but most of the titles are actually headings for sections of anywhere between 6 and 16 separate poems. She ranges widely at home and abroad, as in “Welsh Espionage” and the “Illinois Idylls.” “I shall taste the tang / of travel on the atlas of my tongue,” Lewis writes, an example of her alliteration and sibilance. She’s also big on slant and internal rhymes – less so on end rhymes, though there are some. Medieval history and theology loom large, with the Annunciation featuring more than once. I couldn’t tell you now what that many of the poems are about, but Lewis’s telling is always memorable.

Sample lines:

For the one

who said yes,

how many

said no?

…

But those who said no

for ever knew

they were damned

to the daily

as they’d disallowed

reality’s madness,

its astonishment.

(from “The ‘No’ Madonnas,” part of “Parables & Faxes”)

(Secondhand purchase – Westwood Books, Sedbergh)

&

Fields Away by Sarah Wardle (2003)

Wardle’s was a new name for me. I saw two of her collections at once and bought this one as it was signed and the themes sounded more interesting to me. It was her first book, written after inpatient treatment for schizophrenia. Many of the poems turn on the contrast between city (London Underground) and countryside (fields and hedgerows). Religion, philosophy, and Greek mythology are common points of reference. End rhymes can be overdone here, and I found a few of the poems unsubtle (“Hubris” re: colonizers and “How to Be Bad” about daily acts of selfishness vs. charity). However, there are enough lovely ones to compensate: “Flight,” “Word Tasting” (mimicking a wine tasting), “After Blake” (reworking “Jerusalem” with “And will chainsaws in modern times / roar among England’s forests green?”), “Translations” and “Word Hill.”

Wardle’s was a new name for me. I saw two of her collections at once and bought this one as it was signed and the themes sounded more interesting to me. It was her first book, written after inpatient treatment for schizophrenia. Many of the poems turn on the contrast between city (London Underground) and countryside (fields and hedgerows). Religion, philosophy, and Greek mythology are common points of reference. End rhymes can be overdone here, and I found a few of the poems unsubtle (“Hubris” re: colonizers and “How to Be Bad” about daily acts of selfishness vs. charity). However, there are enough lovely ones to compensate: “Flight,” “Word Tasting” (mimicking a wine tasting), “After Blake” (reworking “Jerusalem” with “And will chainsaws in modern times / roar among England’s forests green?”), “Translations” and “Word Hill.”

Favourite lines:

(oh, but the last word is cringe!)

Catkin days and hedgerow hours

fleet like shafts of chapel sun.

Childhood in a cobwebbed bower

guards a treasure chest of fun.

(from “Age of Awareness”)

(Secondhand purchase – Carlisle charity shop)

Carcanet Press:

Tripping Over Clouds by Lucy Burnett (2019)

The title is a setup for the often surrealist approach, but where another Carcanet poet, Caroline Bird, is warm and funny with her absurdism, Burnett is just … weird. Like, I’d get two stanzas into a poem and have no idea what was going on or what she was trying to say because of the incomplete phrases and non-standard punctuation. Still, this is a long enough collection that there are a good number of standouts about nature and relationships, and alliteration and paradoxes are used to good effect. I liked the wordplay in “The flight of the guillemet” and the off-beat love poem “Beer for two in Brockler Park, Berlin.” The noteworthy Part III is composed of 34 ekphrastic poems, each responding to a different work of (usually modern) art.

The title is a setup for the often surrealist approach, but where another Carcanet poet, Caroline Bird, is warm and funny with her absurdism, Burnett is just … weird. Like, I’d get two stanzas into a poem and have no idea what was going on or what she was trying to say because of the incomplete phrases and non-standard punctuation. Still, this is a long enough collection that there are a good number of standouts about nature and relationships, and alliteration and paradoxes are used to good effect. I liked the wordplay in “The flight of the guillemet” and the off-beat love poem “Beer for two in Brockler Park, Berlin.” The noteworthy Part III is composed of 34 ekphrastic poems, each responding to a different work of (usually modern) art.

Favourite lines:

This is a place of uncalled-for space

and by the grace of the big sky,

and the serrated under-silhouette of Skye,

an invitation to the sea unfolds

to come and dine with mountain.

(from “Big Sands”)

(New (bargain) purchase – Waterstones website)

&

The Met Office Advises Caution by Rebecca Watts (2016)

The problem with buying a book mostly for the title is that often the contents don’t live up to it. (Some of my favourite ever titles – An Arsonist’s Guide to Writers’ Homes in New England, The Voluptuous Delights of Peanut Butter and Jam – were of books I couldn’t get through). There are a lot of nature poems here, which typically would be enough to get me on board, but few of them stood out to me. Trees, bats, a dead hare on the road; maps, Oxford scenes, Christmas approaching. All nice enough; maybe it’s just that the poems don’t seem to form a cohesive whole. Easy to say why I love or hate a poet’s style; harder to explain indifference.

The problem with buying a book mostly for the title is that often the contents don’t live up to it. (Some of my favourite ever titles – An Arsonist’s Guide to Writers’ Homes in New England, The Voluptuous Delights of Peanut Butter and Jam – were of books I couldn’t get through). There are a lot of nature poems here, which typically would be enough to get me on board, but few of them stood out to me. Trees, bats, a dead hare on the road; maps, Oxford scenes, Christmas approaching. All nice enough; maybe it’s just that the poems don’t seem to form a cohesive whole. Easy to say why I love or hate a poet’s style; harder to explain indifference.

Sample lines:

Branches lash out; old trees lie down and don’t get up.

A wheelie bin crosses the road without looking,

lands flat on its face on the other side, spilling its knowledge.

(from the title poem)

(New (bargain) purchase – Amazon with Christmas voucher)

Faber:

Places I’ve Taken My Body by Molly McCully Brown (2020)

The title signals right away how these linked autobiographical essays split the ‘I’ from the body – Brown resents the fact that disability limits her experience. Oxygen deprivation at their premature birth led to her twin sister’s death and left her with cerebral palsy severe enough that she generally uses a wheelchair. In Bologna for a travel fellowship, she writes, “There are so many places that I want to be, but I can’t take my body anywhere. But I must take my body everywhere.” A medieval city is particularly unfriendly to those with mobility challenges, but chronic pain and others’ misconceptions (e.g. she overheard a guy on her college campus lamenting that she’d die a virgin) follow her everywhere.

The title signals right away how these linked autobiographical essays split the ‘I’ from the body – Brown resents the fact that disability limits her experience. Oxygen deprivation at their premature birth led to her twin sister’s death and left her with cerebral palsy severe enough that she generally uses a wheelchair. In Bologna for a travel fellowship, she writes, “There are so many places that I want to be, but I can’t take my body anywhere. But I must take my body everywhere.” A medieval city is particularly unfriendly to those with mobility challenges, but chronic pain and others’ misconceptions (e.g. she overheard a guy on her college campus lamenting that she’d die a virgin) follow her everywhere.

A poet, Brown earned minor fame for her first collection, which was about historical policies of enforced sterilization for the disabled and mentally ill in her home state of Virginia. She is also a Catholic convert. I appreciated her exploration of poetry and faith as ways of knowing: “both … a matter of attending to the world: of slowing my pace, and focusing my gaze, and quieting my impatient, indignant, protesting heart long enough for the hard shell of the ordinary to break open and reveal the stranger, subtler singing underneath.” This is part of a terrific run of three pieces, the others about sex as a disabled person and the odious conservatism of the founders of Liberty University. Also notable: “Fragments, Never Sent,” letters to her twin; and “Frankenstein Abroad,” about rereading this novel of ostracism at its 200th anniversary. (Secondhand purchase – Amazon)

New River Books:

The Hedgehog Diaries: A Story of Faith, Hope and Bristle by Sarah Sands (2023)

Reasons for reading: 1) I’d enjoyed Sands’s The Interior Silence and 2) Who can resist a book about hedgehogs? She covers a brief slice of 2021–22 when her aged father was dying in a care home. Having found an ill hedgehog in her garden and taken it to a local sanctuary, she developed an interest in the plight of hedgehogs. In surveys they’re the UK’s favourite mammal, but it’s been years since I saw one alive. Sands brings an amateur’s enthusiasm to her research into hedgehogs’ place in literature, philosophy and science. She visits rescue centres, meets activists in Oxfordshire and Shropshire who have made hedgehog welfare a local passion, and travels to Uist to see where hedgehogs were culled in 2004 to protect ground-nesting birds’ eggs. The idea is to link personal brushes with death with wider threats of extinction. Unfortunately, Sands’s lack of expertise is evident. This was well-meaning, but inconsequential and verging on twee. (Christmas gift from my wishlist)

Reasons for reading: 1) I’d enjoyed Sands’s The Interior Silence and 2) Who can resist a book about hedgehogs? She covers a brief slice of 2021–22 when her aged father was dying in a care home. Having found an ill hedgehog in her garden and taken it to a local sanctuary, she developed an interest in the plight of hedgehogs. In surveys they’re the UK’s favourite mammal, but it’s been years since I saw one alive. Sands brings an amateur’s enthusiasm to her research into hedgehogs’ place in literature, philosophy and science. She visits rescue centres, meets activists in Oxfordshire and Shropshire who have made hedgehog welfare a local passion, and travels to Uist to see where hedgehogs were culled in 2004 to protect ground-nesting birds’ eggs. The idea is to link personal brushes with death with wider threats of extinction. Unfortunately, Sands’s lack of expertise is evident. This was well-meaning, but inconsequential and verging on twee. (Christmas gift from my wishlist)

A Bookshop of One’s Own by Jane Cholmeley (Blog Tour)

Silver Moon, one of the Charing Cross Road bookshops, was a London institution from 1984 until its closure in 2001. “Feminism and business are strange bedfellows,” Jane Cholmeley soon realised, and this book is her record of the challenges of combining the two. On the spectrum of personal to political, this is much more manifesto than memoir. She dispenses with her own story (vicar’s tomboy daughter, boarding school, observing racism on a year abroad in Virginia, secretarial and publishing jobs, meeting her partner) via a 10-page “Who Am I?” opening chapter. However, snippets of autobiography do enter into the book later on; in one of my favourite short chapters, “Coming Out,” Cholmeley recalls finally telling her mother that she was a lesbian after she and Sue had been together nearly a decade.

The mid-1980s context plays a major role: Thatcherite policies (Section 28 outlawing the “promotion of homosexuality”), negotiations with the Greater London Council, and trying to share the landscape with other feminist bookshops like Sisterwrite and Virago. Although there were some low-key rivalries and mean-spirited vandalism, a spirit of camaraderie generally prevailed. Cholmeley estimates that about 30% of the shop’s customers were men, but the focus here was always on women. The events programme featured talks by an amazing who’s-who of women authors, Cholmeley was part of the initial roundtable discussions in 1992 that launched the Orange Prize for Fiction (now the Women’s Prize), and the café was designated a members’ club so that it could legally be a women-only space.

I’ve always loved reading about what goes on behind the scenes in bookshops (The Diary of a Bookseller, Diary of a Tuscan Bookshop, The Sentence, The Education of Harriet Hatfield, The Little Bookstore of Big Stone Gap, and so on), and Cholmeley ably conveys the buzzing girl-power atmosphere of hers. There is a fun sense of humour, too: “Dyke and Doughnut” was a potential shop name, and a letter to one potential business partner read, “you already eat lentils, and ride a bicycle, so your standard of living hasn’t got much further to fall, we happen to like you an awful lot, and think we could all work together in relative harmony”.

However, the book does not have a narrative per se; the “A Day in the Life of… (1996)” chapter comes closest to what those hoping for a bookseller memoir might be expecting, in that it actually recreates scenes and dialogue. The rest is a thematic chronicle, complete with lists, sales figures, profitability charts, and excerpted documents, and I often got lost in the detail. The fact that this gives the comprehensive history of one establishment makes it a nostalgic yearbook that will appeal most to readers who have a head for business, were dedicated Silver Moon customers, and/or hold a particular personal or academic interest in the politics of the time and the development of the feminist and LGBT movements.

With thanks to Random Things Tours and Mudlark for the free copy for review.

Buy A Bookshop of One’s Own from Bookshop.org [affiliate link]

I was happy to be part of the blog tour for the release of this book. See below for details of where other reviews have appeared or will be appearing soon.

Three “Love” or “Heart” Books for Valentine’s Day: Ephron, Lischer and Nin

Every year I say I’m really not a Valentine’s Day person and yet put together a themed post featuring books that have “Love” or a similar word in the title. This is the eighth year in a row, in fact (after 2017, 2018, 2019, 2020, 2021, 2022, and 2023)! Today I’m looking at two classic novellas, one of them a reread and the other my first taste of a writer I’d expected more from; and a wrenching, theologically oriented bereavement memoir.

Heartburn by Nora Ephron (1983)

I’d already pulled this out for my planned reread of books published in my birth year, so it’s pleasing that it can do double duty here. I can’t say it better than my original 2013 review:

The funniest book you’ll ever read about heartbreak and betrayal, this is full of wry observations about the compromises we make to marry – and then stay married to – people who are very different from us. Ephron readily admitted that her novel is more than a little autobiographical: it’s based on the breakdown of her second marriage to investigative journalist Carl Bernstein (All the President’s Men), who had an affair with a ludicrously tall woman – one element she transferred directly into Heartburn.

Ephron’s fictional counterpart is Rachel Samstad, a New Yorker who writes cookbooks or, rather, memoirs with recipes – before that genre really took off. Seven months pregnant with her second child, she has just learned that her second husband is having an affair. What follows is her uproarious memories of life, love and failed marriages. Indeed, as Ephron reflected in a 2004 introduction, “One of the things I’m proudest of is that I managed to convert an event that seemed to me hideously tragic at the time to a comedy – and if that’s not fiction, I don’t know what is.”

As one might expect from a screenwriter, there is a cinematic – that is, vivid but not-quite-believable – quality to some of the moments: the armed robbery of Rachel’s therapy group, her accidentally flinging an onion into the audience during a cooking demonstration, her triumphant throw of a key lime pie into her husband’s face in the final scene. And yet Ephron was again drawing on experience: a friend’s therapy group was robbed at gunpoint, and she’d always filed the experience away in a mental drawer marked “Use This Someday” – “My mother taught me many things when I was growing up, but the main thing I learned from her is that everything is copy.” This is one of celebrity chef Nigella Lawson’s favorite books ever, for its mixture of recipes and rue, comfort food and folly. It’s a quick read, but a substantial feast for the emotions.

Sometimes I wonder why I bother when I can’t improve on reviews I wrote over a decade ago (see also another upcoming reread). What I would add now, without disputing any of the above, is that there’s more bitterness to the tone than I’d recalled, even though Ephron does, yes, play it for laughs. But also, some of the humour hasn’t aged well, especially where based on race/culture or sexuality. I’d forgotten that Rachel’s husband isn’t the only cheater here; pretty much every couple mentioned is currently working through the aftermath of an affair or has survived one in the past. In one of these, the wife who left for a woman is described not as a lesbian but by another word, each time, which felt unkind rather than funny.

Sometimes I wonder why I bother when I can’t improve on reviews I wrote over a decade ago (see also another upcoming reread). What I would add now, without disputing any of the above, is that there’s more bitterness to the tone than I’d recalled, even though Ephron does, yes, play it for laughs. But also, some of the humour hasn’t aged well, especially where based on race/culture or sexuality. I’d forgotten that Rachel’s husband isn’t the only cheater here; pretty much every couple mentioned is currently working through the aftermath of an affair or has survived one in the past. In one of these, the wife who left for a woman is described not as a lesbian but by another word, each time, which felt unkind rather than funny.

Still, the dialogue, the scenes, the snarky self-portrayal: it all pops. This was autofiction before that was a thing, but anyone working in any genre could learn how to write readable content by studying Ephron. “‘I don’t have to make everything into a joke,’ I said. ‘I have to make everything into a story.’ … I think you often have that sense when you write – that if you can spot something in yourself and set it down on paper, you’re free of it. And you’re not, of course; you’ve just managed to set it down on paper, that’s all.” (Little Free Library)

My original rating (2013):

My rating now:

Stations of the Heart: Parting with a Son by Richard Lischer (2013)

“What we had taken to be a temporary unpleasantness had now burrowed deep into the family pulp and was gnawing us from the inside out.” Like all life writing, the bereavement memoir has two tasks: to bear witness and to make meaning. From a distance that just happens to be Mary Karr’s prescribed seven years, Lischer opens by looking back on the day when his 33-year-old son Adam called to tell him that his melanoma, successfully treated the year before, was back. Tests revealed that the cancer’s metastases were everywhere, including in his brain, and were “innumerable,” a word that haunted Lischer and his wife, their daughter, and Adam’s wife, who was pregnant with their first child.

The next few months were a Calvary of sorts, and Lischer, an emeritus professor at Duke Divinity School, draws deliberate parallels with the biblical and liturgical preparations for Good Friday that feel appropriate for this Ash Wednesday. Lischer had no problem with Adam’s late-life conversion from Protestantism to Catholicism, whose rites he followed with great piety in his final summer. He traces Adam and Jenny’s daily routines as well as his own helpless attendance at hospital appointments. Doped up on painkillers, Adam attended one last Father’s Day baseball game with him; one last Fourth of July picnic. Everyone so desperately wanted him to keep going long enough to meet his baby girl. To think that she is now a young woman and has opened all the presents Adam bought to leave behind for her first 18 birthdays.

The next few months were a Calvary of sorts, and Lischer, an emeritus professor at Duke Divinity School, draws deliberate parallels with the biblical and liturgical preparations for Good Friday that feel appropriate for this Ash Wednesday. Lischer had no problem with Adam’s late-life conversion from Protestantism to Catholicism, whose rites he followed with great piety in his final summer. He traces Adam and Jenny’s daily routines as well as his own helpless attendance at hospital appointments. Doped up on painkillers, Adam attended one last Father’s Day baseball game with him; one last Fourth of July picnic. Everyone so desperately wanted him to keep going long enough to meet his baby girl. To think that she is now a young woman and has opened all the presents Adam bought to leave behind for her first 18 birthdays.

The facts of the story are heartbreaking enough, but Lischer’s prose is a perfect match: stately, resolute and weighted with spiritual allusion, yet never morose. He approaches the documenting of his son’s too-short life with a sense of sacred duty: “I have acquired a new responsibility: I have become the interpreter of his death. God, I must do a better job. … I kissed his head and thanked him for being my son. I promised him then that his death would not ruin my life.” This memoir brought back so much about my brother-in-law’s death from brain cancer in 2015, from the “TEAM [ADAM/GARNET]” T-shirts to Adam’s sister’s remark, “I never dreamed this would be our family’s story.” We’re not alone. (Remainder book from the Bowie, Maryland Dollar Tree)

A Spy in the House of Love by Anaïs Nin (1954)

I’d heard Nin spoken of in the same breath as D.H. Lawrence, so thought I might similarly appreciate her because of, or despite, comically overblown symbolism around sex. I think I was also expecting something more titillating? (I guess I had this confused for Delta of Venus, her only work that would be shelved in an Erotica section.) Many have tried to make a feminist case for this novella about Sabina, an early liberated woman in New York City who has extramarital sex with four other men who appeal to her for various not particularly good reasons (the traumatized soldier whom she comforts like a mother; the exotic African drummer – “Sabina did not feel guilty for drinking of the tropics through Mambo’s body”). She herself states, “I want to trespass boundaries, erase all identifications, anything which fixes one permanently into one mould, one place without hope of change.” The most interesting aspect of the book was Sabina’s questioning of whether she inherited her promiscuity from her father (it’s tempting to read this autobiographically as Nin’s own father left the family for another woman, a foundational wound in her life).

I’d heard Nin spoken of in the same breath as D.H. Lawrence, so thought I might similarly appreciate her because of, or despite, comically overblown symbolism around sex. I think I was also expecting something more titillating? (I guess I had this confused for Delta of Venus, her only work that would be shelved in an Erotica section.) Many have tried to make a feminist case for this novella about Sabina, an early liberated woman in New York City who has extramarital sex with four other men who appeal to her for various not particularly good reasons (the traumatized soldier whom she comforts like a mother; the exotic African drummer – “Sabina did not feel guilty for drinking of the tropics through Mambo’s body”). She herself states, “I want to trespass boundaries, erase all identifications, anything which fixes one permanently into one mould, one place without hope of change.” The most interesting aspect of the book was Sabina’s questioning of whether she inherited her promiscuity from her father (it’s tempting to read this autobiographically as Nin’s own father left the family for another woman, a foundational wound in her life).

Come on, though, “fecundated,” “fecundation” … who could take such vocabulary seriously? Or this sex writing (snort!): “only one ritual, a joyous, joyous, joyous impaling of woman on a man’s sensual mast.” I charge you to use the term “sensual mast” wherever possible in the future. (Secondhand – Oxfam, Newbury)

But hey, check out my score for the Faber Valentine’s quiz!

Review: The Tidal Year by Freya Bromley (2023)

The Nero Book Awards category winners will be announced on Tuesday. I haven’t had a chance to read as many of the nominees as I would like, but I’m catching up on one that I’ve wanted to read ever since I first heard about it early last year. Even though Stephen Collins sums up about my feelings about coldwater swimming well in this cartoon –

– I was drawn to The Tidal Year for several reasons. First off, I’ll read just about any bereavement memoir going. Second, I love following along on a year challenge. Third, even though I haven’t been much of a swimmer since childhood, I appreciate how outdoor swimming combines observation of nature and the seasons with achievable bodily exploits; you don’t have to be an exercise nut or undergo lots of training to get into it. There was a spate of swimming memoirs back in 2017, including Jessica J. Lee’s superb Turning and Ruth Fitzmaurice’s I Found My Tribe. Headlines often tout the physical benefits of coldwater swimming, but it’s the emotional benefits that Bromley emphasizes in this record of facing grief and opening up to love.

Bromley was the middle of five children but her boisterous family’s dynamic went out of kilter when her younger brother Tom was diagnosed with bone cancer and died at age 19. Suddenly she could hardly talk to her mother, let alone to Tom’s twin, Emma. Isolated in London, where she worked in music journalism, she roped her friend Miri into wild swimming excursions and threw herself into Internet dating. She and Miri concocted a plan to swim in all of Britain’s mainland tidal pools (saltwater enclosed by manmade elements) in a year; she started seeing Jem, a free-spirited documentary filmmaker – but also Flip, a Black actor she met when he came to buy her neighbour’s antique chairs; he nicknamed her “Poet” and encouraged her in her writing.

Each short chapter is identified by a place name and its geographical coordinates. Most often, these correspond to a swimming destination, but they can also be clues to interludes or flashbacks, whether set in London (“Jem’s Skylight”), on the last night she spent by Tom’s hospital bedside, or at the Brecon Beacons home her parents moved to after Tom’s death. A lot of the tidal pools are in Devon and Cornwall, but she and Miri also make expeditions to Scotland and Wales and elsewhere along the south coast.

At a certain point Bromley realizes that they aren’t going to hit every single pool before the year is over, but the goal starts to matter less than the slow internal transformation that’s taking place. “Swimming had been a way for me to rediscover my body as a place of power, play and movement.” We see the gradual shifts: she’s more able to talk about Tom, she commits to her writing through a Cambridge course, she’s a supportive big sister to Emma, and she breaks it off with one of the boyfriends.

I had to suppress my judgemental side here. I know monogamy is not a universal value, especially among a younger generation, and Bromley does acknowledge that she was behaving badly in stringing two partners along – grief leads people to make decisions they might not normally. The other niggle for this pedantic proofreader was the non-standard way of introducing dialogue. Bromley chose to put all dialogue in italics – fine with me – but doesn’t consistently bracket phrases with “I said” or “she asked.” Usually it’s clear enough, but sometimes the interruption of speech with gesture is downright maddening, e.g., “There’s this, I blew on the tea, well inside me” and “It’s magic isn’t it, Miri rolled down her window”.

But I was (mostly) able to excuse this stylistic quirk because Bromley writes so acutely about herself and others, giving a lucid sense of the passage of time and the particularities of place. She’s observant and funny, too. “I find what people often mean when they say ‘resilient’ is that they want people to be good at suffering in silence.” Youthful, playful, sexy: those are unusual characteristics for a book on the fringes of nature writing. The voice was distinctive enough that, though I’ve rarely met a 400+-page book that couldn’t stand to be closer to 300, I thoroughly enjoyed my time spent with it.

The Nero Awards judges chose an all-female inaugural shortlist made up of four works of opinionated nonfiction. I’ve read the first 42 pages of Undercurrent, Natasha Carthew’s memoir of growing up in poverty in Cornwall, and will probably leave it there; I didn’t care for the writing in Fern Brady’s Strong Female Character, her memoir of being a young autistic woman (it’s said to be funny but I didn’t get the humour). Hags, Victoria Smith’s book about the societal marginalizing of older women, is the sort of book I’d skim from the library but am unlikely to read in its entirety. I would have been very happy for Bromley to win.

With thanks to Coronet (Hodder & Stoughton) for the free copy for review.

The Fruit Cure by Jacqueline Alnes (Blog Tour)

Jacqueline Alnes was a college runner until she experienced a strange set of neurological symptoms: fainting, blurred vision, speech problems and seizures. Initially diagnosed with vestibular neuronitis, she later got on a waiting list for a hospital epilepsy unit. Her symptoms ebbed and flowed over the next few years. Sometimes she was well enough to get back to running – she completed a marathon in Washington, D.C. – but occasionally she was debilitated. Study abroad in Peru exacerbated her problems because of altitude sickness. She also spent time in a wheelchair. Chronic illness left her open to depression and self-harm, including disordered eating. This turned more extreme when she was drawn into the bizarre world of fruitarianism, which offered her structure and black-and-white logic.

Alongside her own story, Alnes tells that of a few eccentrics who were key in popularizing the all-fruit diet. In the 1950s, Essie Honiball (author of I Live on Fruit), an anorexic teacher pregnant by a married man, was preyed on by quack doctor Cornelius Dreyer, who had previously had patients die under his care. Dreyer was based in South Africa, but there were parallel movements in other countries, too. Veganism and the raw food diet came under the same general umbrella, but were not as exclusive. The other main characters in the narrative are “Freelee” (Leanne Ratcliffe) and “Durianrider” (Harley Johnstone), founders of the 30 Bananas a Day website, which swayed Alnes when she was desperate for a cure. They spread their evangelistic message via blogs, vlogs and conferences. Like any cult-like body, theirs hinged on control and fell victim to infighting and changes of direction over the years.

Alnes clearly hopes her own experience will be instructive, exposing the dangers of extreme treatments for vulnerable people:

Scammy cures have been here since the beginning of time and will continue to exist for as long as people do, but the more we can work to make our systems of healing more equitable for people, no matter [their] race, gender, class, sexual orientation, or body size, the less people will get caught up in harmful practices that end up hurting them in the end.

She effectively employs metaphors from the Book of Genesis, likening early-years Durianrider and Freelee to Adam and Eve (them of the forbidden fruit) and pondering her own illness-origin story:

There are endless ways to write an origin story. Over the years, I’ve succumbed to the temptation of rewriting this beginning, as if returning to that first night [she fell ill] will give me answers or allow me to change what happened. Instead, holes in the narrative emerge.

As will be familiar to readers of stories of chronic illness and disability, no clear answers emerge here. Alnes’ condition is up and down and there’s been no definitive cure. Like Essie, she was lured into adhering slavishly to a fruitarian diet for a time, but she now has a healthier, more flexible attitude towards food. I found I wasn’t particularly interested in reading about the central cranks, preferring to skip over the biographical material to follow the thread of Alnes’ own journey instead. The whole book seems a little too niche; a more generalist work about various radical health cures and their proponents may have engaged me more. Still, it was a reasonably interesting case study.

With thanks to Melville House Press for the proof copy for review.

Buy The Fruit Cure from Bookshop UK [affiliate link]

Related reading:

Heal Me by Julia Buckley

I was pleased to be part of the blog tour for The Fruit Cure. See below for details of where other reviews have appeared or will be appearing soon.

Some of you may know Lory, who is training as a spiritual director, from her blog,

Some of you may know Lory, who is training as a spiritual director, from her blog,

These 17 flash fiction stories fully embrace the possibilities of magic and weirdness, particularly to help us reconnect with the dead. Brad and I are literary acquaintances from our time working on (the now defunct) Bookkaholic web magazine in 2014–15. I liked this even more than his first book,

These 17 flash fiction stories fully embrace the possibilities of magic and weirdness, particularly to help us reconnect with the dead. Brad and I are literary acquaintances from our time working on (the now defunct) Bookkaholic web magazine in 2014–15. I liked this even more than his first book,  I had a misconception that each chapter would be written by a different author. I think that would actually have been the more interesting approach. Instead, each character is voiced by a different author, and sometimes by multiple authors across the 14 chapters (one per day) – a total of 36 authors took part. I soon wearied of the guess-who game. I most enjoyed the frame story, which was the work of Douglas Preston, a thriller author I don’t otherwise know.

I had a misconception that each chapter would be written by a different author. I think that would actually have been the more interesting approach. Instead, each character is voiced by a different author, and sometimes by multiple authors across the 14 chapters (one per day) – a total of 36 authors took part. I soon wearied of the guess-who game. I most enjoyed the frame story, which was the work of Douglas Preston, a thriller author I don’t otherwise know.

My last unread book by Ansell (whose

My last unread book by Ansell (whose  At a confluence of Southern, Black and gay identities, Kinard writes of matriarchal families, of congregations and choirs, of the descendants of enslavers and enslaved living side by side. The layout mattered more than I knew, reading an e-copy: often it is white text on a black page; words form rings or an infinity symbol; erasure poems gray out much of what has come before. “Boomerang” interludes imagine a chorus of fireflies offering commentary – just one of numerous insect metaphors. Mythology also plays a role. “A Tangle of Gorgons,” a sample poem I’d read before, wends its serpentine way across several pages. “Catalog of My Obsessions or Things I Answer to” presents an alphabetical list. For the most part, the poems were longer, wordier and more involved (four pages of notes on the style and allusions) than I tend to prefer, but I could appreciate the religious frame of reference and the alliteration.

At a confluence of Southern, Black and gay identities, Kinard writes of matriarchal families, of congregations and choirs, of the descendants of enslavers and enslaved living side by side. The layout mattered more than I knew, reading an e-copy: often it is white text on a black page; words form rings or an infinity symbol; erasure poems gray out much of what has come before. “Boomerang” interludes imagine a chorus of fireflies offering commentary – just one of numerous insect metaphors. Mythology also plays a role. “A Tangle of Gorgons,” a sample poem I’d read before, wends its serpentine way across several pages. “Catalog of My Obsessions or Things I Answer to” presents an alphabetical list. For the most part, the poems were longer, wordier and more involved (four pages of notes on the style and allusions) than I tend to prefer, but I could appreciate the religious frame of reference and the alliteration. “Immanuel was the centre of the world once. Long after it imploded, its gravitational pull remains.” McNaught grew up in an evangelical church in Winchester, England, but by the time he left for university he’d fallen away. Meanwhile, some peers left for Nigeria to become disciples at charismatic preacher TB Joshua’s Synagogue Church of All Nations in Lagos. It’s obvious to outsiders that this was a cult, but not so to those caught up in it. It took years and repeated allegations for people to wake up to faked healings, sexual abuse, and the ceding of control to a megalomaniac who got rich off of duping and exploiting followers. This book won the inaugural Fitzcarraldo Editions Essay Prize. I admired its blend of journalistic and confessional styles: research, interviews with friends and strangers alike, and reflection on the author’s own loss of faith. He gets to the heart of why people stayed: “A feeling of holding and of being held. A sense of fellowship and interdependence … the rare moments of transcendence … It was nice to be a superorganism.” This gripped me from page one, but its wider appeal strikes me as limited. For me, it was the perfect chance to think about how I might write about traditions I grew up in and spurned.

“Immanuel was the centre of the world once. Long after it imploded, its gravitational pull remains.” McNaught grew up in an evangelical church in Winchester, England, but by the time he left for university he’d fallen away. Meanwhile, some peers left for Nigeria to become disciples at charismatic preacher TB Joshua’s Synagogue Church of All Nations in Lagos. It’s obvious to outsiders that this was a cult, but not so to those caught up in it. It took years and repeated allegations for people to wake up to faked healings, sexual abuse, and the ceding of control to a megalomaniac who got rich off of duping and exploiting followers. This book won the inaugural Fitzcarraldo Editions Essay Prize. I admired its blend of journalistic and confessional styles: research, interviews with friends and strangers alike, and reflection on the author’s own loss of faith. He gets to the heart of why people stayed: “A feeling of holding and of being held. A sense of fellowship and interdependence … the rare moments of transcendence … It was nice to be a superorganism.” This gripped me from page one, but its wider appeal strikes me as limited. For me, it was the perfect chance to think about how I might write about traditions I grew up in and spurned. Like other short works I’ve read by Hispanic women authors (

Like other short works I’ve read by Hispanic women authors ( I knew from

I knew from  The epigraph is from the two pages of laughter (“Ha!”) in “Real Estate,” one of the stories of

The epigraph is from the two pages of laughter (“Ha!”) in “Real Estate,” one of the stories of  This was a great collection of 33 stories, all of them beginning with the words “One Dollar” and most of flash fiction length. Bruce has a knack for quickly introducing a setup and protagonist. The voice and setting vary enough that no two stories sound the same. What is the worth of a dollar? In some cases, where there’s a more contemporary frame of reference, a dollar is a sign of desperation (for the man who’s lost house, job and wife in “Little Jimmy,” for the coupon-cutting penny-pincher whose unbroken monologue makes up the whole of “Grocery List”), or maybe just enough for a small treat for a child (as in “Mouse Socks” or “Boogie Board”). In the historical stories, a dollar can buy a lot more. It’s a tank of gas – and a lesson on the evils of segregation – in “Gas Station”; it’s a huckster’s exorbitant charge for a mocked-up relic in “The Grass Jesus Walked On.”

This was a great collection of 33 stories, all of them beginning with the words “One Dollar” and most of flash fiction length. Bruce has a knack for quickly introducing a setup and protagonist. The voice and setting vary enough that no two stories sound the same. What is the worth of a dollar? In some cases, where there’s a more contemporary frame of reference, a dollar is a sign of desperation (for the man who’s lost house, job and wife in “Little Jimmy,” for the coupon-cutting penny-pincher whose unbroken monologue makes up the whole of “Grocery List”), or maybe just enough for a small treat for a child (as in “Mouse Socks” or “Boogie Board”). In the historical stories, a dollar can buy a lot more. It’s a tank of gas – and a lesson on the evils of segregation – in “Gas Station”; it’s a huckster’s exorbitant charge for a mocked-up relic in “The Grass Jesus Walked On.”

Taking a long walk through London one day, Khaled looks back from midlife on the choices he and his two best friends have made. He first came to the UK as an eighteen-year-old student at Edinburgh University. Everything that came after stemmed from one fateful day. Matar places Khaled and his university friend Mustafa at a real-life demonstration outside the Libyan embassy in London in 1984, which ended in a rain of bullets and the accidental death of a female police officer. Khaled’s physical wound is less crippling than the sense of being cut off from his homeland and his family. As he continues his literary studies and begins teaching, he decides to keep his injury a secret from them, as from nearly everyone else in his life. On a trip to Paris to support a female friend undergoing surgery, he happens to meet Hosam, a writer whose work enraptured him when he heard it on the radio back home long ago. Decades pass and the Arab Spring prompts his friends to take different paths.

Taking a long walk through London one day, Khaled looks back from midlife on the choices he and his two best friends have made. He first came to the UK as an eighteen-year-old student at Edinburgh University. Everything that came after stemmed from one fateful day. Matar places Khaled and his university friend Mustafa at a real-life demonstration outside the Libyan embassy in London in 1984, which ended in a rain of bullets and the accidental death of a female police officer. Khaled’s physical wound is less crippling than the sense of being cut off from his homeland and his family. As he continues his literary studies and begins teaching, he decides to keep his injury a secret from them, as from nearly everyone else in his life. On a trip to Paris to support a female friend undergoing surgery, he happens to meet Hosam, a writer whose work enraptured him when he heard it on the radio back home long ago. Decades pass and the Arab Spring prompts his friends to take different paths. A second problem: Covid-19 stories feel dated. For the first two years of the pandemic I read obsessively about it, mostly nonfiction accounts from healthcare workers or ordinary people looking for community or turning to nature in a time of collective crisis. But now when I come across it as a major element in a book, it feels like an out-of-place artefact; I’m almost embarrassed for the author: so sorry, but you missed your moment. My disappointment may primarily be because my expectations were so high. I’ve noted that two blogger friends new to Nunez were enthusiastic about this (but so was

A second problem: Covid-19 stories feel dated. For the first two years of the pandemic I read obsessively about it, mostly nonfiction accounts from healthcare workers or ordinary people looking for community or turning to nature in a time of collective crisis. But now when I come across it as a major element in a book, it feels like an out-of-place artefact; I’m almost embarrassed for the author: so sorry, but you missed your moment. My disappointment may primarily be because my expectations were so high. I’ve noted that two blogger friends new to Nunez were enthusiastic about this (but so was  From one November to the next, he watches the seasons advance and finds many magical spaces with everyday wonders to appreciate. “This project was already beginning to challenge my assumptions of what was beautiful or natural in the landscape,” he writes in his second week. True, he also finds distressing amounts of litter, no-access signs and evidence of environmental degradation. But curiosity is his watchword: “The more I pay attention, the more I notice. The more I notice, the more I learn.”

From one November to the next, he watches the seasons advance and finds many magical spaces with everyday wonders to appreciate. “This project was already beginning to challenge my assumptions of what was beautiful or natural in the landscape,” he writes in his second week. True, he also finds distressing amounts of litter, no-access signs and evidence of environmental degradation. But curiosity is his watchword: “The more I pay attention, the more I notice. The more I notice, the more I learn.” Jones is now a mother of three. You might think delivery would get easier each time, but in fact the birth of her second son was worst, physically: she had to go into immediate surgery for a fourth-degree anal sphincter tear. In reflecting on her own experiences, and speaking with experts, she has become passionate about fostering open discussion about the pain and risk of childbirth, and how to mitigate them. Women who aren’t informed about what they might go through suffer more because of the shock and isolation. There’s the medical side, but also the equally important social implications: new mothers need so much more practical and mental health support, and their unpaid care work must be properly valued by society. “Yet the focus remains on individual responsibility, maintaining the illusion that we are impermeable, impenetrable machines, disconnected from the world around us.”

Jones is now a mother of three. You might think delivery would get easier each time, but in fact the birth of her second son was worst, physically: she had to go into immediate surgery for a fourth-degree anal sphincter tear. In reflecting on her own experiences, and speaking with experts, she has become passionate about fostering open discussion about the pain and risk of childbirth, and how to mitigate them. Women who aren’t informed about what they might go through suffer more because of the shock and isolation. There’s the medical side, but also the equally important social implications: new mothers need so much more practical and mental health support, and their unpaid care work must be properly valued by society. “Yet the focus remains on individual responsibility, maintaining the illusion that we are impermeable, impenetrable machines, disconnected from the world around us.” Kinsella is an Irish poet who became a mother in her mid-twenties; that’s young these days. In unchronological vignettes dated in relation to her son’s birth – the number of months after; negative numbers to indicate that it happened before – she explores her personality, mental health and bodily experiences, but also comments more widely on Irish culture (the stereotype of the ‘mammy’; the only recent closure of Magdalene laundries and overturning of anti-abortion laws) and theories about motherhood.

Kinsella is an Irish poet who became a mother in her mid-twenties; that’s young these days. In unchronological vignettes dated in relation to her son’s birth – the number of months after; negative numbers to indicate that it happened before – she explores her personality, mental health and bodily experiences, but also comments more widely on Irish culture (the stereotype of the ‘mammy’; the only recent closure of Magdalene laundries and overturning of anti-abortion laws) and theories about motherhood. I’ve read one of Kirsty Logan’s novels and dipped into her short stories. I immediately knew her parenting memoir would be up my street, but wondered how her fantasy/horror style might translate into nonfiction. Second-person narration is perfect for describing her journey into motherhood: a way of capturing the bewildering weirdness of this time but also forcing the reader to experience it firsthand. It is, in a way, as feminist and surreal as her other work. “You and your partner want a baby. But your two bodies can’t make a baby together. So you need some sperm.” That opening paragraph is a jolt, and the frank present-tense storytelling carries all through.

I’ve read one of Kirsty Logan’s novels and dipped into her short stories. I immediately knew her parenting memoir would be up my street, but wondered how her fantasy/horror style might translate into nonfiction. Second-person narration is perfect for describing her journey into motherhood: a way of capturing the bewildering weirdness of this time but also forcing the reader to experience it firsthand. It is, in a way, as feminist and surreal as her other work. “You and your partner want a baby. But your two bodies can’t make a baby together. So you need some sperm.” That opening paragraph is a jolt, and the frank present-tense storytelling carries all through. Procreation. Duplication. Imitation. All three connotations are appropriate for the title of an allusive novel about motherhood and doppelgangers. A pregnant writer starts composing a novel about Mary Shelley and finds the borders between fiction and (auto)biography blurring: “parts of her story detached themselves from the page and clung to my life.” The first long chapter, “Conception,” is full of biographical information about Shelley and the writing and plot of Frankenstein, chiming with

Procreation. Duplication. Imitation. All three connotations are appropriate for the title of an allusive novel about motherhood and doppelgangers. A pregnant writer starts composing a novel about Mary Shelley and finds the borders between fiction and (auto)biography blurring: “parts of her story detached themselves from the page and clung to my life.” The first long chapter, “Conception,” is full of biographical information about Shelley and the writing and plot of Frankenstein, chiming with