Last House Before the Mountain by Monika Helfer (#NovNov23 and #GermanLitMonth)

This Austrian novella, originally published in German in 2020, also counts towards German Literature Month, hosted by Lizzy Siddal. It is Helfer’s fourth book but first to become available in English translation. I picked it up on a whim from a charity shop.

“Memory has to be seen as utter chaos. Only when a drama is made out of it is some kind of order established.”

A family saga in miniature, this has the feel of a family memoir, with the author frequently interjecting to say what happened later or who a certain character would become, yet the focus on climactic scenes – reimagined through interviews with her Aunt Kathe – gives it the shape of autofiction.

Josef and Maria Moosbrugger live on the outskirts of an alpine village with their four children. The book’s German title, Die Bagage, literally means baggage or bearers (Josef’s ancestors were itinerant labourers), but with the connotation of riff-raff, it is applied as an unkind nickname to the impoverished family. When Josef is called up to fight in the First World War, life turns perilous for the beautiful Maria. Rumours spread about her entertaining men up at their remote cottage, such that Josef doubts the parentage of the next child (Grete, Helfer’s mother) conceived during one of his short periods of leave. Son Lorenz resorts to stealing food, and has to defend his mother against the mayor’s advances with a shotgun.

If you look closely at the cover, you’ll see it’s peopled with figures from Pieter Bruegel’s Children’s Games. Helfer was captivated by the thought of her mother and aunts and uncles as carefree children at play. And despite the challenges and deprivations of the war years, you do get the sense that this was a joyful family. But I wondered if the threats were too easily defused. They were never going to starve because others brought them food; the fending-off-the-mayor scenes are played for laughs even though he very well could have raped Maria.

Helfer’s asides (“But I am getting ahead of myself”) draw attention to how she took this trove of family stories and turned them into a narrative. I found that the meta moments interrupted the flow and made me less involved in the plot because I was unconvinced that the characters really did and said what she posits. In short, I would probably have preferred either a straightforward novella inspired by wartime family history, or a short family memoir with photographs, rather than this betwixt-and-between document.

(Bloomsbury, 2023. Translated from the German by Gillian Davidson. Secondhand purchase from Bas Books and Home, Newbury.) [175 pages]

Three in Translation for #NovNov23: Baek, de Beauvoir, Naspini

I’m kicking off Week 3 of Novellas in November, which we’ve dubbed “Broadening My Horizons.” You can interpret that however you like, but Cathy and I have suggested that you might like to review some works in translation and/or think about any new genres or authors you’ve been introduced to through novellas. Literature in translation is still at the edge of my comfort zone, so it’s good to have excuses such as this (and Women in Translation Month each August) to pick up books originally published in another language. Later in the week I’ll have a contribution or two for German Lit Month too.

I Want to Die but I Want to Eat Tteokbokki by Baek Se-hee (2018; 2022)

[Translated from the Korean by Anton Hur]

Best title ever. And a really appealing premise, but it turns out that transcripts of psychiatry appointments are kinda boring. (What a lazy way to put a book together, huh?) Nonetheless, I remained engaged with this because the thoughts and feelings she expresses are so relatable that I kept finding myself or other people I know in them. Themes that emerge include co-dependent relationships, pathological lying, having impossibly high standards for oneself and others, extreme black-and-white thinking, the need for attention, and the struggle to develop a meaningful career in publishing.

Best title ever. And a really appealing premise, but it turns out that transcripts of psychiatry appointments are kinda boring. (What a lazy way to put a book together, huh?) Nonetheless, I remained engaged with this because the thoughts and feelings she expresses are so relatable that I kept finding myself or other people I know in them. Themes that emerge include co-dependent relationships, pathological lying, having impossibly high standards for oneself and others, extreme black-and-white thinking, the need for attention, and the struggle to develop a meaningful career in publishing.

There are bits of context and reflection, but I didn’t get a clear overall sense of the author as a person, just as a bundle of neuroses. Her psychiatrist tells her “writing can be a way of regarding yourself three-dimensionally,” which explains why I’ve started journaling – that, and I want believe that the everyday matters, and that it’s important to memorialize.

I think the book could have ended with Chapter 14, the note from her psychiatrist, instead of continuing with another 30+ pages of vague self-help chat. This is such an unlikely bestseller (to the extent that a sequel was published, by the same title, just with “Still” inserted!); I have to wonder if some of its charm simply did not translate. (Public library) [194 pages]

The Inseparables by Simone de Beauvoir (2020; 2021)

[Translated from the French by Lauren Elkin]

Earlier this year I read my first work by de Beauvoir, also of novella length, A Very Easy Death, a memoir of losing her mother. This is in the same autobiographical mode: a lightly fictionalized story of her intimate friendship with Elisabeth Lacoin (nicknamed “Zaza”) from ages 10 to 21, written in 1954 but not published until recently. The author’s stand-in is Sylvie and Zaza is Andrée. When they meet at school, Sylvie is immediately enraptured by her bold, talented friend. “Many of her opinions were subversive, but because she was so young, the teachers forgave her. ‘This child has a lot of personality,’ they said at school.” Andrée takes a lot of physical risks, once even deliberately cutting her foot with an axe to get out of a situation (Zaza really did this, too).

Earlier this year I read my first work by de Beauvoir, also of novella length, A Very Easy Death, a memoir of losing her mother. This is in the same autobiographical mode: a lightly fictionalized story of her intimate friendship with Elisabeth Lacoin (nicknamed “Zaza”) from ages 10 to 21, written in 1954 but not published until recently. The author’s stand-in is Sylvie and Zaza is Andrée. When they meet at school, Sylvie is immediately enraptured by her bold, talented friend. “Many of her opinions were subversive, but because she was so young, the teachers forgave her. ‘This child has a lot of personality,’ they said at school.” Andrée takes a lot of physical risks, once even deliberately cutting her foot with an axe to get out of a situation (Zaza really did this, too).

Whereas Sylvie loses her Catholic faith (“at one time, I had loved both Andrée and God with ferocity”), Andrée remains devout. She seems destined to follow her older sister, Malou, into a safe marriage, but before that has a couple of unsanctioned romances with her cousin, Bernard, and with Pascal (based on Maurice Merleau-Ponty). Sylvie observes these with a sort of detached jealousy. I expected her obsessive love for Andrée to turn sexual, as in Emma Donoghue’s Learned by Heart, but it appears that it did not, in life or in fiction. In fact, Elkin reveals in a translator’s note that the girls always said “vous” to each other, rather than the more familiar form of you, “tu.” How odd that such stiffness lingered between them.

This feels fragmentary, unfinished. De Beauvoir wrote about Zaza several times, including in Memoirs of a Dutiful Daughter, but this was her fullest tribute. Its length, I suppose, is a fitting testament to a friendship cut short. (Passed on by Laura – thank you!) [137 pages]

(Introduction by Deborah Levy; afterword by Sylvie Le Bon de Beauvoir, de Beavoir’s adopted daughter. North American title: Inseparable.)

Tell Me About It by Sacha Naspini (2020; 2022)

[Translated from the Italian by Clarissa Botsford]

The Tuscan novelist’s second work to appear in English has an irresistible setup: Nives, recently widowed, brings her pet chicken Giacomina into the house as a companion. One evening, while a Tide commercial plays on the television, Giacomina goes as still as a statue. Nives places a call to Loriano Bottai, the local vet and an old family friend who is known to spend every night inebriated, to ask for advice, but they stay on the phone for hours as one topic leads to another. Readers learn much about these two, whom, it soon emerges, have a history.

The Tuscan novelist’s second work to appear in English has an irresistible setup: Nives, recently widowed, brings her pet chicken Giacomina into the house as a companion. One evening, while a Tide commercial plays on the television, Giacomina goes as still as a statue. Nives places a call to Loriano Bottai, the local vet and an old family friend who is known to spend every night inebriated, to ask for advice, but they stay on the phone for hours as one topic leads to another. Readers learn much about these two, whom, it soon emerges, have a history.

The text is saturated with dialogue; quick wits and sharp tempers blaze. You could imagine this as a radio or stage play. The two characters discuss their children and the town’s scandals, including a lothario turned artist’s muse and a young woman who died by suicide. “The past is full of ghosts. For all of us. That’s how it is, and that’s how it will always be,” Loriano says. There’s a feeling of catharsis to getting all these secrets out into the open. But is there a third person on the line?

A couple of small translation issues hampered my enjoyment: the habit of alternating between calling him Loriano and Bottai (whereas Nives is always that), and the preponderance of sayings (“What’s true is that the business with the nightie has put a bee in my bonnet”), which is presumably to mimic the slang of the original but grates. Still, a good read. (Passed on by Annabel – thank you!) [128 pages]

#WITMonth, Part II: Wioletta Greg, Dorthe Nors, Almudena Sánchez and More

My next four reads for Women in Translation month (after Part I here) were, again, a varied selection: a mixed volume of family history in verse and fragmentary diary entries, a set of nature/travel essays set mostly in Denmark, a memoir of mental illness, and a preview of a forthcoming novel about Mary Shelley’s inspirations for Frankenstein. One final selection will be coming up as part of my Love Your Library roundup on Monday.

(20 Books of Summer, #13)

Finite Formulae & Theories of Chance by Wioletta Greg (2014)

[Translated from the Polish by Marek Kazmierski]

I loved Greg’s Swallowing Mercury so much that I jumped at the chance to read something else of hers in English translation – plus this was less than half price AND a signed copy. I had no sense of the contents and might have reconsidered had I known a few things: the first two-thirds is family wartime history in verse, the rest is a fragmentary diary from eight years in which Greg lived on the Isle of Wight, and the book is a bilingual edition, with Polish and English on facing pages (for the poems) or one after the other (for the diary entries). I’m not sure what this format adds for English-language readers; I can’t know whether Kazmierski has rendered anything successfully. I’ve always thought it must be next to impossible to translate poetry, and it’s certainly hard to assess these as poems. They are fairly interesting snapshots from her family’s history, e.g., her grandfather’s escape from a stalag, and have quite precise vocabulary for the natural world. There’s also been an attempt to create or reproduce alliteration. I liked the poem the title phrase comes from, “A Fairytale about Death,” and “Readers.” The short diary entries, though, felt entirely superfluous. (New purchase – Waterstones bargain, 2023)

I loved Greg’s Swallowing Mercury so much that I jumped at the chance to read something else of hers in English translation – plus this was less than half price AND a signed copy. I had no sense of the contents and might have reconsidered had I known a few things: the first two-thirds is family wartime history in verse, the rest is a fragmentary diary from eight years in which Greg lived on the Isle of Wight, and the book is a bilingual edition, with Polish and English on facing pages (for the poems) or one after the other (for the diary entries). I’m not sure what this format adds for English-language readers; I can’t know whether Kazmierski has rendered anything successfully. I’ve always thought it must be next to impossible to translate poetry, and it’s certainly hard to assess these as poems. They are fairly interesting snapshots from her family’s history, e.g., her grandfather’s escape from a stalag, and have quite precise vocabulary for the natural world. There’s also been an attempt to create or reproduce alliteration. I liked the poem the title phrase comes from, “A Fairytale about Death,” and “Readers.” The short diary entries, though, felt entirely superfluous. (New purchase – Waterstones bargain, 2023)

(20 Books of Summer, #14)

A Line in the World: A Year on the North Sea Coast by Dorthe Nors (2021; 2022)

[Translated from the Danish by Caroline Waight]

Nors’s first nonfiction work is a surprise entry on this year’s Wainwright Prize nature writing shortlist. I’d be delighted to see this work in translation win, first because it would send a signal that it is not a provincial award, and secondly because her writing is stunning. Like Patrick Leigh Fermor, Aldo Leopold or Peter Matthiessen, she doesn’t just report what she sees but thinks deeply about what it means and how it connects to memory or identity. I have a soft spot for such philosophizing in nature and travel writing.

Nors’s first nonfiction work is a surprise entry on this year’s Wainwright Prize nature writing shortlist. I’d be delighted to see this work in translation win, first because it would send a signal that it is not a provincial award, and secondly because her writing is stunning. Like Patrick Leigh Fermor, Aldo Leopold or Peter Matthiessen, she doesn’t just report what she sees but thinks deeply about what it means and how it connects to memory or identity. I have a soft spot for such philosophizing in nature and travel writing.

You carry the place you come from inside you, but you can never go back to it.

I longed … to live my brief and arbitrary life while I still have it.

This eternal, fertile and dread-laden stream inside us. This fundamental question: do you want to remember or forget?

Nors lives in rural Jutland – where she grew up, before her family home was razed – along the west coast of Denmark, the same coast that reaches down to Germany and the Netherlands. In comparison to Copenhagen and Amsterdam, two other places she’s lived, it’s little visited and largely unknown to foreigners. This can be both good and bad. Tourists feel they’re discovering somewhere new, but the residents are insular – Nors is persona non grata for at least a year and a half simply for joking about locals’ exaggerated fear of wolves.

Local legends and traditions, bird migration, reliance on the sea, wanderlust, maritime history, a visit to church frescoes with Signe Parkins (the book’s illustrator), the year’s longest and shortest days … I started reading this months ago and set it aside for a time, so now find it difficult to remember what some of the essays are actually about. They’re more about the atmosphere, really: the remote seaside, sometimes so bleak as to seem like the ends of the earth. (It’s why I like reading about Scottish islands.) A bit more familiarity with the places Nors writes about would have pushed my rating higher, but her prose is excellent throughout. I also marked the metaphors “A local woman is standing there with a hairstyle like a wolverine” and “The sky looks like dirty mop-water.”

With thanks to Pushkin Press for the proof copy for review.

Pharmakon by Almudena Sánchez (2021; 2023)

[Translated from the Spanish by Katie Whittemore]

This is a memoir in micro-essays about the author’s experience of mental illness, as she tries to write herself away from suicidal thoughts. She grew up on Mallorca, always feeling like an outsider on an island where she wasn’t a native. Did her depression stem from her childhood, she wonders? She is also a survivor of ovarian cancer, diagnosed when she was 16. As her mind bounces from subject to subject, “trying to analyze a sick brain,” she documents her doctor visits, her medications, her dreams, her retweets, and much more. She takes inspiration from famous fellow depressives such as William Styron and Virginia Woolf. Her household is obsessed with books, she says, and it’s mostly through literature that she understands her life. The writing can be poetic, but few pieces stand out on the whole. My favourite opens: “Living in between anxiety and apathy has driven me to flowerpot decorating.”

This is a memoir in micro-essays about the author’s experience of mental illness, as she tries to write herself away from suicidal thoughts. She grew up on Mallorca, always feeling like an outsider on an island where she wasn’t a native. Did her depression stem from her childhood, she wonders? She is also a survivor of ovarian cancer, diagnosed when she was 16. As her mind bounces from subject to subject, “trying to analyze a sick brain,” she documents her doctor visits, her medications, her dreams, her retweets, and much more. She takes inspiration from famous fellow depressives such as William Styron and Virginia Woolf. Her household is obsessed with books, she says, and it’s mostly through literature that she understands her life. The writing can be poetic, but few pieces stand out on the whole. My favourite opens: “Living in between anxiety and apathy has driven me to flowerpot decorating.”

With thanks to Fum d’Estampa Press for the free copy for review.

And a bonus preview:

Mary and the Birth of Frankenstein by Anne Eekhout (2021; 2023)

[Translated from the Dutch by Laura Watkinson]

Anne Eekhout’s fourth novel and English-language debut is an evocative recreation of two momentous periods in Mary Shelley’s life that led – directly or indirectly – to the composition of her 1818 masterpiece. Drawing parallels between the creative process and motherhood and presenting a credibly queer slant on history, the book is full of eerie encounters and mysterious phenomena that replicate the Gothic science fiction tone of Frankenstein itself. The story lines are set in the famous “Year without a Summer” of 1816 (the storytelling challenge with Lord Byron) and during a period in 1812 that she spent living in Scotland with the Baxter family; Mary falls in love with the 17-year-old daughter, Isabella.

Anne Eekhout’s fourth novel and English-language debut is an evocative recreation of two momentous periods in Mary Shelley’s life that led – directly or indirectly – to the composition of her 1818 masterpiece. Drawing parallels between the creative process and motherhood and presenting a credibly queer slant on history, the book is full of eerie encounters and mysterious phenomena that replicate the Gothic science fiction tone of Frankenstein itself. The story lines are set in the famous “Year without a Summer” of 1816 (the storytelling challenge with Lord Byron) and during a period in 1812 that she spent living in Scotland with the Baxter family; Mary falls in love with the 17-year-old daughter, Isabella.

Coming out on 3 October from HarperVia. My full review for Shelf Awareness is pending.

February Releases by Nick Acheson, Charlotte Eichler and Nona Fernández (#ReadIndies)

Three final selections for Read Indies. I’m pleased to have featured 16 books from independent publishers this month. And how’s this for neat symmetry? I started the month with Chase of the Wild Goose and finish with a literal wild goose chase as Nick Acheson tracks down Norfolk’s flocks in the lockdown winter of 2020–21. Also appearing today are nature- and travel-filled poems and a hybrid memoir about Chilean and family history.

The Meaning of Geese: A thousand miles in search of home by Nick Acheson

I saw Nick Acheson speak at New Networks for Nature 2021 as the ‘anti-’ voice in a debate on ecotourism. He was a wildlife guide in South America and Africa for more than a decade before, waking up to the enormity of the climate crisis, he vowed never to fly again. Now he mostly stays close to home in North Norfolk, where he grew up and where generations of his family have lived and farmed, working for Norfolk Wildlife Trust and appreciating the flora and fauna on his doorstep.

This was indeed to be a low-carbon initiative, undertaken on his mother’s 40-year-old red bicycle and spanning September 2021 to the start of the following spring. Whether on his own or with friends and experts, and in fair weather or foul, he became obsessed with spending as much time observing geese as he could – even six hours at a stretch. Pink-footed geese descend on the Holkham Estate in their thousands, but there were smaller flocks and rarer types as well: from Canada and greylag to white-fronted and snow geese. He also found perspective (historical, ethical and geographical) by way of Peter Scott’s conservation efforts, chats with hunters, and insight from the Icelandic researchers who watch the geese later in the year, after they leave the UK. The germane context is woven into a month-by-month diary.

This was indeed to be a low-carbon initiative, undertaken on his mother’s 40-year-old red bicycle and spanning September 2021 to the start of the following spring. Whether on his own or with friends and experts, and in fair weather or foul, he became obsessed with spending as much time observing geese as he could – even six hours at a stretch. Pink-footed geese descend on the Holkham Estate in their thousands, but there were smaller flocks and rarer types as well: from Canada and greylag to white-fronted and snow geese. He also found perspective (historical, ethical and geographical) by way of Peter Scott’s conservation efforts, chats with hunters, and insight from the Icelandic researchers who watch the geese later in the year, after they leave the UK. The germane context is woven into a month-by-month diary.

The Covid-19 lockdowns spawned a number of nature books in the UK – for instance, I’ve also read Goshawk Summer by James Aldred, Birdsong in a Time of Silence by Steven Lovatt, The Consolation of Nature by Michael McCarthy, Jeremy Mynott and Peter Marren, and Skylarks with Rosie by Stephen Moss – and although the pandemic is not a major element here, one does get a sense of how Acheson struggled with isolation as well as the normal winter blues and found comfort and purpose in birdwatching.

Tundra bean, taiga bean, brent … I don’t think I’ve seen any of these species – not even pinkfeet, to my recollection – so wished for black-and-white drawings or colour photographs in the book. That’s not to say that Acheson is not successful at painting word pictures of geese; his rich descriptions, full of food-related and sartorial metaphors, are proof of how much he revels in the company of birds. But I suspect this is a book more for birders than for casual nature-watchers like myself. I would have welcomed more autobiographical material, and Wintering by Stephen Rutt seems the more suitable geese book for laymen. Still, I admire Acheson’s fervour: “I watch birds not to add them to a list of species seen; nor to sneer at birds which are not truly wild. I watch them because they are magnificent”.

With thanks to Chelsea Green Publishing for the free copy for review.

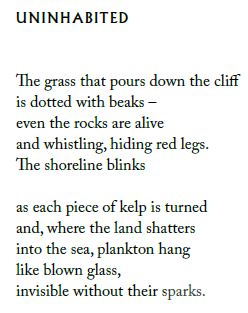

Swimming Between Islands by Charlotte Eichler

Eichler’s debut collection was inspired by various trips to cold and remote places, such as to Lofoten 10 years ago, as she explains in a blog post on the Carcanet website. (The cover image is her painting Nusfjord.) British and Scandinavian islands and their wildlife provide much of the imagery and atmosphere. You can sink into the moss and fog, lulled by alliteration. A glance at some of the poem titles reveals the breadth of her gaze: “Brimstones” – “A Pheasant” (a perfect description in just two lines) – “A Meditation of Small Frogs” – “Trapping Moths with My Father.” There are also historical vignettes and pen portraits. The scenes of childhood, as in the four-part “What Little Girls Are Made Of,” evoke the freedom of curiosity about the natural world and feel autobiographical yet universal.

Eichler’s debut collection was inspired by various trips to cold and remote places, such as to Lofoten 10 years ago, as she explains in a blog post on the Carcanet website. (The cover image is her painting Nusfjord.) British and Scandinavian islands and their wildlife provide much of the imagery and atmosphere. You can sink into the moss and fog, lulled by alliteration. A glance at some of the poem titles reveals the breadth of her gaze: “Brimstones” – “A Pheasant” (a perfect description in just two lines) – “A Meditation of Small Frogs” – “Trapping Moths with My Father.” There are also historical vignettes and pen portraits. The scenes of childhood, as in the four-part “What Little Girls Are Made Of,” evoke the freedom of curiosity about the natural world and feel autobiographical yet universal.

With thanks to Carcanet Press for the free copy for review.

Voyager: Constellations of Memory—A Memoir by Nona Fernández (2019; 2023)

[Translated from the Spanish by Natasha Wimmer]

Our archive of memories is the closest thing we have to a record of identity. … Disjointed fragments, a pile of mirror shards, a heap of the past. The accumulation is what we’re made of.

When Fernández’s elderly mother started fainting and struggling with recall, it prompted the Chilean actress and writer to embark on an inquiry into memory. Astronomy provides the symbolic language here, with memory a constellation and gaps as black holes. But the stars also play a literal role. Fernández was part of an Amnesty International campaign to rename a constellation in honour of the 26 people “disappeared” in Chile’s Atacama Desert in 1973. She meets the widow of one of the victims, wondering what he might have been like as an older man as she helps to plan the star ceremony. This oblique and imaginative narrative ties together brain evolution, a medieval astronomer executed for heresy, Pinochet administration collaborators, her son’s birth, and her mother’s surprise 80th birthday party. NASA’s Voyager probes, launched in 1977, were intended as time capsules capturing something of human life at the time. The author imagines her brief memoir doing the same: “A book is a space-time capsule. It freezes the present and launches it into tomorrow as a message.”

When Fernández’s elderly mother started fainting and struggling with recall, it prompted the Chilean actress and writer to embark on an inquiry into memory. Astronomy provides the symbolic language here, with memory a constellation and gaps as black holes. But the stars also play a literal role. Fernández was part of an Amnesty International campaign to rename a constellation in honour of the 26 people “disappeared” in Chile’s Atacama Desert in 1973. She meets the widow of one of the victims, wondering what he might have been like as an older man as she helps to plan the star ceremony. This oblique and imaginative narrative ties together brain evolution, a medieval astronomer executed for heresy, Pinochet administration collaborators, her son’s birth, and her mother’s surprise 80th birthday party. NASA’s Voyager probes, launched in 1977, were intended as time capsules capturing something of human life at the time. The author imagines her brief memoir doing the same: “A book is a space-time capsule. It freezes the present and launches it into tomorrow as a message.”

With thanks to Daunt Books for the free copy for review.

#ReadIndies and Review Catch-up: Hazrat, Nettel, Peacock, Seldon

Another four selections for Read Indies month. I’m particularly pleased that two from this latest batch are “just because” books that I picked up off my shelves; another two are catch-up review copies. A few more indie titles will appear in my February roundup on Tuesday. For today, I have a fun variety: a history of the exclamation point, a Mexican novel about choosing motherhood versus being childfree, a memoir of a decades-long friendship between two poets, and a posthumous poetry collection with themes of history, illness and nature.

An Admirable Point: A brief history of the exclamation mark by Florence Hazrat (2022)

I’m definitely a punctuation geek. (My favourite punctuation mark is the semicolon, and there’s a book about it, too: Semicolon: The Past, Present, and Future of a Misunderstood Mark by Cecelia Watson, which I have on my Kindle.) One might think that strings of exclamation points are a pretty new thing – rounding off phrases in (ex-)presidential tweets, for instance – but, in fact, Hazrat opens with a Boston Gazette headline from 1788 that decried “CORRUPTION AND BRIBERY!!!” in relation to the adoption of the new Constitution.

The exclamation mark as we know it has been around since 1399, and by the 16th century its use for expression and emphasis had been codified. I was reminded of Gretchen McCulloch’s discussion of emoji in Because Internet, which also considers how written speech signifies tone, especially in the digital age. There have been various proposals for other “intonation points” over the centuries, but the question mark and exclamation mark are the two that have stuck. (Though I’m currently listening to an album called interrobang – ‽, that is. Invented by Martin Speckter in 1962; recorded by Switchfoot in 2021.)

The exclamation mark as we know it has been around since 1399, and by the 16th century its use for expression and emphasis had been codified. I was reminded of Gretchen McCulloch’s discussion of emoji in Because Internet, which also considers how written speech signifies tone, especially in the digital age. There have been various proposals for other “intonation points” over the centuries, but the question mark and exclamation mark are the two that have stuck. (Though I’m currently listening to an album called interrobang – ‽, that is. Invented by Martin Speckter in 1962; recorded by Switchfoot in 2021.)

I most enjoyed Chapter 3, on punctuation in literature. Jane Austen’s original manuscripts, replete with dashes, ampersands and exclamation points, were tidied up considerably before they made it into book form. She’s literature’s third most liberal user of exclamation marks, in terms of the number per 100,000 words, according to a chart Ben Blatt drew up in 2017, topped only by Tom Wolfe and James Joyce.

There are also sections on the use of exclamation points in propaganda and political campaigns – in conjunction with fonts, which brought to mind Simon Garfield’s Just My Type and the graphic novel ABC of Typography. It might seem to have a niche subject, but at just over 150 pages this is a cheery and diverting read for word nerds.

With thanks to Profile Books for the proof copy for review.

Still Born by Guadalupe Nettel (2020; 2022)

[Translated from the Spanish by Rosalind Harvey]

This was the Mexican author’s fourth novel; she’s also a magazine director and has published several short story collections. I’d liken it to a cross between Motherhood by Sheila Heti and (the second half of) No One Is Talking About This by Patricia Lockwood. Thirtysomething friends Laura and Alina veer off in different directions, yet end up finding themselves in similar ethical dilemmas. Laura, who narrates, is adamant that she doesn’t want children, and follows through with sterilization. However, when she becomes enmeshed in a situation with her neighbours – Doris, who’s been left by her abusive husband, and her troubled son Nicolás – she understands some of the emotional burden of motherhood. Even the pigeon nest she watches on her balcony presents a sort of morality play about parenthood.

Meanwhile, Alina and her partner Aurelio embark on infertility treatment. Laura fears losing her friend: “Alina was about to disappear and join the sect of mothers, those creatures with no life of their own who, zombie-like, with huge bags under their eyes, lugged prams around the streets of the city.” They eventually have a daughter, Inés, but learn before her birth that brain defects may cause her to die in infancy or be severely disabled. Right from the start, Alina is conflicted. Will she cling to Inés no matter her condition, or let her go? And with various unhealthy coping mechanisms to hand, will her relationship with Aurelio stay the course?

Meanwhile, Alina and her partner Aurelio embark on infertility treatment. Laura fears losing her friend: “Alina was about to disappear and join the sect of mothers, those creatures with no life of their own who, zombie-like, with huge bags under their eyes, lugged prams around the streets of the city.” They eventually have a daughter, Inés, but learn before her birth that brain defects may cause her to die in infancy or be severely disabled. Right from the start, Alina is conflicted. Will she cling to Inés no matter her condition, or let her go? And with various unhealthy coping mechanisms to hand, will her relationship with Aurelio stay the course?

Laura alternates between her life and her friends’ circumstances, taking on an omniscient voice on Nettel’s behalf – she recounts details she couldn’t possibly be privy to, at least not at the time (there’s a similar strategy in The Group by Lara Feigel). The question of what is fated versus what is chosen, also represented by Laura’s interest in tarot and palm-reading, always appeals to me. This was a wry and sharp commentary on women’s options. (Giveaway win from Bookish Chat on Twitter)

Still Born was published by Fitzcarraldo Editions in the UK and is forthcoming from Bloomsbury in the USA on August 8th.

A Friend Sails in on a Poem by Molly Peacock (2022)

I’ve read one of Peacock’s poetry collections, The Analyst, as well as her biography of Mary Delany, The Paper Garden. I was delighted when she got in touch to offer a review copy of her latest memoir, which reflects on her nearly half a century of friendship with fellow poet Phillis Levin. They met in a Johns Hopkins University writing seminar in 1976, and ever since have shared their work in progress over meals. They are seven years apart in age and their careers took different routes – Peacock headed up the Poetry Society of America’s subway poetry project and then moved to Toronto, while Levin taught at the University of Maryland – but over the years they developed “a sense of trust that really does feel familial … There is a weird way, in our conversations about poetry, that we share a single soul.” For a time they were both based in New York City and had the same therapist; more recently, they arranged annual summer poetry retreats in Cazenovia (recalled via diary entries), with just the two attendees. Jobs and lovers came and went, but their bond has endured.

The book traces their lives but also their development as poets, through examples of their verse. Her friend is “Phillis” in real life, but “Levin” when it’s her work is being discussed – and her own poems are as written by “Peacock.” Both women became devoted to the sonnet, an unusual choice because at the time that they were graduate students free verse reigned and form was something one had to learn on one’s own time. Stanza means “room,” Peacock reminds readers, and she believes there is something about form that opens up space, almost literally but certainly metaphorically, to re-examine experience. She repeatedly tracks how traumatic childhood events, as much as everyday observations, were transmuted into her poetry. Levin did so, too, but with an opposite approach: intellectual and universal where Peacock was carnal and personal. That paradox of difference yet likeness is the essence of the friendships we sail on. What a lovely read, especially if you’re curious about ‘where poems come from’; I’d particularly recommend it to fans of Ann Patchett’s Truth and Beauty.

The book traces their lives but also their development as poets, through examples of their verse. Her friend is “Phillis” in real life, but “Levin” when it’s her work is being discussed – and her own poems are as written by “Peacock.” Both women became devoted to the sonnet, an unusual choice because at the time that they were graduate students free verse reigned and form was something one had to learn on one’s own time. Stanza means “room,” Peacock reminds readers, and she believes there is something about form that opens up space, almost literally but certainly metaphorically, to re-examine experience. She repeatedly tracks how traumatic childhood events, as much as everyday observations, were transmuted into her poetry. Levin did so, too, but with an opposite approach: intellectual and universal where Peacock was carnal and personal. That paradox of difference yet likeness is the essence of the friendships we sail on. What a lovely read, especially if you’re curious about ‘where poems come from’; I’d particularly recommend it to fans of Ann Patchett’s Truth and Beauty.

With thanks to Molly Peacock and Palimpsest Press for the free e-copy for review.

The Bright White Tree by Joanna Seldon (Worple Press, 2017)

This appeared the year after Seldon died of cancer; were it not for her untimely end and her famous husband Anthony (a historian and political biographer), I’m not sure it would have been published, as the poetry is fairly mediocre, with some obvious rhymes and twee sentiments. I wouldn’t want to speak ill of the dead, though, so think of this more like a self-published work collected in tribute, and then no problem. Some of the poems were written from the Royal Marsden Hospital, with “Advice” a useful rundown of how to be there for a friend undergoing cancer treatment (text to let them know you’re thinking of them; check before calling, or visiting briefly; bring sanctioned snacks; don’t be afraid to ask after their health).

Seldon takes inspiration from history (the story of Kitty Pakenham, the bombing of the Bamiyan Buddhas), travels in England and abroad (“Robin in York” vs. “Tuscan Garden”), and family history. Her Jewish heritage is clear from poems about Israel, National Holocaust Memorial Day and Rosh Hashanah. Her own suffering is put into perspective in “A Cancer Patient Visits Auschwitz.” There are also ekphrastic responses to art and literature (a Gaugin, A Winter’s Tale, Jane Eyre, and so on). I particularly liked “Conker,” a reminder of a departed loved one “So is a good life packed full of doing / That may grow warm with others, even when / The many years have turned, and darkness filled / Places where memory shone bright and strong. / I feel the conker and feel he is here.” (New bargain book from Waterstones online sale with Christmas book token)

Seldon takes inspiration from history (the story of Kitty Pakenham, the bombing of the Bamiyan Buddhas), travels in England and abroad (“Robin in York” vs. “Tuscan Garden”), and family history. Her Jewish heritage is clear from poems about Israel, National Holocaust Memorial Day and Rosh Hashanah. Her own suffering is put into perspective in “A Cancer Patient Visits Auschwitz.” There are also ekphrastic responses to art and literature (a Gaugin, A Winter’s Tale, Jane Eyre, and so on). I particularly liked “Conker,” a reminder of a departed loved one “So is a good life packed full of doing / That may grow warm with others, even when / The many years have turned, and darkness filled / Places where memory shone bright and strong. / I feel the conker and feel he is here.” (New bargain book from Waterstones online sale with Christmas book token)

There are haikus dotted through the collection; here’s one perfect for the season:

“Snowdrops Haiku”

Maids demure, white tips to

Mob caps… Look now! They’ve

Splattered the lawn with snow

Have you discovered any new-to-you independent publishers recently?

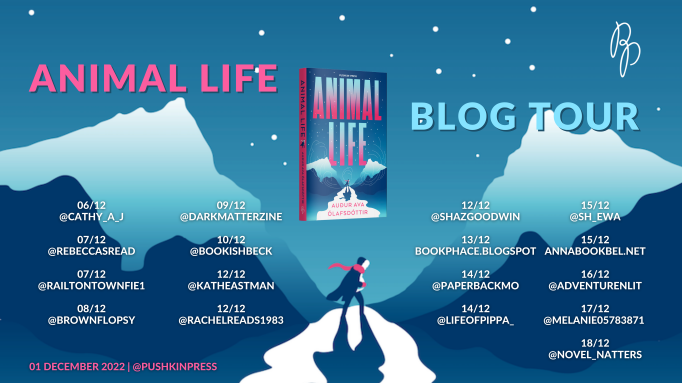

Animal Life by Auður Ava Ólafsdóttir

Icelandic author Auður Ava Ólafsdóttir was familiar to me from Butterflies in November (2013), a whimsical, feminist road trip novel I reviewed for For Books’ Sake. Dómhildur or “Dýja” is, like her grandaunt before her, a midwife – a word that was once voted Iceland’s most beautiful: ljósmóðir combines the words for light and mother, so it connotes “mother of light.” On the other side of the family, Dýja’s relatives are undertakers, a neat setup that sees her clan “handling people at their points of entry and exit.”

Along with her profession, Dýja inherited her great-aunt’s apartment, nine bottles of sherry, pen pal letters to a Welsh midwife and a box containing several discursive manuscripts of philosophical musings, one of them entitled Animal Life. In fragments from this book within the book, we see how her grandaunt recorded philosophical musings about coincidences and humanity in relation to other species, vacillating between the poetic and the scientific.

Along with her profession, Dýja inherited her great-aunt’s apartment, nine bottles of sherry, pen pal letters to a Welsh midwife and a box containing several discursive manuscripts of philosophical musings, one of them entitled Animal Life. In fragments from this book within the book, we see how her grandaunt recorded philosophical musings about coincidences and humanity in relation to other species, vacillating between the poetic and the scientific.

As Christmas – and an unprecedented storm prophesied by her meteorologist sister – approaches, Dýja starts to make the apartment less of a mausoleum and more her own home, trading lots of the fusty furniture for a colleague’s help with painting and decorating, and flirting with an Australian tourist who’s staying in the apartment upstairs. Outside of work she has never had much of a personal life, so she’s finally finding a better balance.

I really warmed to the grandaunt character and enjoyed the peppering of her aphorisms. As in novels like The Birth House and A Ghost in the Throat, it feels like this is a female wisdom, somewhat forbidden and witchy. The idea of it being passed down through the generations is appealing. We get less of a sense of Dýja overall, only late on finding that she has her own traumatic backstory. For a first-person narrator, she’s lacking the expected interiority. Mostly, we see her interactions with a random selection of minor characters such as an electrician whose wife is experiencing postpartum depression.

I felt there were a few too many disparate elements here, not all joined but just left on the page as a quirky smorgasbord. Still, it’s fun to try fiction in translation sometimes, especially when it’s of novella length. This also reminded me a bit of Weather and Brood.

Translated by Brian FitzGibbon. With thanks to Pushkin Press for my free copy for review.

I was delighted to be part of the blog tour for Animal Life. See below for details of where other reviews have appeared or will be appearing soon.

I reviewed Lane’s debut novel,

I reviewed Lane’s debut novel,  I’d read fiction and nonfiction from Lerner but had no idea of what to expect from his poetry. Almost every other poem is a prose piece, many of these being absurdist monologues that move via word association between topics seemingly chosen at random: psychoanalysis, birdsong, his brother’s colorblindness; proverbs, the Holocaust; art conservation, his partner’s upcoming C-section, an IRS Schedule C tax form, and so on.

I’d read fiction and nonfiction from Lerner but had no idea of what to expect from his poetry. Almost every other poem is a prose piece, many of these being absurdist monologues that move via word association between topics seemingly chosen at random: psychoanalysis, birdsong, his brother’s colorblindness; proverbs, the Holocaust; art conservation, his partner’s upcoming C-section, an IRS Schedule C tax form, and so on. Mahdavian has also published comics in the New Yorker. His debut graphic novel is a memoir of the three years (2016–19) he and his wife lived in remote Idaho. Of Iranian heritage, the author had lived in Miami and then the Bay Area, so was pretty unprepared for living off-grid. His wife, Emelie (who is white), is a documentary filmmaker. They had a box house brought in on a trailer. After Trump’s surprise win, it was a challenging time to be a Brown man in the rural USA. “You’re not a Muslim, are you?” was the kind of question he got on their trips into town. Neighbors were outwardly friendly – bringing them firewood and elk kebabs, helping when their car wouldn’t start or they ran off the road in icy conditions, teaching them the local bald eagles’ habits – yet thought nothing of making racist and homophobic slurs.

Mahdavian has also published comics in the New Yorker. His debut graphic novel is a memoir of the three years (2016–19) he and his wife lived in remote Idaho. Of Iranian heritage, the author had lived in Miami and then the Bay Area, so was pretty unprepared for living off-grid. His wife, Emelie (who is white), is a documentary filmmaker. They had a box house brought in on a trailer. After Trump’s surprise win, it was a challenging time to be a Brown man in the rural USA. “You’re not a Muslim, are you?” was the kind of question he got on their trips into town. Neighbors were outwardly friendly – bringing them firewood and elk kebabs, helping when their car wouldn’t start or they ran off the road in icy conditions, teaching them the local bald eagles’ habits – yet thought nothing of making racist and homophobic slurs. Enright’s astute eighth novel traces the family legacies of talent and trauma through the generations descended from a famous Irish poet. Cycles of abandonment and abuse characterize the McDaraghs. Enright convincingly pinpoints the narcissism and codependency behind their love-hate relationships. (It was an honor to also interview Anne Enright. You can see our Q&A

Enright’s astute eighth novel traces the family legacies of talent and trauma through the generations descended from a famous Irish poet. Cycles of abandonment and abuse characterize the McDaraghs. Enright convincingly pinpoints the narcissism and codependency behind their love-hate relationships. (It was an honor to also interview Anne Enright. You can see our Q&A  This lyrical debut memoir is an experimental, literary recounting of the experience of undergoing a stroke and relearning daily skills while supporting a gender-transitioning partner. Fraser splits herself into two: the “I” moving through life, and “Ghost,” her memory repository. But “I can’t rely only on Ghost’s mental postcards,” Fraser thinks, and sets out to retrieve evidence of who she was and is.

This lyrical debut memoir is an experimental, literary recounting of the experience of undergoing a stroke and relearning daily skills while supporting a gender-transitioning partner. Fraser splits herself into two: the “I” moving through life, and “Ghost,” her memory repository. But “I can’t rely only on Ghost’s mental postcards,” Fraser thinks, and sets out to retrieve evidence of who she was and is. (Already featured in my

(Already featured in my  A collection of 15 thoughtful nature/travel essays that explore the interconnectedness of life and conservation strategies, and exemplify compassion for people and, particularly, animals. The book makes a round-trip journey, beginning at Quade’s Ohio farm and venturing further afield in the Americas and to Southeast Asia before returning home.

A collection of 15 thoughtful nature/travel essays that explore the interconnectedness of life and conservation strategies, and exemplify compassion for people and, particularly, animals. The book makes a round-trip journey, beginning at Quade’s Ohio farm and venturing further afield in the Americas and to Southeast Asia before returning home. The lovely laments in Brian Turner’s fourth collection (a sequel to

The lovely laments in Brian Turner’s fourth collection (a sequel to  A new Logistics Centre is to cut through Anaïs’s family vineyards as part of a compulsory land purchase. While her father, Magí, and brother, Jan, are resigned to the loss, this single mother decides to resist, tying herself to a stone shed on the premises that will be right in the path of the bulldozers. This causes others to question her mental health, with social worker Elisa tasked with investigating the case. Key evidence of her irrational behaviour turns out to have perfectly good explanations.

A new Logistics Centre is to cut through Anaïs’s family vineyards as part of a compulsory land purchase. While her father, Magí, and brother, Jan, are resigned to the loss, this single mother decides to resist, tying herself to a stone shed on the premises that will be right in the path of the bulldozers. This causes others to question her mental health, with social worker Elisa tasked with investigating the case. Key evidence of her irrational behaviour turns out to have perfectly good explanations. In October 1963, de Beauvoir was in Rome when she got a call informing her that her mother had had an accident. Expecting the worst, she was relieved – if only temporarily – to hear that it was a fall at home, resulting in a broken femur. But when Françoise de Beauvoir got to the hospital, what at first looked like peritonitis was diagnosed as stomach cancer with an intestinal obstruction. Her daughters knew that she was dying, but she had no idea (from what I’ve read, this paternalistic notion that patients must be treated like children and kept ignorant of their prognosis is more common on the Continent, and continues even today).

In October 1963, de Beauvoir was in Rome when she got a call informing her that her mother had had an accident. Expecting the worst, she was relieved – if only temporarily – to hear that it was a fall at home, resulting in a broken femur. But when Françoise de Beauvoir got to the hospital, what at first looked like peritonitis was diagnosed as stomach cancer with an intestinal obstruction. Her daughters knew that she was dying, but she had no idea (from what I’ve read, this paternalistic notion that patients must be treated like children and kept ignorant of their prognosis is more common on the Continent, and continues even today). My sixth Moomins book, and ninth by Jansson overall. The novella’s gentle peril is set in motion by the discovery of the Hobgoblin’s Hat, which transforms anything placed within it. As spring moves into summer, this causes all kind of mild mischief until Thingumy and Bob, who speak in spoonerisms, show up with a suitcase containing something desired by both the Groke and the Hobgoblin, and make a deal that stops the disruptions.

My sixth Moomins book, and ninth by Jansson overall. The novella’s gentle peril is set in motion by the discovery of the Hobgoblin’s Hat, which transforms anything placed within it. As spring moves into summer, this causes all kind of mild mischief until Thingumy and Bob, who speak in spoonerisms, show up with a suitcase containing something desired by both the Groke and the Hobgoblin, and make a deal that stops the disruptions. I tend to love a memoir that tries something new or experimental with the form (such as

I tend to love a memoir that tries something new or experimental with the form (such as

In the inventive debut novel by Mexican author Jazmina Barrera, a sudden death provokes an intricate examination of three young women’s years of shifting friendship. Their shared hobby of embroidery occasions a history of women’s handiwork, woven into a relationship study that will remind readers of works by Elena Ferrante and Deborah Levy. Citlali, Dalia, and Mila had been best friends since middle school. Mila, a writer with a young daughter, is blindsided by news that Citlali has drowned off Senegal. While waiting to be reunited with Dalia for Citlali’s memorial service, she browses her journal to revisit key moments from their friendship, especially travels in Europe and to a Mexican village. Cross-stitch becomes its own metaphorical language, passed on by female ancestors and transmitted across social classes. Reminiscent of Still Born and A Ghost in the Throat. (Edelweiss)

In the inventive debut novel by Mexican author Jazmina Barrera, a sudden death provokes an intricate examination of three young women’s years of shifting friendship. Their shared hobby of embroidery occasions a history of women’s handiwork, woven into a relationship study that will remind readers of works by Elena Ferrante and Deborah Levy. Citlali, Dalia, and Mila had been best friends since middle school. Mila, a writer with a young daughter, is blindsided by news that Citlali has drowned off Senegal. While waiting to be reunited with Dalia for Citlali’s memorial service, she browses her journal to revisit key moments from their friendship, especially travels in Europe and to a Mexican village. Cross-stitch becomes its own metaphorical language, passed on by female ancestors and transmitted across social classes. Reminiscent of Still Born and A Ghost in the Throat. (Edelweiss)

Berger (1926–2017), an art critic and Booker Prize-winning novelist, spent six weeks shadowing the doctor, to whom he gives the pseudonym John Sassall, with Swiss documentary photographer Jean Mohr, his frequent collaborator. Sassall’s dedication was legendary: he attended every birth in this community, and nearly every death. Sassall’s middle-class origins set him apart from his patients. There’s something condescending about how Berger depicts the locals as simple peasants. Mohr’s photos include soft-focus close-ups on faces exhibiting a sequence of emotions, a technique that feels outdated in the age of video. Along with recording the day-to-day details of medical complaints and interventions, Berger waxes philosophical on topics such as infirmity and vocation. A Fortunate Man is a curious book, part intellectual enquiry and part hagiography.

Berger (1926–2017), an art critic and Booker Prize-winning novelist, spent six weeks shadowing the doctor, to whom he gives the pseudonym John Sassall, with Swiss documentary photographer Jean Mohr, his frequent collaborator. Sassall’s dedication was legendary: he attended every birth in this community, and nearly every death. Sassall’s middle-class origins set him apart from his patients. There’s something condescending about how Berger depicts the locals as simple peasants. Mohr’s photos include soft-focus close-ups on faces exhibiting a sequence of emotions, a technique that feels outdated in the age of video. Along with recording the day-to-day details of medical complaints and interventions, Berger waxes philosophical on topics such as infirmity and vocation. A Fortunate Man is a curious book, part intellectual enquiry and part hagiography.  With its layers of local history and its braided biographical strands, A Fortunate Woman takes up many of the same heavy questions but feels more subtle and timely. It also soon delivers a jolting surprise: the doctor Berger called John Sassall was likely bipolar and, soon after the death of his beloved wife Betty, committed suicide in 1982. His story still haunts this community, where many of the older patients remember going to him for treatment. Like Berger, Morland keenly follows a range of cases. As the book progresses, we see this beautiful valley cycle through the seasons, with certain of Richard Baker’s landscape shots deliberately recreating Mohr’s scene setting. The timing of Morland’s book means that it morphs from a portrait of the quotidian for a doctor and a community to, two-thirds through, an incidental record of the challenges of medical practice during COVID-19.

With its layers of local history and its braided biographical strands, A Fortunate Woman takes up many of the same heavy questions but feels more subtle and timely. It also soon delivers a jolting surprise: the doctor Berger called John Sassall was likely bipolar and, soon after the death of his beloved wife Betty, committed suicide in 1982. His story still haunts this community, where many of the older patients remember going to him for treatment. Like Berger, Morland keenly follows a range of cases. As the book progresses, we see this beautiful valley cycle through the seasons, with certain of Richard Baker’s landscape shots deliberately recreating Mohr’s scene setting. The timing of Morland’s book means that it morphs from a portrait of the quotidian for a doctor and a community to, two-thirds through, an incidental record of the challenges of medical practice during COVID-19.

Galbraith’s is an elegiac tour through imperilled countryside and urban edgelands. Each chapter resembles an in-depth magazine article: a carefully crafted profile of a beloved bird species, with a focus on the specific threats it faces. Galbraith recognises the nuances of land use. However, shooting plays an outsized role. (Curious for his bio not to disclose that he is editor of the Shooting Times.) The title’s reference is to literal birdsong, but the book also celebrates birds’ cultural importance through their place in Britain’s folk music and poetry. He is clearly enamoured of countryside ways, but too often slips into laddishness, with no opportunity missed to mention him or another man having a “piss” outside. Readers could also be forgiven for concluding that “Ilka” (no surname, affiliation or job title), who briefs him on her research into kittiwake populations in Orkney, is the only female working in nature conservation in the entire country; with few exceptions, women only have bit parts: the farm wife making the tea, the receptionist on the phone line, and so on.

Galbraith’s is an elegiac tour through imperilled countryside and urban edgelands. Each chapter resembles an in-depth magazine article: a carefully crafted profile of a beloved bird species, with a focus on the specific threats it faces. Galbraith recognises the nuances of land use. However, shooting plays an outsized role. (Curious for his bio not to disclose that he is editor of the Shooting Times.) The title’s reference is to literal birdsong, but the book also celebrates birds’ cultural importance through their place in Britain’s folk music and poetry. He is clearly enamoured of countryside ways, but too often slips into laddishness, with no opportunity missed to mention him or another man having a “piss” outside. Readers could also be forgiven for concluding that “Ilka” (no surname, affiliation or job title), who briefs him on her research into kittiwake populations in Orkney, is the only female working in nature conservation in the entire country; with few exceptions, women only have bit parts: the farm wife making the tea, the receptionist on the phone line, and so on.  Pavelle’s book is a tonic in more ways than one. Employed by Beaver Trust, she is enthusiastic and self-deprecating. Her nature quest has a broader scope, including insects like the marsh fritillary and marine species such as seagrass and the Atlantic salmon. Travelling between lockdowns in 2020–1, Pavelle took low-carbon transport wherever possible and bolsters her trip accounts with context, much of it gleaned from Zoom calls and e-mail correspondence with experts from museums and universities. Refreshingly, around half of these interviewees are women, and the animal subjects are never the obvious choices. Instead, she seeks out “underdog” species. The explanations are at a suitable level for laymen, true to her job as a science communicator. The snappy, casual prose (“the future of the bilberry bumblebee and its Aperol arse can be bright, but only if we get off our own”) could even endear her to teenage readers. As image goes, Pavelle’s cheerful naïveté holds more charm than Galbraith’s hardboiled masculinity.

Pavelle’s book is a tonic in more ways than one. Employed by Beaver Trust, she is enthusiastic and self-deprecating. Her nature quest has a broader scope, including insects like the marsh fritillary and marine species such as seagrass and the Atlantic salmon. Travelling between lockdowns in 2020–1, Pavelle took low-carbon transport wherever possible and bolsters her trip accounts with context, much of it gleaned from Zoom calls and e-mail correspondence with experts from museums and universities. Refreshingly, around half of these interviewees are women, and the animal subjects are never the obvious choices. Instead, she seeks out “underdog” species. The explanations are at a suitable level for laymen, true to her job as a science communicator. The snappy, casual prose (“the future of the bilberry bumblebee and its Aperol arse can be bright, but only if we get off our own”) could even endear her to teenage readers. As image goes, Pavelle’s cheerful naïveté holds more charm than Galbraith’s hardboiled masculinity.  Taking Flight by Lev Parikian: Parikian’s accessible account of the animal kingdom’s development of flight exhibits a layman’s enthusiasm for an everyday wonder. He explicates the range of flying strategies and the structural adaptations that made them possible. The archaeopteryx section, chronicling the transition between dinosaurs and birds, is a highlight. Though the most science-heavy of the author’s six works, this, perhaps ironically, has fewer footnotes. His usual wit is on display: he describes the feral pigeon as “the Volkswagen Golf of birds” and penguins as “piebald blubber tubes”. This makes it a pleasure to tag along on a journey through evolutionary time, one sure to engage even history- and science-phobes.

Taking Flight by Lev Parikian: Parikian’s accessible account of the animal kingdom’s development of flight exhibits a layman’s enthusiasm for an everyday wonder. He explicates the range of flying strategies and the structural adaptations that made them possible. The archaeopteryx section, chronicling the transition between dinosaurs and birds, is a highlight. Though the most science-heavy of the author’s six works, this, perhaps ironically, has fewer footnotes. His usual wit is on display: he describes the feral pigeon as “the Volkswagen Golf of birds” and penguins as “piebald blubber tubes”. This makes it a pleasure to tag along on a journey through evolutionary time, one sure to engage even history- and science-phobes.