#ReadIndies Review Catch-Up: Chevillard, Hopkins & Bateman, McGrath, Richardson

Quick thoughts on some more review catch-up books, most of them from 2025. It’s a miscellaneous selection today: absurdist flash fiction by a prolific French author, a self-help graphic novel about surviving heartbreak, a blend of bird photography and poetry, and a debut poetry collection about life and death as encountered by a parish priest.

Museum Visits by Éric Chevillard (2024)

[Trans. from French by David Levin Becker]

I’d not heard of Chevillard, even though he’s published 22 novels and then some. This appealed to me because it’s a collection of micro-essays and short stories, many of them witty etymological or historical riffs. “The Guide,” a tongue-in-cheek tour of places where things may have happened, reminded me of Julian Barnes: “So, right here is where Henri IV ran a hand through his beard, here’s where a raindrop landed on Dante’s forehead, this is where Buster Keaton bit into a pancake” and so on. It’s a clever way of questioning what history has commemorated and whether it matters. Some pieces elaborate on a particular object – Hegel’s cap, a chair, stones, a mass attendance certificate. A concertgoer makes too much of the fact that they were born in the same year as the featured harpsichordist. “Autofiction” had me snorting with laughter, though it’s such a simple conceit. All Chevillard had to do in this authorial rundown of a coming of age was replace “write” with “ejaculate.” This leads to such ridiculous statements as “It was around this time that I began to want to publicly share what I was ejaculating” and “I ejaculate in all the major papers.” There are some great pieces about animals. Others outstayed their welcome, however, such as “Faldoni.” Most feel like intellectual experiments, which isn’t what you want all the time but is interesting to try for a change, so you might read one or two mini-narratives between other things.

I’d not heard of Chevillard, even though he’s published 22 novels and then some. This appealed to me because it’s a collection of micro-essays and short stories, many of them witty etymological or historical riffs. “The Guide,” a tongue-in-cheek tour of places where things may have happened, reminded me of Julian Barnes: “So, right here is where Henri IV ran a hand through his beard, here’s where a raindrop landed on Dante’s forehead, this is where Buster Keaton bit into a pancake” and so on. It’s a clever way of questioning what history has commemorated and whether it matters. Some pieces elaborate on a particular object – Hegel’s cap, a chair, stones, a mass attendance certificate. A concertgoer makes too much of the fact that they were born in the same year as the featured harpsichordist. “Autofiction” had me snorting with laughter, though it’s such a simple conceit. All Chevillard had to do in this authorial rundown of a coming of age was replace “write” with “ejaculate.” This leads to such ridiculous statements as “It was around this time that I began to want to publicly share what I was ejaculating” and “I ejaculate in all the major papers.” There are some great pieces about animals. Others outstayed their welcome, however, such as “Faldoni.” Most feel like intellectual experiments, which isn’t what you want all the time but is interesting to try for a change, so you might read one or two mini-narratives between other things.

With thanks to the University of Yale Press for the free copy for review.

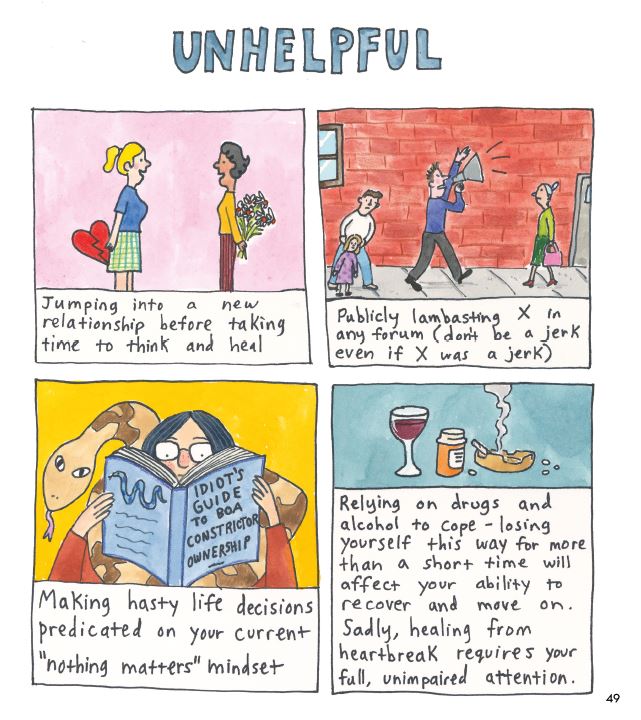

What to Do When You Get Dumped: A Guide to Unbreaking Your Heart by Suzy Hopkins; illus. Hallie Bateman (2025)

Discovered through Molly Wizenberg’s excellent author interview (she did a series on her Substack, “I’ve Got a Feeling”) with illustrator Hallie Bateman. It’s a mother–daughter collaboration – their second, after What to Do When I’m Gone, a funny advice guide that’s been likened to Roz Chast’s work (I’ve gotta get that one!). Hopkins’s husband of 30 years left her for an ex-girlfriend. (Ironic yet true: the girlfriend was a marriage counselor.) Composed while deep in grief, this is a frank look at the flood of emotions that accompany a breakup and gives wry but heartfelt suggestions for what might help: journaling, telling someone what happened, cleaning, making really easy to-do lists. Hopkins interviewed six others who had been dumped to get some extra perspective. Bateman describes her mother’s writing process: she made notes and stuck them in a shoebox with a hole in the lid, then went on a retreat to combine it all into a draft. At this point Bateman started illustrating. It was complicated for her, of course, because the dumper is her dad. She notes in the interview that she couldn’t just say “He’s an asshole” and dismiss him. But she could still position herself as a girlfriend to her mother, listening and commiserating. The vignettes are structured as a countdown starting with day 1,582 – it took over four years for Hopkins to come to terms with her loss and embrace a new life. This is a cute and gentle book that I wish had been around for my mom; it’s a heck of a lot cheaper than therapy.

Discovered through Molly Wizenberg’s excellent author interview (she did a series on her Substack, “I’ve Got a Feeling”) with illustrator Hallie Bateman. It’s a mother–daughter collaboration – their second, after What to Do When I’m Gone, a funny advice guide that’s been likened to Roz Chast’s work (I’ve gotta get that one!). Hopkins’s husband of 30 years left her for an ex-girlfriend. (Ironic yet true: the girlfriend was a marriage counselor.) Composed while deep in grief, this is a frank look at the flood of emotions that accompany a breakup and gives wry but heartfelt suggestions for what might help: journaling, telling someone what happened, cleaning, making really easy to-do lists. Hopkins interviewed six others who had been dumped to get some extra perspective. Bateman describes her mother’s writing process: she made notes and stuck them in a shoebox with a hole in the lid, then went on a retreat to combine it all into a draft. At this point Bateman started illustrating. It was complicated for her, of course, because the dumper is her dad. She notes in the interview that she couldn’t just say “He’s an asshole” and dismiss him. But she could still position herself as a girlfriend to her mother, listening and commiserating. The vignettes are structured as a countdown starting with day 1,582 – it took over four years for Hopkins to come to terms with her loss and embrace a new life. This is a cute and gentle book that I wish had been around for my mom; it’s a heck of a lot cheaper than therapy.

With thanks to Bloomsbury for the free e-copy for review.

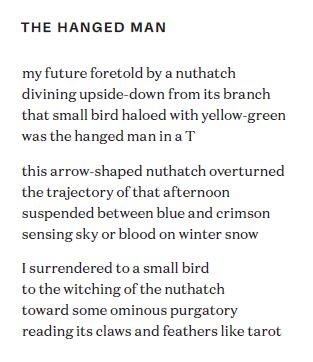

The Beauty of Vultures by Wendy McGrath; photos by Danny Miles (2025)

I enjoyed McGrath’s Santa Rosa trilogy and was keen to try her poetry, so I’m pleased that Marcie’s review pointed me here. McGrath came to collaborate with Miles, a musician, after her son told her of Miles’s newfound love of bird photography. She writes in her introduction that she wanted to go “beyond a simple call-and-response,” to instead use the photos as “portals” into art, history, memory, mythology, wordplay. The form varies to suit the topic: “sonnet, pantoum, acrostic, ghazal, concrete poem, … even a mini-play.” (I didn’t identify all of these on a first read, to be honest.) One poem imitates a matchbox cover and another is printed sideways. Most of the images are black-and-white close-ups, with a handful in colour. There are a few mammals as well as birds. One notable flash of colour is the recipient of the first poem, the sassy rebuttal “A Message from the Peahen to the Peacock.” The hen tells him to quit with the fancy displays and get real: “I’ve seen that gaudy display too often.”

I enjoyed McGrath’s Santa Rosa trilogy and was keen to try her poetry, so I’m pleased that Marcie’s review pointed me here. McGrath came to collaborate with Miles, a musician, after her son told her of Miles’s newfound love of bird photography. She writes in her introduction that she wanted to go “beyond a simple call-and-response,” to instead use the photos as “portals” into art, history, memory, mythology, wordplay. The form varies to suit the topic: “sonnet, pantoum, acrostic, ghazal, concrete poem, … even a mini-play.” (I didn’t identify all of these on a first read, to be honest.) One poem imitates a matchbox cover and another is printed sideways. Most of the images are black-and-white close-ups, with a handful in colour. There are a few mammals as well as birds. One notable flash of colour is the recipient of the first poem, the sassy rebuttal “A Message from the Peahen to the Peacock.” The hen tells him to quit with the fancy displays and get real: “I’ve seen that gaudy display too often.”

Other poems describe birds, address them directly, or take on their perspectives. Birds are a reassuring presence (cf. Ted Hughes on swifts): “I counted on our robins to return every spring” as a balm, the anxious speaker reports in “Air raid siren.” A nest of gape-mouthed baby swallows in an outhouse is the prize at the end of a long countryside walk. With its alliteration and repetition, “The Goldfinch Charm” feels like an incantation. Birds model grace (or at least the appearance of grace):

Assume a buoyancy, lightness, as though you were about to fly.

That yellow rubber duck is my surreal mythology.

Head above water. Stay calm. Paddle like crazy.

They link the natural world and the human in these gorgeous poems that interact with the images in ways that both lead and illuminate.

A female swan is a pen and eyes open

I try to write this dream:

a moment stolen or given.

Published by NeWest Press. With thanks to the author for the free e-copy for review.

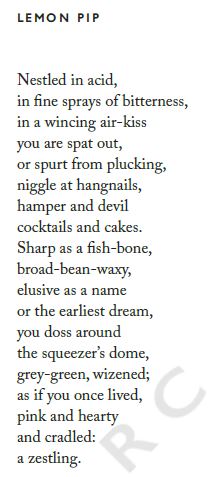

Dirt Rich by Graeme Richardson (2026)

Dirt poor? Nah. Miners, gravediggers and archaeologists will tell you that dirt is precious. It’s where lots of our food and minerals come from; it’s what we’ll return to – our bodies as well as the material traces of what we loved and cared for. Richardson, the poetry critic for the Sunday Times, comes from Nottinghamshire mining country and has worked as a chaplain and parish priest. He writes of church interiors and cemeteries, funerals and crumbling faith. There’s a harsh reminder of life’s unpredictability in the juxtaposition of “For the Album,” about the photographic evidence of a wedding day; and, beginning on the facing page, “After the Death of a Child.” It opens with “A Pastoral Heckle”: “The dead live on in memory? Not true. / They lodge there dead, and yours not theirs the hell.” Richardson now lives in Germany, so there are continental scenes as well as ecclesial English ones. The elegiac tone of standouts such as “Last of the Coalmine Choirboys” (with its words drawn from scripture and hymns) is tempered by the chaotic joy of multiple poems about parenthood in the final section. Throughout, the imagery and language glisten. I loved the slant rhyme, assonance and sibilance in “Rewilding the Churchyard”: “Cedars and self-seeders link / with the storm-forked sycamore.” I highly recommend this debut collection.

Dirt poor? Nah. Miners, gravediggers and archaeologists will tell you that dirt is precious. It’s where lots of our food and minerals come from; it’s what we’ll return to – our bodies as well as the material traces of what we loved and cared for. Richardson, the poetry critic for the Sunday Times, comes from Nottinghamshire mining country and has worked as a chaplain and parish priest. He writes of church interiors and cemeteries, funerals and crumbling faith. There’s a harsh reminder of life’s unpredictability in the juxtaposition of “For the Album,” about the photographic evidence of a wedding day; and, beginning on the facing page, “After the Death of a Child.” It opens with “A Pastoral Heckle”: “The dead live on in memory? Not true. / They lodge there dead, and yours not theirs the hell.” Richardson now lives in Germany, so there are continental scenes as well as ecclesial English ones. The elegiac tone of standouts such as “Last of the Coalmine Choirboys” (with its words drawn from scripture and hymns) is tempered by the chaotic joy of multiple poems about parenthood in the final section. Throughout, the imagery and language glisten. I loved the slant rhyme, assonance and sibilance in “Rewilding the Churchyard”: “Cedars and self-seeders link / with the storm-forked sycamore.” I highly recommend this debut collection.

With thanks to Carcanet Press for the advanced e-copy for review.

Which of these do you fancy reading?

The 2026 Releases I’ve Read So Far

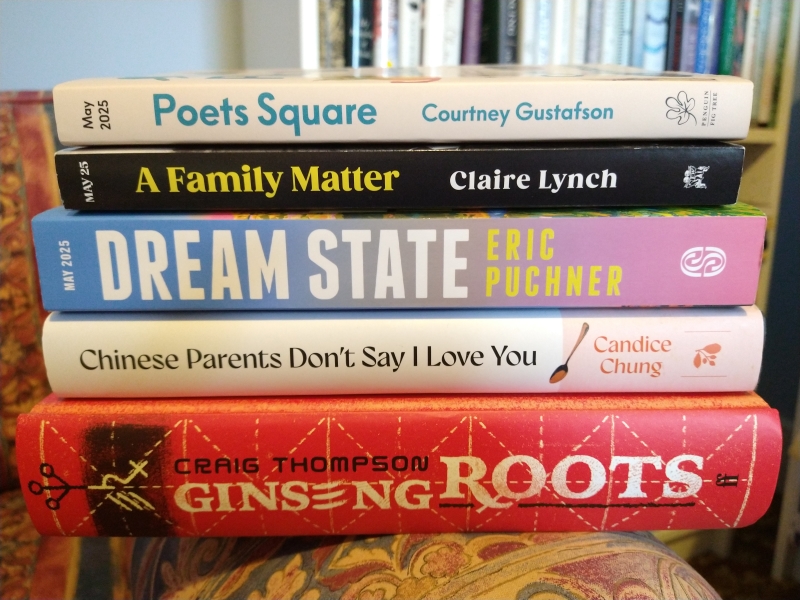

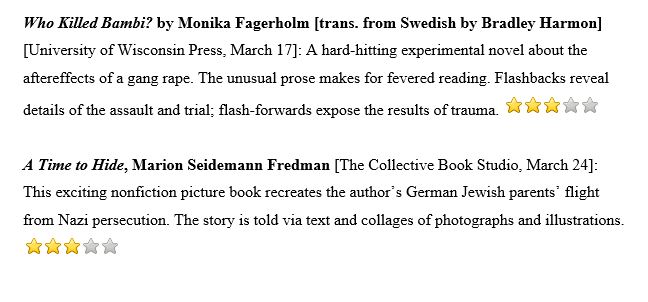

I happen to have read a number of pre-release books, generally for paid reviews for Foreword and Shelf Awareness. (I already previewed six upcoming novellas here.) Most of my reviews haven’t been published yet, so I’ll just give brief excerpts and ratings here to pique the interest. I link to the few that have been published already, then list the 2026 books I’m currently reading. Soon I’ll follow up with a list of my Most Anticipated titles.

Simple Heart by Cho Haejin (trans. from Korean by Jamie Chang) [Other Press, Feb. 3]: A transnational adoptee returns to Korea to investigate her roots through a documentary film. A poignant novel that explores questions of abandonment and belonging through stories of motherhood.

Simple Heart by Cho Haejin (trans. from Korean by Jamie Chang) [Other Press, Feb. 3]: A transnational adoptee returns to Korea to investigate her roots through a documentary film. A poignant novel that explores questions of abandonment and belonging through stories of motherhood. ![]()

The Conspiracists: Women, Extremism, and the Lure of Belonging by Noelle Cook [Broadleaf Books, Jan. 6]: An in-depth, empathetic study of “conspirituality” (a philosophy that blends conspiracy theories and New Age beliefs), filtered through the outlook of two women involved in storming the Capitol on January 6, 2021.

The Conspiracists: Women, Extremism, and the Lure of Belonging by Noelle Cook [Broadleaf Books, Jan. 6]: An in-depth, empathetic study of “conspirituality” (a philosophy that blends conspiracy theories and New Age beliefs), filtered through the outlook of two women involved in storming the Capitol on January 6, 2021. ![]()

The Reservation by Rebecca Kauffman [Counterpoint, Feb. 24]: The staff members of a fine-dining restaurant each have a moment in the spotlight during the investigation of a theft. Linked short stories depict character interactions and backstories with aplomb. Big-hearted; for J. Ryan Stradal fans.

The Reservation by Rebecca Kauffman [Counterpoint, Feb. 24]: The staff members of a fine-dining restaurant each have a moment in the spotlight during the investigation of a theft. Linked short stories depict character interactions and backstories with aplomb. Big-hearted; for J. Ryan Stradal fans. ![]()

Taking Flight by Kashmira Sheth (illus. Nicolo Carozzi) [Dial Press, April 21]: A touching story of the journeys of three refugee children who might be from Tibet, Syria and Ukraine. The drawing style reminded me of Chris Van Allsburg’s. This left a tear in my eye.

Taking Flight by Kashmira Sheth (illus. Nicolo Carozzi) [Dial Press, April 21]: A touching story of the journeys of three refugee children who might be from Tibet, Syria and Ukraine. The drawing style reminded me of Chris Van Allsburg’s. This left a tear in my eye. ![]()

Currently reading:

(Blurb excerpts from Goodreads; all are e-copies apart from Evensong)

Visitations: Poems by Julia Alvarez [Knopf, April 7]: “Alvarez traces her life [via] memories of her childhood in the Dominican Republic … and the sisters who forged her, her move to America …, the search for mental health and beauty, redemption, and success.”

Visitations: Poems by Julia Alvarez [Knopf, April 7]: “Alvarez traces her life [via] memories of her childhood in the Dominican Republic … and the sisters who forged her, her move to America …, the search for mental health and beauty, redemption, and success.”

Our Numbered Bones by Katya Balen [Canongate, 12 Feb. / HarperVia, Feb. 17]: Her “adult debut [is] about a grieving author who heads to rural England for a writer’s retreat, only to stumble upon an incredible historical find” – a bog body!

Our Numbered Bones by Katya Balen [Canongate, 12 Feb. / HarperVia, Feb. 17]: Her “adult debut [is] about a grieving author who heads to rural England for a writer’s retreat, only to stumble upon an incredible historical find” – a bog body!

Let’s Make Cocktails!: A Comic Book Cocktail Book by Sarah Becan [Ten Speed Press, April 7]: “With vivid, easy-to-follow graphics, Becan guides readers through basic techniques such as shaking, stirring, muddling, and more. With all recipes organized by spirit for easy access, readers will delight in the panelized step-by-step comic instructions.”

Let’s Make Cocktails!: A Comic Book Cocktail Book by Sarah Becan [Ten Speed Press, April 7]: “With vivid, easy-to-follow graphics, Becan guides readers through basic techniques such as shaking, stirring, muddling, and more. With all recipes organized by spirit for easy access, readers will delight in the panelized step-by-step comic instructions.”

Monsters in the Archives: My Year of Fear with Stephen King by Caroline Bicks [Hogarth/Hodder & Stoughton, April 21]: “A fascinating, first of its kind exploration of Stephen King and his … iconic early books, based on … research and interviews with King … conducted by the first scholar … given … access to his private archives.”

Monsters in the Archives: My Year of Fear with Stephen King by Caroline Bicks [Hogarth/Hodder & Stoughton, April 21]: “A fascinating, first of its kind exploration of Stephen King and his … iconic early books, based on … research and interviews with King … conducted by the first scholar … given … access to his private archives.”

Men I Hate: A Memoir in Essays by Lynette D’Amico [Mad Creek Books, Feb. 17]: “Can a lesbian who loves a trans man still call herself a lesbian? As D’Amico tries to engage more deeply with the man she is married to, she looks at all the men—historical figures, politicians, men in her family—in search of clear dividing lines”.

Men I Hate: A Memoir in Essays by Lynette D’Amico [Mad Creek Books, Feb. 17]: “Can a lesbian who loves a trans man still call herself a lesbian? As D’Amico tries to engage more deeply with the man she is married to, she looks at all the men—historical figures, politicians, men in her family—in search of clear dividing lines”.

See One, Do One, Teach One: The Art of Becoming a Doctor: A Graphic Memoir by Grace Farris [W. W. Norton & Company, March 24]: “In her graphic memoir debut, Grace looks back on her journey through medical school and residency.”

See One, Do One, Teach One: The Art of Becoming a Doctor: A Graphic Memoir by Grace Farris [W. W. Norton & Company, March 24]: “In her graphic memoir debut, Grace looks back on her journey through medical school and residency.”

Nighthawks by Lisa Martin [University of Alberta Press, April 2]: “These poems parse aspects of human embodiment—emotion, relationship, mortality—and reflect on how to live through moments of intense personal and political upheaval.”

Nighthawks by Lisa Martin [University of Alberta Press, April 2]: “These poems parse aspects of human embodiment—emotion, relationship, mortality—and reflect on how to live through moments of intense personal and political upheaval.”

Evensong by Stewart O’Nan [published in USA in November 2025; Grove Press UK, 1 Jan.]: “An intimate, moving novel that follows The Humpty Dumpty Club, a group of women of a certain age who band together to help one another and their circle of friends in Pittsburgh.”

Evensong by Stewart O’Nan [published in USA in November 2025; Grove Press UK, 1 Jan.]: “An intimate, moving novel that follows The Humpty Dumpty Club, a group of women of a certain age who band together to help one another and their circle of friends in Pittsburgh.”

This Is the Door: The Body, Pain, and Faith by Darcey Steinke [HarperOne, Feb. 24]: “In chapters that trace the body—The Spine, The Heart, The Knees, and more—[Steinke] introduces sufferers to new and ancient understandings of pain through history, philosophy, religion, pop culture, and reported human experience.”

This Is the Door: The Body, Pain, and Faith by Darcey Steinke [HarperOne, Feb. 24]: “In chapters that trace the body—The Spine, The Heart, The Knees, and more—[Steinke] introduces sufferers to new and ancient understandings of pain through history, philosophy, religion, pop culture, and reported human experience.”

American Fantasy by Emma Straub [Riverhead, April 7 / Michael Joseph (Penguin), 14 May]: “When the American Fantasy cruise ship sets sail for a four-day themed voyage, aboard are all five members of a famous 1990s boyband, and three thousand screaming women who have worshipped them for thirty years.”

American Fantasy by Emma Straub [Riverhead, April 7 / Michael Joseph (Penguin), 14 May]: “When the American Fantasy cruise ship sets sail for a four-day themed voyage, aboard are all five members of a famous 1990s boyband, and three thousand screaming women who have worshipped them for thirty years.”

Additional pre-release review books on my shelf:

Shooting Up by Jonathan Tepper [Constable, 19 Feb.]: “Born into a family of American missionaries driven by unwavering faith … Jonathan’s home became a sanctuary for society’s most broken … AIDS hit Spain a few years after it exploded in New York and, like an invisible plague, … claimed countless lives – including those … in the family rehabilitation centre.”

Shooting Up by Jonathan Tepper [Constable, 19 Feb.]: “Born into a family of American missionaries driven by unwavering faith … Jonathan’s home became a sanctuary for society’s most broken … AIDS hit Spain a few years after it exploded in New York and, like an invisible plague, … claimed countless lives – including those … in the family rehabilitation centre.”

Elizabeth and Ruth by Livi Michael [Salt Publishing, 9 Feb.]: “Based on the real correspondence between Elizabeth Gaskell and Charles Dickens … [Gaskell] visits a young Irish prostitute in Manchester’s New Bailey prison. … [A] story of hypocrisy and suppression, and how Elizabeth navigates the … prejudice of the day to help the young girl”.

Elizabeth and Ruth by Livi Michael [Salt Publishing, 9 Feb.]: “Based on the real correspondence between Elizabeth Gaskell and Charles Dickens … [Gaskell] visits a young Irish prostitute in Manchester’s New Bailey prison. … [A] story of hypocrisy and suppression, and how Elizabeth navigates the … prejudice of the day to help the young girl”.

Will you look out for one or more of these?

Any other 2026 reads you can recommend?

Sister Outsider by Audre Lorde (#NovNov25 Buddy Read, #NonfictionNovember)

This year we set two buddy reads for Novellas in November: one contemporary work of fiction (Seascraper) and one classic work of short nonfiction. Do let us know if you’ve been reading them and what you think!

Sister Outsider is a 1984 collection of Audre Lorde’s essays and speeches. Many of these short pieces appeared in Black or radical feminist magazines or scholarly journals, while a few give the text of her conference presentations. Lorde must have been one of the first writers to spotlight intersectionality: she ponders the combined effect of her Black lesbian identity on how she is perceived and what power she has in society.

The title’s paradox draws attention to the push and pull of solidarity and ostracism. She calls white feminists out for not considering what women of colour endure (or for making her a token Black speaker); she decries misogyny in the Black community; and she and her white lover, Frances, seem to attract homophobia from all quarters. Especially while trying to raise her Black teenage son to avoid toxic masculinity, the author comes to realise the importance of “learning to address each other’s difference with respect.”

This is a point she returns to again and again, and it’s as important now as it was when she was writing in the 1970s. So many forms of hatred and discrimination come down to difference being seen as a threat – “I disagree with you, so I must destroy you” is how she caricatures that perspective.

Even if you’ve never read a word that Lorde wrote, you probably know the phrase “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House” – this talk title refers to having to circumvent the racist patriarchy to truly fight oppression. “Revolution is not a one-time event,” she writes in another essay. “It is becoming always vigilant for the smallest opportunity to make a genuine change in established, outgrown responses”.

Even if you’ve never read a word that Lorde wrote, you probably know the phrase “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House” – this talk title refers to having to circumvent the racist patriarchy to truly fight oppression. “Revolution is not a one-time event,” she writes in another essay. “It is becoming always vigilant for the smallest opportunity to make a genuine change in established, outgrown responses”.

My two favourite pieces here also feel like they have entered into the zeitgeist. “Poetry Is Not a Luxury” deems poetry a “necessity for our existence … the way we help give name to the nameless so it can be thought.” And “Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power” is a thrilling redefinition of a holistic sensuality that means living at full tilt and tapping into creativity. “The sharing of joy, whether physical, emotional, psychic, or intellectual, forms a bridge between the sharers which can be the basis for understanding much of what is not shared”.

In some ways this is not an ideal way to be introduced to Lorde’s work, because many of the essays repeat the same themes and reasoning. I made my way through the book very slowly, one piece every day or few days. The speeches would almost certainly be more effective if heard aloud, as intended – and more provocative, too, as they must have undermined other speakers’ assumptions. I was also a bit taken aback by the opening and closing pieces being travelogues: “Notes from a Trip to Russia” is based on journal entries from 1976, while “Grenada Revisited: An Interim Report” about a 1983 trip to her mother’s birthplace. I saw more point to the latter, while the former felt somewhat out of place.

Nonetheless, Lorde’s thinking is essential and ahead of its time. I’d only previously read her short work The Cancer Journals. For years my book club has been toying with reading Zami, her memoir starting with growing up in 1930s Harlem, so I’ll hope to move that up the agenda for next year. Have you read any of her other books that you can recommend?(University library) [190 pages]

Other reviews of Sister Outsider:

Cathy (746 Books)

Marcie (Buried in Print) is making her way through the book one essay at a time. Here’s her latest post.

Four (Almost) One-Sitting Novellas by Blackburn, Murakami, Porter & School of Life (#NovNov25)

I never believe people who say they read 300-page novels in a sitting. How is that possible?! I’m a pretty slow reader, I like to bounce between books rather than read one exclusively, and I often have a hot drink to hand beside my book stack, so I’d need a bathroom break or two. I also have a young cat who doesn’t give me much peace. But 100 pages or thereabouts? I at least have a fighting chance of finishing a novella in one go. Although I haven’t yet achieved a one-sitting read this month, it’s always the goal: to carve out the time and be engrossed such that you just can’t put a book down. I’ll see if I can manage it before November is over.

A couple of longish car rides last weekend gave me the time to read most of three of these, and the next day I popped the other in my purse for a visit to my favourite local coffee shop. I polished them all off later in the week. I have a mini memoir in pets, a surreal Japanese story with illustrations, an innovative modern classic about bereavement, and a set of short essays about money and commodification.

My Animals and Other Family by Julia Blackburn; illus. Herman Makkink (2007)

In five short autobiographical essays, Blackburn traces her life with pets and other domestic animals. Guinea pigs taught her the facts of life when she was the pet monitor for her girls’ school – and taught her daughter the reality of death when they moved to the country and Galaxy sired a kingdom of outdoor guinea pigs. They also raised chickens, then adopted two orphaned fox cubs; this did not end well. There are intriguing hints of Blackburn’s childhood family dynamic, which she would later write about in the memoir The Three of Us: Her father was an alcoholic poet and her mother a painter. It was not a happy household and pets provided comfort as well as companionship. “I suppose tropical fish were my religion,” she remarks, remembering all the time she devoted to staring at the aquarium. Jason the spaniel was supposed to keep her safe on walks, but his presence didn’t deter a flasher (her parents’ and a policeman’s reactions to hearing the story are disturbingly blasé). My favourite piece was the first, “A Bushbaby from Harrods”: In the 1950s, the department store had a Zoo that sold exotic pets. Congo the bushbaby did his business all over her family’s flat but still was “the first great love of my life,” Blackburn insists. This was pleasant but won’t stay with me. (New purchase – remainder copy from Hay Cinema Bookshop, 2025) [86 pages]

In five short autobiographical essays, Blackburn traces her life with pets and other domestic animals. Guinea pigs taught her the facts of life when she was the pet monitor for her girls’ school – and taught her daughter the reality of death when they moved to the country and Galaxy sired a kingdom of outdoor guinea pigs. They also raised chickens, then adopted two orphaned fox cubs; this did not end well. There are intriguing hints of Blackburn’s childhood family dynamic, which she would later write about in the memoir The Three of Us: Her father was an alcoholic poet and her mother a painter. It was not a happy household and pets provided comfort as well as companionship. “I suppose tropical fish were my religion,” she remarks, remembering all the time she devoted to staring at the aquarium. Jason the spaniel was supposed to keep her safe on walks, but his presence didn’t deter a flasher (her parents’ and a policeman’s reactions to hearing the story are disturbingly blasé). My favourite piece was the first, “A Bushbaby from Harrods”: In the 1950s, the department store had a Zoo that sold exotic pets. Congo the bushbaby did his business all over her family’s flat but still was “the first great love of my life,” Blackburn insists. This was pleasant but won’t stay with me. (New purchase – remainder copy from Hay Cinema Bookshop, 2025) [86 pages] ![]()

Super-Frog Saves Tokyo by Haruki Murakami; illus. Seb Agresti and Suzanne Dean (2000, 2001; this edition 2025)

[Translated from Japanese by Jay Rubin]

This short story first appeared in English in GQ magazine in 2001 and was then included in Murakami’s collection after the quake, a response to the Kobe earthquake of 1995. “Katigiri found a giant frog waiting for him in his apartment,” it opens. The six-foot amphibian knows that an earthquake will hit Tokyo in three days’ time and wants the middle-aged banker to help him avert disaster by descending into the realm below the bank and doing battle with Worm. Legend has it that the giant worm’s anger causes natural disasters. Katigiri understandably finds it difficult to believe what’s happening, so Frog earns his trust by helping him recover a troublesome loan. Whether Frog is real or not doesn’t seem to matter; either way, imagination saves the city – and Katigiri when he has a medical crisis. I couldn’t help but think of Rachel Ingalls’ Mrs. Caliban (one of my NovNov reads last year). While this has been put together as an appealing standalone volume and was significantly more readable than any of Murakami’s recent novels that I’ve tried, I felt a bit cheated by the it-was-all-just-a-dream motif. (Public library) [86 pages]

This short story first appeared in English in GQ magazine in 2001 and was then included in Murakami’s collection after the quake, a response to the Kobe earthquake of 1995. “Katigiri found a giant frog waiting for him in his apartment,” it opens. The six-foot amphibian knows that an earthquake will hit Tokyo in three days’ time and wants the middle-aged banker to help him avert disaster by descending into the realm below the bank and doing battle with Worm. Legend has it that the giant worm’s anger causes natural disasters. Katigiri understandably finds it difficult to believe what’s happening, so Frog earns his trust by helping him recover a troublesome loan. Whether Frog is real or not doesn’t seem to matter; either way, imagination saves the city – and Katigiri when he has a medical crisis. I couldn’t help but think of Rachel Ingalls’ Mrs. Caliban (one of my NovNov reads last year). While this has been put together as an appealing standalone volume and was significantly more readable than any of Murakami’s recent novels that I’ve tried, I felt a bit cheated by the it-was-all-just-a-dream motif. (Public library) [86 pages] ![]()

Grief Is the Thing with Feathers by Max Porter (2015)

A reread – I reviewed this for Shiny New Books when it first came out and can’t better what I said then. “The novel is composed of three first-person voices: Dad, Boys (sometimes singular and sometimes plural) and Crow. The father and his two young sons are adrift in mourning; the boys’ mum died in an accident in their London flat. The three narratives resemble monologues in a play, with short lines often laid out on the page more like stanzas of a poem than prose paragraphs.” What impressed me most this time was the brilliant mash-up of allusions and genres. The title: Emily Dickinson. The central figure: Ted Hughes’s Crow. The setup: Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Raven” – while he’s grieving his lost love, a man is visited by a black bird that won’t leave until it’s delivered its message. (A raven cronked overhead as I was walking to get my cappuccino.) I was less dazzled by the actual writing, though, apart from a few very strong lines about the nature of loss, e.g. “Moving on, as a concept, is for stupid people, because any sensible person knows grief is a long-term project.” I have a feeling this would be better experienced in other media (such as audio, or the play version). I do still appreciate it as a picture of grief over time, however. Porter won the Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award as well as the Dylan Thomas Prize. (Secondhand – Gifted by a friend as part of a trip to Community Furniture Project, Newbury last year; I’d resold my original hardback copy – more fool me!) [114 pages]

A reread – I reviewed this for Shiny New Books when it first came out and can’t better what I said then. “The novel is composed of three first-person voices: Dad, Boys (sometimes singular and sometimes plural) and Crow. The father and his two young sons are adrift in mourning; the boys’ mum died in an accident in their London flat. The three narratives resemble monologues in a play, with short lines often laid out on the page more like stanzas of a poem than prose paragraphs.” What impressed me most this time was the brilliant mash-up of allusions and genres. The title: Emily Dickinson. The central figure: Ted Hughes’s Crow. The setup: Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Raven” – while he’s grieving his lost love, a man is visited by a black bird that won’t leave until it’s delivered its message. (A raven cronked overhead as I was walking to get my cappuccino.) I was less dazzled by the actual writing, though, apart from a few very strong lines about the nature of loss, e.g. “Moving on, as a concept, is for stupid people, because any sensible person knows grief is a long-term project.” I have a feeling this would be better experienced in other media (such as audio, or the play version). I do still appreciate it as a picture of grief over time, however. Porter won the Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award as well as the Dylan Thomas Prize. (Secondhand – Gifted by a friend as part of a trip to Community Furniture Project, Newbury last year; I’d resold my original hardback copy – more fool me!) [114 pages]

My original rating (in 2015): ![]()

My rating now: ![]()

Why We Hate Cheap Things by The School of Life (2017)

I’m generally a fan of the high-brow self-help books The School of Life produces, but these six micro-essays feel like cast-offs from a larger project. The title essay explores the link between the cost of an item or experience and how much we value it – with reference to pineapples and paintings. The other essays decry the fact that money doesn’t get fairly distributed, such that craftspeople and arts graduates often struggle financially when their work and minds are exactly what we should be valuing as a society. Fair enough … but any suggestions for how to fix the situation?! I’m finding Robin Wall Kimmerer’s The Serviceberry, which is also on a vaguely economic theme, much more engaging and profound. There’s no author listed for this volume, but as The School of Life is Alain de Botton’s brainchild, I’m guessing he had a hand. Perhaps he’s been cancelled? This raises a couple of interesting questions, but overall you’re probably better off spending the time with something more in depth. (Little Free Library) [78 pages]

I’m generally a fan of the high-brow self-help books The School of Life produces, but these six micro-essays feel like cast-offs from a larger project. The title essay explores the link between the cost of an item or experience and how much we value it – with reference to pineapples and paintings. The other essays decry the fact that money doesn’t get fairly distributed, such that craftspeople and arts graduates often struggle financially when their work and minds are exactly what we should be valuing as a society. Fair enough … but any suggestions for how to fix the situation?! I’m finding Robin Wall Kimmerer’s The Serviceberry, which is also on a vaguely economic theme, much more engaging and profound. There’s no author listed for this volume, but as The School of Life is Alain de Botton’s brainchild, I’m guessing he had a hand. Perhaps he’s been cancelled? This raises a couple of interesting questions, but overall you’re probably better off spending the time with something more in depth. (Little Free Library) [78 pages] ![]()

20 Books of Summer, 13–16: Tony Chan, Jen Hadfield, Kenward Anthology, Catherine Taylor

Three from my initial list (all nonfiction) and one substitute picked up at random (poetry). These are strongly place-based selections, ranging from Sheffield to Shetland and drawing on travels while also commenting on how gender and dis/ability affect daily life as well as the experience of nature.

Four Points Fourteen Lines by Tony Chan (2016)

Chan is a schoolteacher who, in 2015, left his day job to undertake a 78-day solo walk between “the four extreme cardinal points of the British mainland”: Dunnet Head (North) to Ardnamurchan Point (West) in Scotland, down to Lowestoft Ness (East) in Suffolk and across to Lizard Point, Cornwall (South). It was a solo trek of 1,400 miles. He wrote one sonnet per day, not always adhering to the same rhyme scheme but fitting his sentiments into 14 lines of standard length. He doesn’t document much practical information, but does admit he stayed in decent hotels, ate hot meals, etc. Each poem is named for the starting point and destination, but the topic might be what he sees, an experience on the road, a memory, or whatever. “Evanton to Inverness” decries a gloomy city; “Inverness to Foyers” gives thanks for his shoes and lycra undershorts. He compares Highlanders to heroic Trojans: “Something sincere in their browned, moss-green tweeds, / In their greeting voice of gentle tenor. / From ancient Hector or from ancient clans, / Here live men most earnest in words and deeds.” None of the poems are laudable in their own right, but it’s a pleasant enough project. Too often, though, Chan resorts to outmoded vocabulary to fit the form or try to prove a poetic pedigree (“Suddenly comes an Old Testament of deluge and / Tempest, deluding the sense wholly”; “I know these streets, whence they come and whither / They run”; “I learnt well some verses of Tennyson / Years ago when noble dreams were begat”) when he might have been better off varying the form and/or using free verse. (Signed copy from Little Free Library)

Chan is a schoolteacher who, in 2015, left his day job to undertake a 78-day solo walk between “the four extreme cardinal points of the British mainland”: Dunnet Head (North) to Ardnamurchan Point (West) in Scotland, down to Lowestoft Ness (East) in Suffolk and across to Lizard Point, Cornwall (South). It was a solo trek of 1,400 miles. He wrote one sonnet per day, not always adhering to the same rhyme scheme but fitting his sentiments into 14 lines of standard length. He doesn’t document much practical information, but does admit he stayed in decent hotels, ate hot meals, etc. Each poem is named for the starting point and destination, but the topic might be what he sees, an experience on the road, a memory, or whatever. “Evanton to Inverness” decries a gloomy city; “Inverness to Foyers” gives thanks for his shoes and lycra undershorts. He compares Highlanders to heroic Trojans: “Something sincere in their browned, moss-green tweeds, / In their greeting voice of gentle tenor. / From ancient Hector or from ancient clans, / Here live men most earnest in words and deeds.” None of the poems are laudable in their own right, but it’s a pleasant enough project. Too often, though, Chan resorts to outmoded vocabulary to fit the form or try to prove a poetic pedigree (“Suddenly comes an Old Testament of deluge and / Tempest, deluding the sense wholly”; “I know these streets, whence they come and whither / They run”; “I learnt well some verses of Tennyson / Years ago when noble dreams were begat”) when he might have been better off varying the form and/or using free verse. (Signed copy from Little Free Library) ![]()

Storm Pegs: A Life Made in Shetland by Jen Hadfield (2024)

This is not so much a straightforward memoir as a set of atmospheric vignettes, each headed by a relevant word or phrase in the Shaetlan dialect. Hadfield, who is British Canadian, moved to the islands in her late twenties in 2006 and soon found her niche. “My new life quickly debunked those Edge-of-the-World myths – Shetland was too busy to feel remote, and had too strong a sense of its own identity to feel frontier-like.” It’s gently ironic, she notes, that she’s a terrible sailor and gets vertigo at height yet lives somewhere with perilous cliff edges that is often reachable only by sea. Living in a trailer waiting for her home to be built on West Burra, she feels the line between indoors and out is especially thin. It’s a life of wild swimming, beachcombing, fresh fish, folk music, seabirds, kind neighbours, and good cheer that warms long winter nights. After the isolation of the pandemic period comes the unexpected joy of a partner and a pregnancy in her mid-forties. Hadfield is a Windham-Campbell Prize-winning poet, and her lyrical prose is full of lovely observations that made me hanker to return to Shetland – it’s been 19 years since my only visit, after all. This was a slow read I savoured for its language and sense of place.

This is not so much a straightforward memoir as a set of atmospheric vignettes, each headed by a relevant word or phrase in the Shaetlan dialect. Hadfield, who is British Canadian, moved to the islands in her late twenties in 2006 and soon found her niche. “My new life quickly debunked those Edge-of-the-World myths – Shetland was too busy to feel remote, and had too strong a sense of its own identity to feel frontier-like.” It’s gently ironic, she notes, that she’s a terrible sailor and gets vertigo at height yet lives somewhere with perilous cliff edges that is often reachable only by sea. Living in a trailer waiting for her home to be built on West Burra, she feels the line between indoors and out is especially thin. It’s a life of wild swimming, beachcombing, fresh fish, folk music, seabirds, kind neighbours, and good cheer that warms long winter nights. After the isolation of the pandemic period comes the unexpected joy of a partner and a pregnancy in her mid-forties. Hadfield is a Windham-Campbell Prize-winning poet, and her lyrical prose is full of lovely observations that made me hanker to return to Shetland – it’s been 19 years since my only visit, after all. This was a slow read I savoured for its language and sense of place. ![]()

With thanks to Picador for the free paperback copy for review.

From Shetland authors, I have also reviewed:

Orchid Summer by Jon Dunn (Hadfield mentions him)

Sea Bean by Sally Huband (Hadfield meets her)

The Valley at the Centre of the World by Malachy Tallack

Moving Mountains: Writing Nature through Illness and Disability, ed. Louise Kenward (2023)

I often read memoirs about chronic illness and disability – the sort of narratives recognized by the Barbellion and ACDI Literary Prizes – and the idea of nature essays that reckon with health limitations was an irresistible draw. The quality in this anthology varies widely, from excellent to barely readable (for poor prose or pretentiousness). I’ll be kind and not name names in the latter category; I’ll only say the book has been poorly served by the editing process. The best material is generally from authors with published books: Polly Atkin (Some of Us Just Fall; see also her recent response to the Raynor Winn fiasco), Victoria Bennett (All My Wild Mothers), Sally Huband (as above!), and Abi Palmer (Sanatorium). For the first three, the essay feels like an extension of their memoir, while Palmer’s inventive piece is about recreating seasons for her indoor cats. My three favourite entries, however, were Louisa Adjoa Parker’s poem “This Is Not Just Tired,” Nic Wilson’s “A Quince in the Hand” (she’s an acquaintance through New Networks for Nature and has a memoir out this summer, Land Beneath the Waves), and Eli Clare’s “Moving Close to the Ground,” about being willing to scoot and crawl to get into nature. A number of the other pieces are repetitive, overlong or poorly shaped and don’t integrate information about illness in a natural way. Kudos to Kenward for including BIPOC and trans/queer voices, though. (Christmas gift from my wish list)

I often read memoirs about chronic illness and disability – the sort of narratives recognized by the Barbellion and ACDI Literary Prizes – and the idea of nature essays that reckon with health limitations was an irresistible draw. The quality in this anthology varies widely, from excellent to barely readable (for poor prose or pretentiousness). I’ll be kind and not name names in the latter category; I’ll only say the book has been poorly served by the editing process. The best material is generally from authors with published books: Polly Atkin (Some of Us Just Fall; see also her recent response to the Raynor Winn fiasco), Victoria Bennett (All My Wild Mothers), Sally Huband (as above!), and Abi Palmer (Sanatorium). For the first three, the essay feels like an extension of their memoir, while Palmer’s inventive piece is about recreating seasons for her indoor cats. My three favourite entries, however, were Louisa Adjoa Parker’s poem “This Is Not Just Tired,” Nic Wilson’s “A Quince in the Hand” (she’s an acquaintance through New Networks for Nature and has a memoir out this summer, Land Beneath the Waves), and Eli Clare’s “Moving Close to the Ground,” about being willing to scoot and crawl to get into nature. A number of the other pieces are repetitive, overlong or poorly shaped and don’t integrate information about illness in a natural way. Kudos to Kenward for including BIPOC and trans/queer voices, though. (Christmas gift from my wish list) ![]()

The Stirrings: Coming of Age in Northern Time by Catherine Taylor (2023)

“A typical family and an ordinary story, although neither the family nor the story seems commonplace when it is your family and your story.”

Taylor, who was born in New Zealand and grew up in Sheffield, won the Ackerley Prize for this memoir. (After Dunmore and King, this is the third in my intended four-in-a-row on the 20 Books of Summer Bingo card, fulfilling the “Book published in summer” category – August 2023.) It is bookended by two pivotal summers: 1976, the last normal season in her household before her father left; and 1989, the “Second Summer of Love,” when she had an abortion (the subject of “Milk Teeth,” the best individual chapter and a strong stand-alone essay). In between, fear and outrage overshadow her life: the Yorkshire Ripper is at large, nuclear war looms, mines are closing and protesters meet with harsh reprisals, and her own health falters until she gets a diagnosis of Graves’ disease. Then, in her final year at Cardiff, one of their housemates is found dead. Taylor draws reasonably subtle links to the present day, when fascism, global threats, and femicide are, unfortunately, as timely as ever. She’s the sort of personality I see at every London literary event I attend: Wellcome Book Prize ceremonies, Weatherglass’s Future of the Novella event, and so on. I got the feeling this book is more about bearing witness to history than revealing herself, and so I never warmed to it or to her on the page. But if you’d like to get a feel for the mood of the times, or you have experience of the settings and period, you may well enjoy it more than I did. (New purchase from Bookshop.org with a Christmas book token)

Taylor, who was born in New Zealand and grew up in Sheffield, won the Ackerley Prize for this memoir. (After Dunmore and King, this is the third in my intended four-in-a-row on the 20 Books of Summer Bingo card, fulfilling the “Book published in summer” category – August 2023.) It is bookended by two pivotal summers: 1976, the last normal season in her household before her father left; and 1989, the “Second Summer of Love,” when she had an abortion (the subject of “Milk Teeth,” the best individual chapter and a strong stand-alone essay). In between, fear and outrage overshadow her life: the Yorkshire Ripper is at large, nuclear war looms, mines are closing and protesters meet with harsh reprisals, and her own health falters until she gets a diagnosis of Graves’ disease. Then, in her final year at Cardiff, one of their housemates is found dead. Taylor draws reasonably subtle links to the present day, when fascism, global threats, and femicide are, unfortunately, as timely as ever. She’s the sort of personality I see at every London literary event I attend: Wellcome Book Prize ceremonies, Weatherglass’s Future of the Novella event, and so on. I got the feeling this book is more about bearing witness to history than revealing herself, and so I never warmed to it or to her on the page. But if you’d like to get a feel for the mood of the times, or you have experience of the settings and period, you may well enjoy it more than I did. (New purchase from Bookshop.org with a Christmas book token) ![]()

Most Anticipated Books of the Second Half of 2025

My “Most Anticipated” designation sometimes seems like a kiss of death, but other times the books I choose for these lists live up to my expectations, or surpass them!

(Looking back at the 25 books I selected in January, I see that so far I have read and enjoyed 8, read but been disappointed by 4, not yet read – though they’re on my Kindle or accessible from the library – 9, and not managed to get hold of 4.)

This time around, I’ve chosen 15 books I happen to have heard about that will be released between July and December: 7 fiction and 8 nonfiction. (In release date order within genre. UK release information generally given first, if available. Note given on source if I have managed to get hold of it already.)

Fiction

The Girls Who Grew Big by Leila Mottley [10 July, Fig Tree (Penguin) / June 24, Knopf]: I was impressed with the confident voice in Mottley’s debut, Nightcrawling. She’s just 22 years old so will only keep getting better. This is “about the joys and entanglements of a fierce group of teenage mothers in a small town on the Florida panhandle. … When [16-year-old Adela] tells her parents she’s pregnant, they send her from … Indiana to her grandmother’s in Padua Beach, Florida.” I’ve read one-third so far. (Digital review copy)

The Girls Who Grew Big by Leila Mottley [10 July, Fig Tree (Penguin) / June 24, Knopf]: I was impressed with the confident voice in Mottley’s debut, Nightcrawling. She’s just 22 years old so will only keep getting better. This is “about the joys and entanglements of a fierce group of teenage mothers in a small town on the Florida panhandle. … When [16-year-old Adela] tells her parents she’s pregnant, they send her from … Indiana to her grandmother’s in Padua Beach, Florida.” I’ve read one-third so far. (Digital review copy)

Archive of Unknown Universes by Ruben Reyes Jr. [21 Aug., Footnote Press (Bonnier) / July 1, Mariner Books]: There Is a Rio Grande in Heaven was a strong speculative short story collection and I’m looking forward to his debut novel, which involves alternative history elements. (Starred Kirkus review.) “Cambridge, 2018. Ana and Luis’s relationship is on the rocks, despite their many similarities, including … mothers who both fled El Salvador during the war. In her search for answers, and against her best judgement, Ana uses The Defractor, an experimental device that allows users to peek into alternate versions of their lives.”

Archive of Unknown Universes by Ruben Reyes Jr. [21 Aug., Footnote Press (Bonnier) / July 1, Mariner Books]: There Is a Rio Grande in Heaven was a strong speculative short story collection and I’m looking forward to his debut novel, which involves alternative history elements. (Starred Kirkus review.) “Cambridge, 2018. Ana and Luis’s relationship is on the rocks, despite their many similarities, including … mothers who both fled El Salvador during the war. In her search for answers, and against her best judgement, Ana uses The Defractor, an experimental device that allows users to peek into alternate versions of their lives.”

Minor Black Figures by Brandon Taylor [Oct. 7, Riverhead / 5 March 2026, Jonathan Cape (Penguin)]: I’ve read all of his works … but I’m so glad he’s moving past campus settings now. “A newcomer to New York, Wyeth is a Black painter who grew up in the South and is trying to find his place in the contemporary Manhattan art scene. … When he meets Keating, a white former seminarian who left the priesthood, Wyeth begins to reconsider how to observe the world, in the process facing questions about the conflicts between Black and white art, the white gaze on the Black body, and the compromises we make – in art and in life.” (Edelweiss download)

Minor Black Figures by Brandon Taylor [Oct. 7, Riverhead / 5 March 2026, Jonathan Cape (Penguin)]: I’ve read all of his works … but I’m so glad he’s moving past campus settings now. “A newcomer to New York, Wyeth is a Black painter who grew up in the South and is trying to find his place in the contemporary Manhattan art scene. … When he meets Keating, a white former seminarian who left the priesthood, Wyeth begins to reconsider how to observe the world, in the process facing questions about the conflicts between Black and white art, the white gaze on the Black body, and the compromises we make – in art and in life.” (Edelweiss download)

Heart the Lover by Lily King [16 Oct., Canongate / Oct. 7, Grove Press]: I’ve read several of her books and after Writers & Lovers I’m a forever fan. “In the fall of her senior year of college, [Jordan] meets two star students from her 17th-Century Lit class, Sam and Yash. … she quickly discovers the pleasures of friendship, love and her own intellectual ambition. … when a surprise visit and unexpected news brings the past crashing into the present, Jordan returns to a world she left behind and is forced to confront the decisions and deceptions of her younger self.” (Edelweiss download)

Heart the Lover by Lily King [16 Oct., Canongate / Oct. 7, Grove Press]: I’ve read several of her books and after Writers & Lovers I’m a forever fan. “In the fall of her senior year of college, [Jordan] meets two star students from her 17th-Century Lit class, Sam and Yash. … she quickly discovers the pleasures of friendship, love and her own intellectual ambition. … when a surprise visit and unexpected news brings the past crashing into the present, Jordan returns to a world she left behind and is forced to confront the decisions and deceptions of her younger self.” (Edelweiss download)

Wreck by Catherine Newman [28 Oct., Transworld / Harper]: This is a sequel to Sandwich, and in general sequels should not exist. However, I can make a rare exception. Set two years on, this finds “Rocky, still anxious, nostalgic, and funny, obsessed with a local accident that only tangentially affects them—and with a medical condition that, she hopes, won’t affect them at all.” In a recent Substack post, Newman compared it to Small Rain, my book of 2024, for the focus on a mystery medical condition. (Edelweiss download)

Wreck by Catherine Newman [28 Oct., Transworld / Harper]: This is a sequel to Sandwich, and in general sequels should not exist. However, I can make a rare exception. Set two years on, this finds “Rocky, still anxious, nostalgic, and funny, obsessed with a local accident that only tangentially affects them—and with a medical condition that, she hopes, won’t affect them at all.” In a recent Substack post, Newman compared it to Small Rain, my book of 2024, for the focus on a mystery medical condition. (Edelweiss download)

Palaver by Bryan Washington [Nov. 4, Farrar, Straus, and Giroux / 1 Jan. 2026, Atlantic]: I’ve read all his work and I’m definitely a fan, though I wish that (like Taylor previously) he wouldn’t keep combining the same elements each time. I’ll be reviewing this early for Shelf Awareness; hooray that I don’t have to wait until 2026! “He’s entangled in a sexual relationship with a married man, and while he has built a chosen family in Japan, he is estranged from his family in Houston, particularly his mother … Then, in the weeks leading up to Christmas, ten years since they’ve last seen each other, the mother arrives uninvited on his doorstep. Separated only by the son’s cat, Taro, the two of them bristle against each other immediately.” (Edelweiss download)

Palaver by Bryan Washington [Nov. 4, Farrar, Straus, and Giroux / 1 Jan. 2026, Atlantic]: I’ve read all his work and I’m definitely a fan, though I wish that (like Taylor previously) he wouldn’t keep combining the same elements each time. I’ll be reviewing this early for Shelf Awareness; hooray that I don’t have to wait until 2026! “He’s entangled in a sexual relationship with a married man, and while he has built a chosen family in Japan, he is estranged from his family in Houston, particularly his mother … Then, in the weeks leading up to Christmas, ten years since they’ve last seen each other, the mother arrives uninvited on his doorstep. Separated only by the son’s cat, Taro, the two of them bristle against each other immediately.” (Edelweiss download)

The Silver Book by Olivia Laing [6 Nov., Hamish Hamilton (Penguin) / 11 Nov., Farrar, Straus and Giroux]: I’ve read all but one of Laing’s books and consider her one of our most important contemporary thinkers. I was also pleasantly surprised by Crudo so will be reading this second novel, too. I’ll be reviewing it early for Shelf Awareness as well. “September 1974. Two men meet by chance in Venice. One is a young English artist, in panicked flight from London. The other is Danilo Donati, the magician of Italian cinema. … The Silver Book is at once a queer love story and a noirish thriller, set in the dream factory of cinema. (Edelweiss download)

The Silver Book by Olivia Laing [6 Nov., Hamish Hamilton (Penguin) / 11 Nov., Farrar, Straus and Giroux]: I’ve read all but one of Laing’s books and consider her one of our most important contemporary thinkers. I was also pleasantly surprised by Crudo so will be reading this second novel, too. I’ll be reviewing it early for Shelf Awareness as well. “September 1974. Two men meet by chance in Venice. One is a young English artist, in panicked flight from London. The other is Danilo Donati, the magician of Italian cinema. … The Silver Book is at once a queer love story and a noirish thriller, set in the dream factory of cinema. (Edelweiss download)

Nonfiction

Jesusland: Stories from the Upside[-]Down World of Christian Pop Culture by Joelle Kidd [Aug. 12, ECW]: “Through nine incisive, honest, and emotional essays, Jesusland exposes the pop cultural machinations of evangelicalism, while giving voice to aughts-era Christian children and teens who are now adults looking back at their time measuring the length of their skirts … exploring the pop culture that both reflected and shaped an entire generation of young people.” Yep, that includes me! Looking forward to a mixture of Y2K and Jesus Freak. (NetGalley download)

Jesusland: Stories from the Upside[-]Down World of Christian Pop Culture by Joelle Kidd [Aug. 12, ECW]: “Through nine incisive, honest, and emotional essays, Jesusland exposes the pop cultural machinations of evangelicalism, while giving voice to aughts-era Christian children and teens who are now adults looking back at their time measuring the length of their skirts … exploring the pop culture that both reflected and shaped an entire generation of young people.” Yep, that includes me! Looking forward to a mixture of Y2K and Jesus Freak. (NetGalley download)

Somebody Is Walking on Your Grave: My Cemetery Journeys by Mariana Enríquez; translated from Spanish by Megan McDowell [25 Sept., Granta / Sept. 30, Hogarth]: I’ve enjoyed her creepy short stories, plus I love touring graveyards. “In 2013, when the body of a friend’s mother who was disappeared during Argentina’s military dictatorship was found in a common grave, she began to examine more deeply the complex meanings of cemeteries and where our bodies come to rest. In this vivid, cinematic book … Enriquez travels North and South America, Europe and Australia … [and] investigates each cemetery’s history, architecture, its dead (famous and not), its saints and ghosts, its caretakers and visitors.” (Edelweiss download, for Shelf Awareness review)

Somebody Is Walking on Your Grave: My Cemetery Journeys by Mariana Enríquez; translated from Spanish by Megan McDowell [25 Sept., Granta / Sept. 30, Hogarth]: I’ve enjoyed her creepy short stories, plus I love touring graveyards. “In 2013, when the body of a friend’s mother who was disappeared during Argentina’s military dictatorship was found in a common grave, she began to examine more deeply the complex meanings of cemeteries and where our bodies come to rest. In this vivid, cinematic book … Enriquez travels North and South America, Europe and Australia … [and] investigates each cemetery’s history, architecture, its dead (famous and not), its saints and ghosts, its caretakers and visitors.” (Edelweiss download, for Shelf Awareness review)

Ghosts of the Farm: Two Women’s Journeys Through Time, Land and Community by Nicola Chester [30 Sept., Chelsea Green]: Nicola is our local nature writer and is so wise on class and countryside matters. On Gallows Down was her wonderful debut and, though I know very little about it, I’m looking forward to her second book. “This is the story of Miss White, a woman who lived in the author’s village 80 years ago, a pioneer who realised her ambition to become a farmer during the Second World War. … Moving between Nicola’s own attempts to work outdoors and Miss White’s desire to farm a generation earlier, Nicola explores the parallels between their lives – and the differences.”

Ghosts of the Farm: Two Women’s Journeys Through Time, Land and Community by Nicola Chester [30 Sept., Chelsea Green]: Nicola is our local nature writer and is so wise on class and countryside matters. On Gallows Down was her wonderful debut and, though I know very little about it, I’m looking forward to her second book. “This is the story of Miss White, a woman who lived in the author’s village 80 years ago, a pioneer who realised her ambition to become a farmer during the Second World War. … Moving between Nicola’s own attempts to work outdoors and Miss White’s desire to farm a generation earlier, Nicola explores the parallels between their lives – and the differences.”

Death of an Ordinary Man by Sarah Perry [2 Oct., Vintage (Penguin)]: I’ve had a very mixed experience with Perry’s fiction, but a short bereavement memoir should be right up my street. “Sarah Perry’s father-in-law, David, died at home nine days after a cancer diagnosis and having previously been in the good health. The speed of his illness outstripped that of the NHS and social care, so the majority of nursing fell to Sarah and her husband. They witnessed what happens to the body and spirit, hour by hour, as it approaches death.”

Death of an Ordinary Man by Sarah Perry [2 Oct., Vintage (Penguin)]: I’ve had a very mixed experience with Perry’s fiction, but a short bereavement memoir should be right up my street. “Sarah Perry’s father-in-law, David, died at home nine days after a cancer diagnosis and having previously been in the good health. The speed of his illness outstripped that of the NHS and social care, so the majority of nursing fell to Sarah and her husband. They witnessed what happens to the body and spirit, hour by hour, as it approaches death.”

Book of Lives: A Memoir of Sorts by Margaret Atwood [4 Nov., Vintage (Penguin) / Doubleday]: It’s Atwood; ’nuff said, though I admit I’m daunted by the page count. “Raised by ruggedly independent, scientifically minded parents – entomologist father, dietician mother – Atwood spent most of each year in the wild forest of northern Quebec. … [She links] seminal moments to the books that have shaped our literary landscape. … In pages bursting with bohemian gatherings … and major political turning points, we meet poets, bears, Hollywood actors and larger-than-life characters straight from the pages of an Atwood novel.”

Book of Lives: A Memoir of Sorts by Margaret Atwood [4 Nov., Vintage (Penguin) / Doubleday]: It’s Atwood; ’nuff said, though I admit I’m daunted by the page count. “Raised by ruggedly independent, scientifically minded parents – entomologist father, dietician mother – Atwood spent most of each year in the wild forest of northern Quebec. … [She links] seminal moments to the books that have shaped our literary landscape. … In pages bursting with bohemian gatherings … and major political turning points, we meet poets, bears, Hollywood actors and larger-than-life characters straight from the pages of an Atwood novel.”

Tigers Between Empires: The Improbable Return of Great Cats to the Forests of Russia and China by Jonathan C. Slaght [4 Nov., Allen Lane / Farrar, Straus and Giroux]: Slaght’s Owls of the Eastern Ice was one of the best books I read in 2022; he’s a top-notch nature and travel writer with an environmentalist’s conscience. After the fall of the Soviet Union, “scientists came together to found the Siberian Tiger Project[, which …] captured and released more than 114 tigers over three decades. … [C]haracters, both feline and human, come fully alive as we travel with them through the quiet and changing forests of Amur.” (NetGalley download)

Tigers Between Empires: The Improbable Return of Great Cats to the Forests of Russia and China by Jonathan C. Slaght [4 Nov., Allen Lane / Farrar, Straus and Giroux]: Slaght’s Owls of the Eastern Ice was one of the best books I read in 2022; he’s a top-notch nature and travel writer with an environmentalist’s conscience. After the fall of the Soviet Union, “scientists came together to found the Siberian Tiger Project[, which …] captured and released more than 114 tigers over three decades. … [C]haracters, both feline and human, come fully alive as we travel with them through the quiet and changing forests of Amur.” (NetGalley download)

Joyride by Susan Orlean [6 Nov., Atlantic Books / Oct. 14, Avid Reader Press (Simon & Schuster)]: I’m a fan of Orlean’s genre-busting nonfiction, e.g. The Orchid Thief and The Library Book, and have always wanted to try more by her. “Joyride is her most personal book ever—a searching journey through finding her feet as a journalist, recovering from the excruciating collapse of her first marriage, falling head-over-heels in love again, becoming a mother while mourning the decline of her own mother, sojourning to Hollywood for films based on her work. … Joyride is also a time machine to a bygone era of journalism.”

Joyride by Susan Orlean [6 Nov., Atlantic Books / Oct. 14, Avid Reader Press (Simon & Schuster)]: I’m a fan of Orlean’s genre-busting nonfiction, e.g. The Orchid Thief and The Library Book, and have always wanted to try more by her. “Joyride is her most personal book ever—a searching journey through finding her feet as a journalist, recovering from the excruciating collapse of her first marriage, falling head-over-heels in love again, becoming a mother while mourning the decline of her own mother, sojourning to Hollywood for films based on her work. … Joyride is also a time machine to a bygone era of journalism.”

A Long Game: Notes on Writing Fiction by Elizabeth McCracken [Dec. 2, Ecco]: I’m not big on craft books, but will occasionally read one by an author I admire; McCracken won my heart with The Hero of This Book. “How does one face the blank page? Move a character around a room? Deal with time? Undertake revision? The good and bad news is that in fiction writing, there are no definitive answers. … McCracken … has been teaching for more than thirty-five years [… and] shares insights gleaned along the way, offering practical tips and incisive thoughts about her own work as an artist.” (Edelweiss download)

A Long Game: Notes on Writing Fiction by Elizabeth McCracken [Dec. 2, Ecco]: I’m not big on craft books, but will occasionally read one by an author I admire; McCracken won my heart with The Hero of This Book. “How does one face the blank page? Move a character around a room? Deal with time? Undertake revision? The good and bad news is that in fiction writing, there are no definitive answers. … McCracken … has been teaching for more than thirty-five years [… and] shares insights gleaned along the way, offering practical tips and incisive thoughts about her own work as an artist.” (Edelweiss download)

As a bonus, here are two advanced releases that I reviewed early:

Trying: A Memoir by Chloe Caldwell [Aug. 5, Graywolf] (Reviewed for Foreword): Caldwell devoted much of her thirties to trying to get pregnant via intrauterine insemination. She developed rituals to ease the grueling routine: After every visit, she made a stop for luxury foodstuffs and beauty products. But then her marriage imploded. When she began dating women and her determination to become a mother persisted, a new conception strategy was needed. The book’s fragmentary style suits its aura of uncertainty about the future. Sparse pages host a few sentences or paragraphs, interspersed with wry lists.

Trying: A Memoir by Chloe Caldwell [Aug. 5, Graywolf] (Reviewed for Foreword): Caldwell devoted much of her thirties to trying to get pregnant via intrauterine insemination. She developed rituals to ease the grueling routine: After every visit, she made a stop for luxury foodstuffs and beauty products. But then her marriage imploded. When she began dating women and her determination to become a mother persisted, a new conception strategy was needed. The book’s fragmentary style suits its aura of uncertainty about the future. Sparse pages host a few sentences or paragraphs, interspersed with wry lists. ![]()

If You Love It, Let It Kill You by Hannah Pittard [July 15, Henry Holt] (Reviewed for Shelf Awareness): A quirky work of autofiction about an author/professor tested by her ex-husband’s success, her codependent family, and an encounter with a talking cat. Hana P. (or should that be Pittard?) relishes flouting the “rules” of creative writing. With her affectations and unreliability, she can be a frustrating narrator, but the metafictional angle renders her more wily than precious. The dialogue and scenes sparkle, and there are delightful characters This gleefully odd book is perfect for Miranda July and Patricia Lockwood fans.

If You Love It, Let It Kill You by Hannah Pittard [July 15, Henry Holt] (Reviewed for Shelf Awareness): A quirky work of autofiction about an author/professor tested by her ex-husband’s success, her codependent family, and an encounter with a talking cat. Hana P. (or should that be Pittard?) relishes flouting the “rules” of creative writing. With her affectations and unreliability, she can be a frustrating narrator, but the metafictional angle renders her more wily than precious. The dialogue and scenes sparkle, and there are delightful characters This gleefully odd book is perfect for Miranda July and Patricia Lockwood fans. ![]()

I can also recommend:

Both/And: Essays by Trans and Gender-Nonconforming Writers of Color, ed. Denne Michele Norris [Aug. 12, HarperOne / 25 Sept., HarperCollins] (Review to come for Shelf Awareness) ![]()

Other People’s Mothers by Julie Marie Wade [Sept. 2, Univ. of Florida Press] (Review pending for Foreword) ![]()

Which of these catch your eye? Any other books you’re looking forward to in this second half of the year?

Queer people of all varieties have always been with us; they just might have understood their experience or talked about it in different terms. So while Combs and Eakett are careful not to apply labels retrospectively, they feature a plethora of people who lived as a different gender to that assigned at birth. Apart from a few familiar names like Lili Elbe and Marsha P. Johnson, most were new to me. For every heartening story of an emperor, monk or explorer who managed to live out their true identity in peace, there are three distressing ones of those forced to conform. Many Indigenous cultures held a special place for gender-nonconforming individuals; colonizers would have seen this as evidence of desperate need of civilizing. Even doctors who were willing to help with early medical transitions retained primitive ideas about gender and its connection to genitals. The structure is chronological, with a single colour per chapter. Panes reenact scenes and feature talking heads explaining historical developments and critical theory. A final section is devoted to modern-day heroes campaigning for trans rights and seeking to preserve an archive of queer history. This was a little didactic, but ideal for teens, I think, and certainly not just one for gender studies students.

Queer people of all varieties have always been with us; they just might have understood their experience or talked about it in different terms. So while Combs and Eakett are careful not to apply labels retrospectively, they feature a plethora of people who lived as a different gender to that assigned at birth. Apart from a few familiar names like Lili Elbe and Marsha P. Johnson, most were new to me. For every heartening story of an emperor, monk or explorer who managed to live out their true identity in peace, there are three distressing ones of those forced to conform. Many Indigenous cultures held a special place for gender-nonconforming individuals; colonizers would have seen this as evidence of desperate need of civilizing. Even doctors who were willing to help with early medical transitions retained primitive ideas about gender and its connection to genitals. The structure is chronological, with a single colour per chapter. Panes reenact scenes and feature talking heads explaining historical developments and critical theory. A final section is devoted to modern-day heroes campaigning for trans rights and seeking to preserve an archive of queer history. This was a little didactic, but ideal for teens, I think, and certainly not just one for gender studies students.

File this with other surprising nonfiction books by well-known novelists. In 2015, Grenville started struggling while on a book tour: everything from a taxi’s air freshener and a hotel’s cleaning products to a fellow passenger’s perfume was giving her headaches. She felt like a diva for stipulating she couldn’t be around fragrances, but as she started looking into it she realized she wasn’t alone. I thought this was just going to be about perfume, but it covers all fragranced products, which can list “parfum” on their ingredients without specifying what that is – trade secrets. The problem is, fragrances contain any of thousands of synthetic chemicals, most of which have never been tested and thus are unregulated. Even those found to be carcinogens or endocrine disruptors in rodent studies might be approved for humans because it’s not taken into account how these products are actually used. Prolonged or repeat contact has cumulative effects. The synthetic musks in toiletries and laundry detergents are particularly bad, acting as estrogen mimics and likely associated with prostate and breast cancer. I tend to buy whatever’s on offer in Boots, but as soon as my Herbal Essences bottle is empty I’m going back to Faith in Nature (look for plant extracts). The science at the core of the book is a little repetitive, but eased by the social chapters to either side, and you can tell from the footnotes that Grenville really did her research.