Three on a Theme: Christmas Novellas I (Re-)Read This Year

I wasn’t sure I’d manage any holiday-appropriate reading this year, but thanks to their novella length I actually finished three, two in advance and one in a single sitting on the day itself. Two of these happen to be in translation: little slices of continental Christmas.

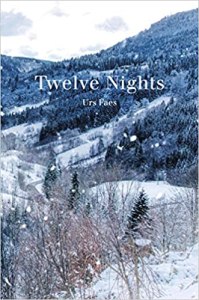

Twelve Nights by Urs Faes (2018; 2020)

[Translated from the German by Jamie Lee Searle]

In this Swiss novella, the Twelve Nights between Christmas and Epiphany are a time of mischief when good folk have to protect themselves from the tricks of evil spirits. Manfred has trekked back to his home valley hoping to make things right with his brother, Sebastian. They have been estranged for several decades – since Sebastian unexpectedly inherited the family farm and stole Manfred’s sweetheart, Minna. These perceived betrayals were met with a vengeful act of cruelty (but why oh why did it have to be against an animal?). At a snow-surrounded inn, Manfred convalesces and tries to summon the courage to show up at Sebastian’s door. At only 84 small-format pages, this is more of a short story. The setting and spare writing are appealing, as is the prospect of grace extended. But this was over before it began; it didn’t feel worth what I paid. Perhaps I would have been happier to encounter it in an anthology or a longer collection of Faes’s short fiction. (Secondhand – Hungerford Bookshop)

In this Swiss novella, the Twelve Nights between Christmas and Epiphany are a time of mischief when good folk have to protect themselves from the tricks of evil spirits. Manfred has trekked back to his home valley hoping to make things right with his brother, Sebastian. They have been estranged for several decades – since Sebastian unexpectedly inherited the family farm and stole Manfred’s sweetheart, Minna. These perceived betrayals were met with a vengeful act of cruelty (but why oh why did it have to be against an animal?). At a snow-surrounded inn, Manfred convalesces and tries to summon the courage to show up at Sebastian’s door. At only 84 small-format pages, this is more of a short story. The setting and spare writing are appealing, as is the prospect of grace extended. But this was over before it began; it didn’t feel worth what I paid. Perhaps I would have been happier to encounter it in an anthology or a longer collection of Faes’s short fiction. (Secondhand – Hungerford Bookshop) ![]()

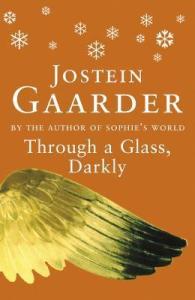

Through a Glass, Darkly by Jostein Gaarder (1993; 1998)

[Translated from the Norwegian by Elizabeth Rokkan]

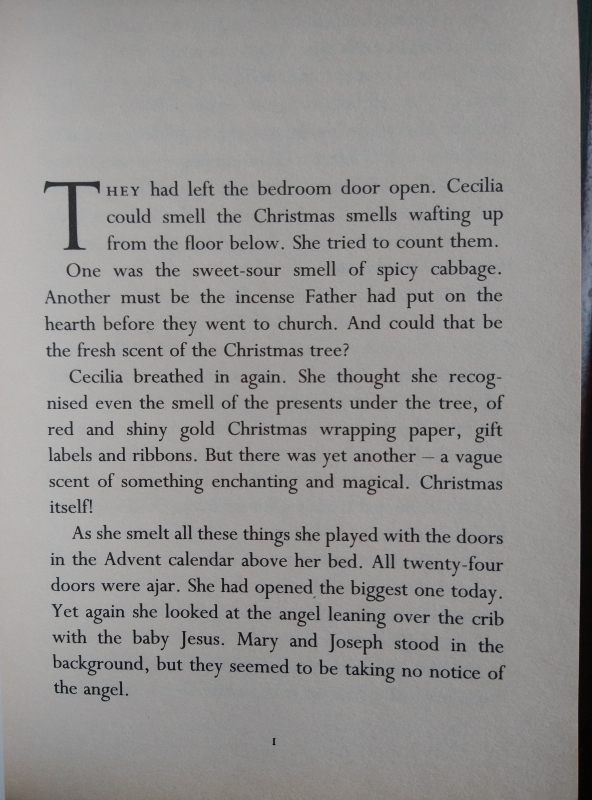

On Christmas Day, Cecilia is mostly confined to bed, yet the preteen experiences the holiday through the sounds and smells of what’s happening downstairs. (What a cosy first page!)

Her father later carries her down to open her presents: skis, a toboggan, skates – her family has given her all she asked for even though everyone knows she won’t be doing sport again; there is no further treatment for her terminal cancer. That night, the angel Ariel appears to Cecilia and gets her thinking about the mysteries of life. He’s fascinated by memory and the temporary loss of consciousness that is sleep. How do these human processes work? “I wish I’d thought more about how it is to live,” Cecilia sighs, to which Ariel replies, “It’s never too late.” Weeks pass and Ariel engages Cecilia in dialogues and takes her on middle-of-the-night outdoor adventures, always getting her back before her parents get up to check on her. The book emphasizes the wonder of being alive: “You are an animal with the soul of an angel, Cecilia. In that way you’ve been given the best of both worlds.” This is very much a YA book and a little saccharine for me, but at least it was only 161 pages rather than the nearly 400 of Sophie’s World. (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project, Newbury)

Her father later carries her down to open her presents: skis, a toboggan, skates – her family has given her all she asked for even though everyone knows she won’t be doing sport again; there is no further treatment for her terminal cancer. That night, the angel Ariel appears to Cecilia and gets her thinking about the mysteries of life. He’s fascinated by memory and the temporary loss of consciousness that is sleep. How do these human processes work? “I wish I’d thought more about how it is to live,” Cecilia sighs, to which Ariel replies, “It’s never too late.” Weeks pass and Ariel engages Cecilia in dialogues and takes her on middle-of-the-night outdoor adventures, always getting her back before her parents get up to check on her. The book emphasizes the wonder of being alive: “You are an animal with the soul of an angel, Cecilia. In that way you’ve been given the best of both worlds.” This is very much a YA book and a little saccharine for me, but at least it was only 161 pages rather than the nearly 400 of Sophie’s World. (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project, Newbury) ![]()

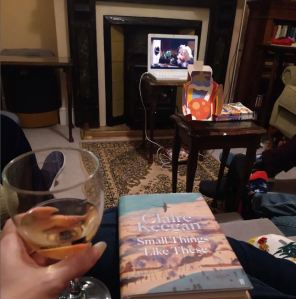

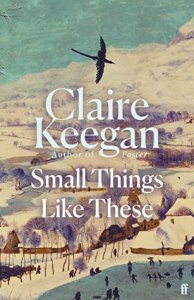

Small Things Like These by Claire Keegan (2021)

I idly reread this while The Muppet Christmas Carol played in the background on a lazy, overfed Christmas evening.

It was an odd experience: having seen the big-screen adaptation just last month, the blow-by-blow was overly familiar to me and I saw Cillian Murphy and Emily Watson, if not the minor actors, in my mind’s eye. I realized fully just how faithful the screenplay is to the book. The film enhances not just the atmosphere but also the plot through the visuals. It takes what was so subtle in the book – blink-and-you’ll-miss-it – and makes it more obvious. Normally I might think it a shame to undermine the nuance, but in this case I was glad of it. Bill Furlong’s midlife angst and emotional journey, in particular, are emphasized in the film. It was probably a mistake to read this a third time within so short a span of time; it often takes me more like 5–10 years to appreciate a book anew. So I was back to my ‘nice little story’ reaction this time, but would still recommend this to you – book or film – if you haven’t yet experienced it. (Free at a West Berkshire Council recycling event)

It was an odd experience: having seen the big-screen adaptation just last month, the blow-by-blow was overly familiar to me and I saw Cillian Murphy and Emily Watson, if not the minor actors, in my mind’s eye. I realized fully just how faithful the screenplay is to the book. The film enhances not just the atmosphere but also the plot through the visuals. It takes what was so subtle in the book – blink-and-you’ll-miss-it – and makes it more obvious. Normally I might think it a shame to undermine the nuance, but in this case I was glad of it. Bill Furlong’s midlife angst and emotional journey, in particular, are emphasized in the film. It was probably a mistake to read this a third time within so short a span of time; it often takes me more like 5–10 years to appreciate a book anew. So I was back to my ‘nice little story’ reaction this time, but would still recommend this to you – book or film – if you haven’t yet experienced it. (Free at a West Berkshire Council recycling event)

Previous ratings: ![]() (2021 review);

(2021 review); ![]() (2022 review)

(2022 review)

My rating this time: ![]()

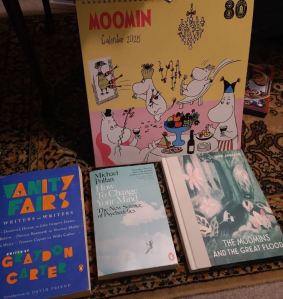

We hosted family for Christmas for the first time, which truly made me feel like a proper grown-up. It was stressful and chaotic but lovely and over all too soon. Here’s my lil’ book haul (but there was also a £50 book token, so I will buy many more!).

I hope everyone has been enjoying the holidays. I have various year-end posts in progress but of course the final Best-of list and statistics will have to wait until the turning of the year.

Coming up:

Sunday 29th: Best Backlist Reads of the Year

Monday 30th: Love Your Library & 2024 Reading Superlatives

Tuesday 31st: Best Books of 2024

Wednesday 1st: Final statistics on 2024’s reading

Recommended April Releases by Amy Bloom, Sarah Manguso & Sara Rauch

Just two weeks until moving day – we’ve got a long weekend ahead of us of sanding, painting, packing and gardening. As busy as I am with house stuff, I’m endeavouring to keep up with the new releases publishers have been so good as to send me. Today I review three short works: the story of accompanying a beloved husband to Switzerland for an assisted suicide, a coolly perceptive novella of American girlhood, and a vivid memoir of two momentous relationships. (April was a big month for new books: I have another 6–8 on the go that I’ll be catching up on in the future.) All:

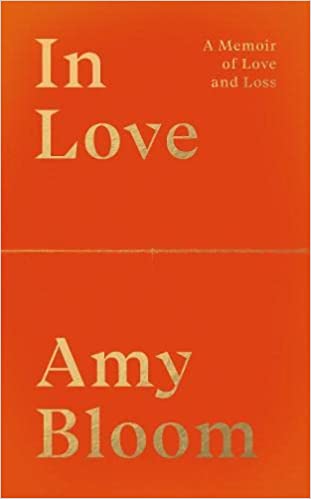

In Love: A Memoir of Love and Loss by Amy Bloom

“We’re not here for a long time, we’re here for a good time.”

(Ameche family saying)

Given the psychological astuteness of her fiction, it’s no surprise that Bloom is a practicing psychotherapist. She treats her own life with the same compassionate understanding, and even though the main events covered in this brilliantly understated memoir only occurred two and a bit years ago, she has remarkable perspective and avoids self-pity and mawkishness. Her husband, Brian Ameche, was diagnosed with early-onset Alzheimer’s in his mid-60s, having exhibited mild cognitive impairment for several years. Brian quickly resolved to make a dignified exit while he still, mostly, had his faculties. But he needed Bloom’s help.

“I worry, sometimes, that a better wife, certainly a different wife, would have said no, would have insisted on keeping her husband in this world until his body gave out. It seems to me that I’m doing the right thing, in supporting Brian in his decision, but it would feel better and easier if he could make all the arrangements himself and I could just be a dutiful duckling, following in his wake. Of course, if he could make all the arrangements himself, he wouldn’t have Alzheimer’s”

U.S. cover

She achieves the perfect tone, mixing black humour with teeth-gritted practicality. Research into acquiring sodium pentobarbital via doctor friends soon hit a dead end and they settled instead on flying to Switzerland for an assisted suicide through Dignitas – a proven but bureaucracy-ridden and expensive method. The first quarter of the book is a day-by-day diary of their January 2020 trip to Zurich as they perform the farce of a couple on vacation. A long central section surveys their relationship – a second chance for both of them in midlife – and how Brian, a strapping Yale sportsman and accomplished architect, gradually descended into confusion and dependence. The assisted suicide itself, and the aftermath as she returns to the USA and organizes a memorial service, fill a matter-of-fact 20 pages towards the close.

Hard as parts of this are to read, there are so many lovely moments of kindness (the letter her psychotherapist writes about Brian’s condition to clinch their place at Dignitas!) and laughter, despite it all (Brian’s endless fishing stories!). While Bloom doesn’t spare herself here, diligently documenting times when she was impatient and petty, she doesn’t come across as impossibly brave or stoic. She was just doing what she felt she had to, to show her love for Brian, and weeping all the way. An essential, compelling read.

With thanks to Granta for the free copy for review.

Very Cold People by Sarah Manguso

I’ve read Manguso’s four nonfiction works and especially love her Wellcome Book Prize-shortlisted medical memoir The Two Kinds of Decay. The aphoristic style she developed in her two previous books continues here as discrete paragraphs and brief vignettes build to a gloomy portrait of Ruthie’s archetypical affection-starved childhood in the fictional Massachusetts town of Waitsfield in the 1980s and 90s. She’s an only child whose parents no doubt were doing their best after emotionally stunted upbringings but never managed to make her feel unconditionally loved. Praise is always qualified and stingily administered. Ruthie feels like a burden and escapes into her imaginings of how local Brahmins – Cabots and Emersons and Lowells – lived. Her family is cash-poor compared to their neighbours and loves nothing more than a trip to the dump: “My parents weren’t after shiny things or even beautiful things; they simply liked getting things that stupid people threw away.”

The depiction of Ruthie’s narcissistic mother is especially acute. She has to make everything about her; any minor success of her daughter’s is a blow to her own ego. I marked out an excruciating passage that made me feel so sorry for this character. A European friend of the family visits and Ruthie’s mother serves corn muffins that he seems to appreciate.

My mother brought up her triumph for years. … She’d believed his praise was genuine. She hadn’t noticed that he’d pegged her as a person who would snatch up any compliment into the maw of her unloved, throbbing little heart.

U.S. cover

At school, as in her home life, Ruthie dissociates herself from every potentially traumatic situation. “My life felt unreal and I felt half-invested. I felt indistinct, like someone else’s dream.” Her friend circle is an abbreviated A–Z of girlhood: Amber, Bee, Charlie and Colleen. “Odd” men – meaning sexual predators – seem to be everywhere and these adolescent girls are horribly vulnerable. Molestation is such an open secret in the world of the novel that Ruthie assumes this is why her mother is the way she is.

While the #MeToo theme didn’t resonate with me personally, so much else did. Chemistry class, sleepovers, getting one’s first period, falling off a bike: this is the stuff of girlhood – if not universally, then certainly for the (largely pre-tech) American 1990s as I experienced them. I found myself inhabiting memories I hadn’t revisited for years, and a thought came that had perhaps never occurred to me before: for our time and area, my family was poor, too. I’m grateful for my ignorance: what scarred Ruthie passed me by; I was a purely happy child. But I think my sister, born seven years earlier, suffered more, in ways that she’d recognize here. This has something of the flavour of Eileen and My Name Is Lucy Barton and reads like autofiction even though it’s not presented as such. The style and contents may well be divisive. I’ll be curious to hear if other readers see themselves in its sketches of childhood.

With thanks to Picador for the proof copy for review.

XO by Sara Rauch

Sara Rauch won the Electric Book Award for her short story collection What Shines from It. This compact autobiographical parcel focuses on a point in her early thirties when she lived with a long-time female partner, “Piper”, and had an intense affair with “Liam”, a fellow writer she met at a residency.

“no one sets out in search of buried treasure when they’re content with life as it is”

“Longing isn’t cheating (of this I was certain), even when it brushes its whiskers against your cheek.”

Adultery is among the most ancient human stories we have, a fact Rauch acknowledges by braiding through the narrative her musings on religion and storytelling by way of her Catholic upbringing and interest in myths and fairy tales. She’s looking for the patterns of her own experience and how endings make way for new life. The title has multiple meanings: embraces, crossroads and coming full circle. Like a spider’s web, her narrative pulls in many threads to make an ordered whole. All through, bisexuality is a baseline, not something that needs to be interrogated.

Adultery is among the most ancient human stories we have, a fact Rauch acknowledges by braiding through the narrative her musings on religion and storytelling by way of her Catholic upbringing and interest in myths and fairy tales. She’s looking for the patterns of her own experience and how endings make way for new life. The title has multiple meanings: embraces, crossroads and coming full circle. Like a spider’s web, her narrative pulls in many threads to make an ordered whole. All through, bisexuality is a baseline, not something that needs to be interrogated.

This reminded me of a number of books I’ve read about short-lived affairs – Tides, The Instant – and about renegotiating relationships in a queer life – The Fixed Stars, In the Dream House – but felt most like reading a May Sarton journal for how intimately it recreates daily routines of writing, cooking, caring for cats, and weighing up past, present and future. Lovely stuff.

With thanks to publicist Lori Hettler and Autofocus Books for the e-copy for review.

Will you seek out one or more of these books?

What other April releases can you recommend?

Reading Robertson Davies Week: Fifth Business

I’m grateful to Lory (of The Emerald City Book Review) for hosting this past week’s Robertson Davies readalong, which was my excuse to finally try him for the first time. Of course, Canadians have long recognized what a treasure he is, but he’s less known elsewhere. I do remember that Erica Wagner, one of my literary heroes (an American in England; former books editor of the London Times, etc.), has expressed great admiration for his work.

I started with what I had to hand: Fifth Business (1970), the first volume of The Deptford Trilogy. In the theatre world, the title phrase refers to a bit player who yet has importance to the outcome of a drama, and that’s how the narrator, Dunstan Ramsay, thinks of himself. I was reminded right away of the opening of Charles Dickens’s David Copperfield: “Whether I shall turn out to be the hero of my own life, or whether that station will be held by anybody else, these pages must show.” In the first line Ramsay introduces himself in relation to another person: “My lifelong involvement with Mrs. Dempster began at 5.58 o’clock p.m. on 27 December 1908, at which time I was ten years and seven months old.”

Specifically, he dodged a snowball meant for him – thrown by his frenemy, Percy Boyd Staunton – and it hit Mrs. Dempster, wife of the local Baptist minister, in the back of the head, knocking her over and 1) sending her into early labor with Paul, who also plays a major role in the book; and 2) permanently compromising her mental health. Surprisingly, given his tepid Protestant upbringing, Ramsay becomes a historian of Christian saints, and comes to consider Mrs. Dempster part of his personal pantheon for a few incidents he thinks of as miracles – not least his survival during First World War service. And this is despite Mrs. Dempster being caught in a situation that seriously compromises her standing in Deptford.

Specifically, he dodged a snowball meant for him – thrown by his frenemy, Percy Boyd Staunton – and it hit Mrs. Dempster, wife of the local Baptist minister, in the back of the head, knocking her over and 1) sending her into early labor with Paul, who also plays a major role in the book; and 2) permanently compromising her mental health. Surprisingly, given his tepid Protestant upbringing, Ramsay becomes a historian of Christian saints, and comes to consider Mrs. Dempster part of his personal pantheon for a few incidents he thinks of as miracles – not least his survival during First World War service. And this is despite Mrs. Dempster being caught in a situation that seriously compromises her standing in Deptford.

The novel is presented as a long, confessional letter Ramsay writes, on the occasion of his retirement, to the headmaster of the boys’ school where he taught history for 45 years. Staunton, later known simply as “Boy,” becomes a sugar magnate and politician; Paul becomes a world-renowned illusionist known by various stage names. Both Paul and Ramsay are obsessed with the unexplained and impossible, but where Paul manipulates appearances and fictionalizes the past, Ramsay looks for miracles. The Fool, the Saint and the Devil are generic characters we’re invited to ponder; perhaps they also have incarnations in the novel?

Fifth Business ends with a mysterious death, and though there are clues that seem to point to whodunit, the fact that the story segues straight into a second volume, with a third to come, indicates that it’s all more complicated than it might seem. I was so intrigued that, thanks to my omnibus edition, I carried right on with the first chapter of The Manticore (1972), which is also in the first person but this time narrated by Staunton’s son, David, from Switzerland. Freudian versus Jungian psychology promises to be a major dichotomy in this one, and I’m sure that the themes of the complexity of human desire, the search for truth and goodness, and the difficulty of seeing oneself and others clearly will crop up once again.

This was a very rewarding reading experience. I’d recommend Davies to those who enjoy novels of ideas, such as Iris Murdoch’s. I’ll carry on with at least the second volume of the trilogy for now, and I’ve also acquired the first volume of another, later trilogy to try.

My rating:

Some favorite lines:

“I cannot remember a time when I did not take it as understood that everybody has at least two, if not twenty-two, sides to him.”

“Forgive yourself for being a human creature, Ramezay. That is the beginning of wisdom; that is part of what is meant by the fear of God; and for you it is the only way to save your sanity.”

It’s also fascinating to see the contrast between how Ramsay sees himself, and how others do:

“it has been my luck to appear more literate than I really am, owing to a cadaverous and scowling cast of countenance, and a rather pedantic Scots voice”

vs.

“Good God, don’t you think the way you rootle in your ear with your little finger delights the boys? And the way you waggle your eyebrows … and those horrible Harris tweed suits you wear … And that disgusting trick of blowing your nose and looking into your handkerchief as if you expected to prophesy something from the mess. You look ten years older than your age.”

Book Serendipity Incidents of 2019 (So Far)

I’ve continued to post my occasional reading coincidences on Twitter and/or Instagram. This is when two or more books that I’m reading at the same time or in quick succession have something pretty bizarre in common. Because I have so many books on the go at once – usually between 10 and 20 – I guess I’m more prone to such serendipitous incidents. (The following are in rough chronological order.)

What’s the weirdest coincidence you’ve had lately?

- Two titles that sound dubious about miracles: There Will Be No Miracles Here by Casey Gerald and The Unwinding of the Miracle: A Memoir of Life, Death, and Everything that Comes After by Julie Yip-Williams

- Two titles featuring light: A Light Song of Light by Kei Miller and The Age of Light by Whitney Scharer

- Grey Poupon mustard (and its snooty associations, as captured in the TV commercials) mentioned in There Will Be No Miracles Here by Casey Gerald and Drinking: A Love Story by Caroline Knapp

“I Wanna Dance with Somebody” (the Whitney Houston song) referenced in There Will Be No Miracles Here by Casey Gerald and Don’t Call Us Dead by Danez Smith

“I Wanna Dance with Somebody” (the Whitney Houston song) referenced in There Will Be No Miracles Here by Casey Gerald and Don’t Call Us Dead by Danez Smith

- Two books have an on/off boyfriend named Julian: Drinking: A Love Story by Caroline Knapp and Extinctions by Josephine Wilson

- There’s an Aunt Marjorie in When I Had a Little Sister by Catherine Simpson and Extinctions by Josephine Wilson

- Set (at least partially) in a Swiss chalet: This Sunrise of Wonder by Michael Mayne and Crazy for God by Frank Schaeffer

- A character named Kiki in The Sacred and Profane Love Machine by Iris Murdoch, The Age of Light by Whitney Scharer, AND Improvement by Joan Silber

Two books set (at least partially) in mental hospitals: Mind on Fire by Arnold Thomas Fanning and Faces in the Water by Janet Frame

Two books set (at least partially) in mental hospitals: Mind on Fire by Arnold Thomas Fanning and Faces in the Water by Janet Frame

- Two books in which a character thinks the saying is “It’s a doggy dog world” (rather than “dog-eat-dog”): The Friend by Sigrid Nunez and The Octopus Museum by Brenda Shaughnessy

- Reading a novel about Lee Miller (The Age of Light by Whitney Scharer), I find a metaphor involving her in My Year of Rest and Relaxation by Ottessa Moshfegh: (the narrator describes her mother) “I think she got away with so much because she was beautiful. She looked like Lee Miller if Lee Miller had been a bedroom drunk.” THEN I come across a poem in Clive James’s Injury Time entitled “Lee Miller in Hitler’s Bathtub”

- On the same night that I started Siri Hustvedt’s new novel, Memories of the Future, I also started a novel that had a Siri Hustvedt quote (from The Blindfold) as the epigraph: Besotted by Melissa Duclos

- In two books “elicit” was printed where the author meant “illicit” – I’m not going to name and shame, but one of these instances was in a finished copy! (the other in a proof, which is understandable)

- Three books in which the bibliography is in alphabetical order BY BOOK TITLE! Tell me this is not a thing; it will not do! (Vagina: A Re-education by Lynn Enright; Let’s Talk about Death (over Dinner) by Michael Hebb; Telling the Story: How to Write and Sell Narrative Nonfiction by Peter Rubie)

References to Gerard Manley Hopkins in Another King, Another Country by Richard Holloway, This Sunrise of Wonder by Michael Mayne and The Point of Poetry by Joe Nutt (these last two also discuss his concept of the “inscape”)

References to Gerard Manley Hopkins in Another King, Another Country by Richard Holloway, This Sunrise of Wonder by Michael Mayne and The Point of Poetry by Joe Nutt (these last two also discuss his concept of the “inscape”)

- Creative placement of words on the page (different fonts; different type sizes, capitals, bold, etc.; looping around the page or at least not in traditional paragraphs) in When Death Takes Something from You Give It Back by Naja Marie Aidt [not pictured below], How Proust Can Change Your Life by Alain de Botton, Stubborn Archivist by Yara Rodrigues Fowler, Alice Iris Red Horse: Selected Poems of Yoshimasu Gozo and Lanny by Max Porter

- Twin brothers fall out over a girl in Cutting for Stone by Abraham Verghese and one story from the upcoming book Meteorites by Julie Paul

- Characters are described as being “away with the fairies” in Lanny by Max Porter and Away by Jane Urquhart

Schindler’s Ark/List is mentioned in In the Beginning: A New Reading of the Book of Genesis by Karen Armstrong and Telling the Story: How to Write and Sell Narrative Nonfiction by Peter Rubie … makes me think that I should finally pick up my copy!

Schindler’s Ark/List is mentioned in In the Beginning: A New Reading of the Book of Genesis by Karen Armstrong and Telling the Story: How to Write and Sell Narrative Nonfiction by Peter Rubie … makes me think that I should finally pick up my copy!

The Three Best Books I’ve Read So Far This Year

I’m very stingy with my 5-star ratings, so when I give one out you can be assured that a book is truly special. These three are all backlist reads – look out for my Classic of the Month post next week for a fourth that merits 5 stars – that are well worth seeking out. Out of the 50 books I’ve read so far this year, these are far and away the best.

This Sunrise of Wonder: Letters for the Journey by Michael Mayne (1995)

The cover image is Mark Rothko’s Orange, Red, Yellow (1956).

I plucked this Wigtown purchase at random from my shelves and it ended up being just what I needed to lift me out of January’s funk. Mayne’s thesis is that experiencing wonder, “rare, life-changing moments of seeing or hearing things with heightened perception,” is what makes us human. Call it an epiphany (as Joyce did), call it a moment of vision (as Woolf did), call it a feeling of communion with the universe; whatever you call it, you know what he is talking about. It’s that fleeting sense that you are right where you should be, that you have tapped into some universal secret of how to be in the world.

Mayne believes poets, musicians and painters, in particular, reawaken us to wonder by encouraging us to pay close attention. His frame of reference is wide, with lots of quotations and poetry extracts; he has a special love for Turner, Monet and Van Gogh and for Rilke, Blake and Hopkins. Mayne was an Anglican priest and Dean of Westminster, so he comes at things from a Christian perspective, but most of his advice is generically spiritual and not limited to a particular religion. There are about 50 pages towards the end that are specifically about Jesus; one could skip those if desired.

The book is a series of letters written to his grandchildren from a chalet in the Swiss Alps one May to June. Especially with the frequent quotations and epigraphs, the effect is of a rich compendium of wisdom from the ages. I don’t often feel awake to life’s wonder – I get lost in its tedium and unfairness instead – but this book gave me something to aspire to.

A few of the many wonderful quotes:

“The mystery is that the created world exists. It is: I am. The mystery is life itself, together with the fact that however much we seek to explore and to penetrate them, the impenetrable shadows remain.”

“Once wonder goes; once mystery is dismissed; once the holy and the numinous count for nothing; then human life becomes cheap and it is possible with a single bullet to shatter that most miraculous thing, a human skull, with scarcely a second thought. Wonder and compassion go hand-in-hand.”

“this recognition of my true worth is something entirely different from selfishness, that turned-in-upon-myselfness of the egocentric. … It is a kind of blasphemy to view ourselves with so little compassion when God views us with so much.”

Body of Work: Meditations on Mortality from the Human Anatomy Lab by Christine Montross (2007)

When she was training to become a doctor in Rhode Island, Montross and her anatomy lab classmates were assigned an older female cadaver they named Eve. Eve taught her everything she knows about the human body. Montross is also a published poet, as evident in her lyrical exploration of the attraction and strangeness of working with the remnants of someone who was once alive. She sees the contrasts, the danger, the theatre, the wonder of it all:

When she was training to become a doctor in Rhode Island, Montross and her anatomy lab classmates were assigned an older female cadaver they named Eve. Eve taught her everything she knows about the human body. Montross is also a published poet, as evident in her lyrical exploration of the attraction and strangeness of working with the remnants of someone who was once alive. She sees the contrasts, the danger, the theatre, the wonder of it all:

“Stacked beside me on my sage green couch: this spinal column that wraps into a coil without muscle to hold it upright, hands and feet tied together with floss, this skull hinged and empty. A man’s teeth.”

“When I look at the tissues and organs responsible for keeping me alive, I am not reassured. The wall of the atrium is the thickness of an old T-shirt, and yet a tear in it means instant death. The aorta is something I have never thought about before, but if mine were punctured, I would exsanguinate, a deceptively beautiful word”

All through her training, Montross has to remind herself to preserve her empathy despite a junior doctor’s fatigue and the brutality of the work (“The force necessary in the dissections feels barbarous”), especially as the personal intrudes on her career through her grandparents’ decline and her plans to start a family with her wife – which I gather is more of a theme in her next book, Falling into the Fire, about her work as a psychiatrist. I get through a whole lot of medical reads, as any of my regular readers will know, but this one is an absolute stand-out for its lyrical language, clarity of vision, honesty and compassion.

There There by Tommy Orange (2018)

Had I finished this late last year instead of in the second week of January, it would have been vying with Lauren Groff’s Florida for the #1 spot on my Best Fiction of 2018 list.

The title – presumably inspired by both Gertrude Stein’s remark about Oakland, California (“There is no there there”) and the Radiohead song – is no soft pat of reassurance. It’s falsely lulling; if anything, it’s a warning that there is no consolation to be found here. Orange’s dozen main characters are urban Native Americans converging on the annual Oakland Powwow. Their lives have been difficult, to say the least, with alcoholism, teen pregnancy, and gang violence as recurring sources of trauma. They have ongoing struggles with grief, mental illness and the far-reaching effects of fetal alcohol syndrome.

The title – presumably inspired by both Gertrude Stein’s remark about Oakland, California (“There is no there there”) and the Radiohead song – is no soft pat of reassurance. It’s falsely lulling; if anything, it’s a warning that there is no consolation to be found here. Orange’s dozen main characters are urban Native Americans converging on the annual Oakland Powwow. Their lives have been difficult, to say the least, with alcoholism, teen pregnancy, and gang violence as recurring sources of trauma. They have ongoing struggles with grief, mental illness and the far-reaching effects of fetal alcohol syndrome.

The novel cycles through most of the characters multiple times, alternating between the first and third person (plus one second person chapter). As we see them preparing for the powwow, whether to dance and drum, meet estranged relatives, or get up to no good, we start to work out the links between everyone. I especially liked how Orange unobtrusively weaves in examples of modern technology like 3D printing and drones.

The writing in the action sequences is noticeably weaker, and I wasn’t fully convinced by the sentimentality-within-tragedy of the ending, but I was awfully impressed with this novel overall. I’d recommend it to readers of David Chariandy’s Brother and especially Sunil Yapa’s Your Heart Is a Muscle the Size of a Fist. It was my vote for the National Book Critics Circle’s John Leonard Prize (for the best first book, of any genre, published in 2018), and I was pleased that it went on to win.

No Place to Lay One’s Head by Françoise Frenkel (1945)

Fittingly, I finished reading this on Sunday, which was International Holocaust Remembrance Day. Even after seven decades, we’re still unearthing new Holocaust narratives, such as this one: rediscovered in a flea market in 2010, it was republished in French in 2015 and first became available in English translation in 2017.

Born Frymeta Idesa Frenkel in Poland, the author (1889–1975) was a Jew who opened the first French-language bookstore in Berlin in 1921. After Kristallnacht and the seizure of her stock and furniture, she left for France and a succession of makeshift situations, mostly in Avignon and Nice. She lived in a hotel, a chateau, and the spare room of a sewing machinist whose four cats generously shared their fleas. All along, the Mariuses, a pair of hairdressers, were like guardian angels she could go back to between emergency placements.

Born Frymeta Idesa Frenkel in Poland, the author (1889–1975) was a Jew who opened the first French-language bookstore in Berlin in 1921. After Kristallnacht and the seizure of her stock and furniture, she left for France and a succession of makeshift situations, mostly in Avignon and Nice. She lived in a hotel, a chateau, and the spare room of a sewing machinist whose four cats generously shared their fleas. All along, the Mariuses, a pair of hairdressers, were like guardian angels she could go back to between emergency placements.

This memoir showcases the familiar continuum of uneasiness blooming into downright horror as people realized what was going on in Europe. To start with one could downplay the inconveniences of having belongings confiscated and work permits denied, of squeezing onto packed trains and being turned back at closed borders. Only gradually, as rumors spread of what was happening to deported Jews, did Frenkel understand how much danger she was in.

The second half of the book is more exciting than the first, especially after Frenkel is arrested at the Swiss border. (Even though you know she makes it out alive.) Her pen portraits of her fellow detainees show real empathy as well as writing talent. Strangely, Frenkel never mentions her husband, who went into exile in France in 1933 and died in Auschwitz in 1942. I would also have liked to hear more about her 17 years of normal bookselling life before everything kicked off. Still, this is a valuable glimpse into the events of the time, and a comparable read to Władysław Szpilman’s The Pianist.

My rating:

No Place to Lay One’s Head (translated from the French by Stephanie Smee) is issued in paperback today, January 31st, by Pushkin Press. This edition includes a preface by Patrick Modiano and a dossier of documents and photos relating to Frenkel’s life. My thanks to the publisher for the free copy for review.

If only I’d realized this was set on a train to Berlin, I could have read it in the same situation! Instead, it was a random find while shelving in the children’s section of the library. Emil sets out on a slow train from Neustadt to stay with his aunt, grandmother and cousin in Berlin for a week’s holiday. His mother gives him £7 in an envelope he pins inside his coat for safekeeping. There are four adults in the carriage with him, but three get off early, leaving Emil alone with a man in a bowler hat. Much as he strives to stay awake, Emil drops off. No sooner has the train pulled into Berlin than he realizes the envelope is gone along with his fellow traveller. “There were four million people in Berlin at that moment, and not one of them cared what was happening to Emil Tischbein.” He’s sure he’ll have to chase the man in the bowler hat all by himself, but instead he enlists the help of a whole gang of boys, including Gustav who carries a motor-horn and poses as a bellhop, Professor with the glasses, and Little Tuesday who mans the phone lines. Together they get justice for Emil, deliver a wanted criminal to the police, and earn a hefty reward. This was a cute story and it was refreshing for children’s word to be taken seriously. There’s also the in-joke of the journalist who interviews Emil being Kästner. I’m sure as a kid I would have found this a thrilling adventure, but the cynical me of today deemed it unrealistic. (Public library) [153 pages]

If only I’d realized this was set on a train to Berlin, I could have read it in the same situation! Instead, it was a random find while shelving in the children’s section of the library. Emil sets out on a slow train from Neustadt to stay with his aunt, grandmother and cousin in Berlin for a week’s holiday. His mother gives him £7 in an envelope he pins inside his coat for safekeeping. There are four adults in the carriage with him, but three get off early, leaving Emil alone with a man in a bowler hat. Much as he strives to stay awake, Emil drops off. No sooner has the train pulled into Berlin than he realizes the envelope is gone along with his fellow traveller. “There were four million people in Berlin at that moment, and not one of them cared what was happening to Emil Tischbein.” He’s sure he’ll have to chase the man in the bowler hat all by himself, but instead he enlists the help of a whole gang of boys, including Gustav who carries a motor-horn and poses as a bellhop, Professor with the glasses, and Little Tuesday who mans the phone lines. Together they get justice for Emil, deliver a wanted criminal to the police, and earn a hefty reward. This was a cute story and it was refreshing for children’s word to be taken seriously. There’s also the in-joke of the journalist who interviews Emil being Kästner. I’m sure as a kid I would have found this a thrilling adventure, but the cynical me of today deemed it unrealistic. (Public library) [153 pages] I’ve been equally enchanted by Kehlmann’s historical fiction (

I’ve been equally enchanted by Kehlmann’s historical fiction ( This was longlisted for the International Booker Prize and is the current Waterstones book of the month. The Swiss author’s seventh novel appears to be autofiction: the protagonist is named Christian Kracht and there are references to his previous works. Whether he actually went on a profligate road trip with his 80-year-old mother, who could say. I tend to think some details might be drawn from life – her physical and mental health struggles, her father’s Nazism, his father’s weird collections and sexual predilections – but brewed into a madcap maelstrom of a plot that sees the pair literally throwing away thousands of francs. Her fortune was gained through arms industry investment and she wants rid of it, so they hire private taxis and planes. If his mother has a whim to pick some edelweiss, off they go to find it. All the while she swigs vodka and swallows pills, and Christian changes her colostomy bags. I was wowed by individual lines (“This was the katabasis: the decline of the family expressed in the topography of her face”; “everything that does not rise into consciousness will return as fate”; “the glacial sun shone from above, unceasing and relentless, upon our little tableau vivant”) but was left chilly overall by the satire on the ultra-wealthy and those who seek to airbrush history. The fun connections: Like the Kehlmann, this involves arbitrary travel and happens to end in Africa. More than once, Kracht is confused for Kehlmann. (Little Free Library) [190 pages]

This was longlisted for the International Booker Prize and is the current Waterstones book of the month. The Swiss author’s seventh novel appears to be autofiction: the protagonist is named Christian Kracht and there are references to his previous works. Whether he actually went on a profligate road trip with his 80-year-old mother, who could say. I tend to think some details might be drawn from life – her physical and mental health struggles, her father’s Nazism, his father’s weird collections and sexual predilections – but brewed into a madcap maelstrom of a plot that sees the pair literally throwing away thousands of francs. Her fortune was gained through arms industry investment and she wants rid of it, so they hire private taxis and planes. If his mother has a whim to pick some edelweiss, off they go to find it. All the while she swigs vodka and swallows pills, and Christian changes her colostomy bags. I was wowed by individual lines (“This was the katabasis: the decline of the family expressed in the topography of her face”; “everything that does not rise into consciousness will return as fate”; “the glacial sun shone from above, unceasing and relentless, upon our little tableau vivant”) but was left chilly overall by the satire on the ultra-wealthy and those who seek to airbrush history. The fun connections: Like the Kehlmann, this involves arbitrary travel and happens to end in Africa. More than once, Kracht is confused for Kehlmann. (Little Free Library) [190 pages]

Some of you may know Lory, who is training as a spiritual director, from her blog,

Some of you may know Lory, who is training as a spiritual director, from her blog,

These 17 flash fiction stories fully embrace the possibilities of magic and weirdness, particularly to help us reconnect with the dead. Brad and I are literary acquaintances from our time working on (the now defunct) Bookkaholic web magazine in 2014–15. I liked this even more than his first book,

These 17 flash fiction stories fully embrace the possibilities of magic and weirdness, particularly to help us reconnect with the dead. Brad and I are literary acquaintances from our time working on (the now defunct) Bookkaholic web magazine in 2014–15. I liked this even more than his first book,  I had a misconception that each chapter would be written by a different author. I think that would actually have been the more interesting approach. Instead, each character is voiced by a different author, and sometimes by multiple authors across the 14 chapters (one per day) – a total of 36 authors took part. I soon wearied of the guess-who game. I most enjoyed the frame story, which was the work of Douglas Preston, a thriller author I don’t otherwise know.

I had a misconception that each chapter would be written by a different author. I think that would actually have been the more interesting approach. Instead, each character is voiced by a different author, and sometimes by multiple authors across the 14 chapters (one per day) – a total of 36 authors took part. I soon wearied of the guess-who game. I most enjoyed the frame story, which was the work of Douglas Preston, a thriller author I don’t otherwise know.

This was only the second time I’ve read one of Jansson’s books aimed at adults (as opposed to five from the Moomins series). Whereas A Winter Book didn’t stand out to me when I read it in 2012 – though I will try it again this winter, having acquired a free copy from a neighbour – this was a lovely read, so evocative of childhood and of languid summers free from obligation. For two months, Sophia and Grandmother go for mini adventures on their tiny Finnish island. Each chapter is almost like a stand-alone story in a linked collection. They make believe and welcome visitors and weather storms and poke their noses into a new neighbour’s unwanted construction.

This was only the second time I’ve read one of Jansson’s books aimed at adults (as opposed to five from the Moomins series). Whereas A Winter Book didn’t stand out to me when I read it in 2012 – though I will try it again this winter, having acquired a free copy from a neighbour – this was a lovely read, so evocative of childhood and of languid summers free from obligation. For two months, Sophia and Grandmother go for mini adventures on their tiny Finnish island. Each chapter is almost like a stand-alone story in a linked collection. They make believe and welcome visitors and weather storms and poke their noses into a new neighbour’s unwanted construction. In a hypnotic monologue, a woman tells of her time with a violent partner (the man before, or “Manfore”) who thinks her reaction to him is disproportionate and all due to the fact that she has never processed being raped two decades ago. When she goes in for a routine breast scan, she shows the doctor her bruised arm, wanting there to be a definitive record of what she’s gone through. It’s a bracing echo of the moment she walked into a police station to report the sexual assault (and oh but the questions the male inspector asked her are horrible).

In a hypnotic monologue, a woman tells of her time with a violent partner (the man before, or “Manfore”) who thinks her reaction to him is disproportionate and all due to the fact that she has never processed being raped two decades ago. When she goes in for a routine breast scan, she shows the doctor her bruised arm, wanting there to be a definitive record of what she’s gone through. It’s a bracing echo of the moment she walked into a police station to report the sexual assault (and oh but the questions the male inspector asked her are horrible). In the early 1880s, Mikhail Alexandrovich Kovrov, assistant director of St. Petersburg Zoo, is brought the hide and skull of an ancient horse species assumed extinct. Although a timorous man who still lives with his mother, he becomes part of an expedition to Mongolia to bring back live specimens. In 1992, Karin, who has been obsessed with Przewalski’s horses since encountering them as a child in Nazi Germany, spearheads a mission to return the takhi to Mongolia and set up a breeding population. With her is her son Matthias, tentatively sober after years of drug abuse. In 2064 Norway, Eva and her daughter Isa are caretakers of a decaying wildlife park that houses a couple of wild horses. When a climate migrant comes to stay with them and the electricity goes off once and for all, they have to decide what comes next. This future story line engaged me the most.

In the early 1880s, Mikhail Alexandrovich Kovrov, assistant director of St. Petersburg Zoo, is brought the hide and skull of an ancient horse species assumed extinct. Although a timorous man who still lives with his mother, he becomes part of an expedition to Mongolia to bring back live specimens. In 1992, Karin, who has been obsessed with Przewalski’s horses since encountering them as a child in Nazi Germany, spearheads a mission to return the takhi to Mongolia and set up a breeding population. With her is her son Matthias, tentatively sober after years of drug abuse. In 2064 Norway, Eva and her daughter Isa are caretakers of a decaying wildlife park that houses a couple of wild horses. When a climate migrant comes to stay with them and the electricity goes off once and for all, they have to decide what comes next. This future story line engaged me the most. Vogt’s Swiss-set second novel is about a tight-knit matriarchal family whose threads have started to unravel. For Rahel, motherhood has taken her away from her vocation as a singer. Boris stepped up when she was pregnant with another man’s baby and has been as much of a father to Rico as to Leni, the daughter they had together afterwards. But now Rahel’s postnatal depression is stopping her from bonding with the new baby, and she isn’t sure this quartet is going to make it in the long term.

Vogt’s Swiss-set second novel is about a tight-knit matriarchal family whose threads have started to unravel. For Rahel, motherhood has taken her away from her vocation as a singer. Boris stepped up when she was pregnant with another man’s baby and has been as much of a father to Rico as to Leni, the daughter they had together afterwards. But now Rahel’s postnatal depression is stopping her from bonding with the new baby, and she isn’t sure this quartet is going to make it in the long term.

A mudslide blocked the route we should have taken back from Milan to Paris, so we rebooked onto trains via Switzerland. This plus the sub-Alpine setting for our next-to-last day made the perfect context for racing through Where the Hornbeam Grows: A Journey in Search of a Garden by Beth Lynch in just two days. Lynch moved from England to Switzerland when her husband took a job in Zurich. Suddenly she had to navigate daily life, including frosty locals and convoluted bureaucracy, in a second language. The sense of displacement was exacerbated by her lack of access to a garden. Gardening had always been a whole-family passion, and after her parents’ death their Sussex garden was lost to her. Two years later she and her husband moved to a cottage in western Switzerland and cultivated a garden idyll, but it wasn’t enough to neutralize their loneliness.

A mudslide blocked the route we should have taken back from Milan to Paris, so we rebooked onto trains via Switzerland. This plus the sub-Alpine setting for our next-to-last day made the perfect context for racing through Where the Hornbeam Grows: A Journey in Search of a Garden by Beth Lynch in just two days. Lynch moved from England to Switzerland when her husband took a job in Zurich. Suddenly she had to navigate daily life, including frosty locals and convoluted bureaucracy, in a second language. The sense of displacement was exacerbated by her lack of access to a garden. Gardening had always been a whole-family passion, and after her parents’ death their Sussex garden was lost to her. Two years later she and her husband moved to a cottage in western Switzerland and cultivated a garden idyll, but it wasn’t enough to neutralize their loneliness. Confessions of a Bookseller by Shaun Bythell: This picks up right where The Diary of a Bookseller left off and carries through the whole of 2015. Again it’s built on the daily routines of buying and selling books, including customers’ and colleagues’ quirks, and of being out and about in a small town. I wished I was in Wigtown instead of Milan! Because of where I was reading the book, I got particular enjoyment out of the characterization of Emanuela (soon known as “Granny” for her poor eyesight and myriad aches and gripes), who comes over from Italy to volunteer in the bookshop for the summer. Bythell’s break-up with “Anna” is a recurring theme in this volume, I suspect because his editor/publisher insisted on an injection of emotional drama.

Confessions of a Bookseller by Shaun Bythell: This picks up right where The Diary of a Bookseller left off and carries through the whole of 2015. Again it’s built on the daily routines of buying and selling books, including customers’ and colleagues’ quirks, and of being out and about in a small town. I wished I was in Wigtown instead of Milan! Because of where I was reading the book, I got particular enjoyment out of the characterization of Emanuela (soon known as “Granny” for her poor eyesight and myriad aches and gripes), who comes over from Italy to volunteer in the bookshop for the summer. Bythell’s break-up with “Anna” is a recurring theme in this volume, I suspect because his editor/publisher insisted on an injection of emotional drama.

City of Girls by Elizabeth Gilbert: There’s a fun, saucy feel to this novel set mostly in 1940s New York City. Twenty-year-old Vivian Morris comes to sew costumes for her Aunt Peg’s rundown theatre and falls in with a disreputable lot of actors and showgirls. When she does something bad enough to get her in the tabloids and jeopardize her future, she retreats in disgrace to her parents’ – but soon the war starts and she’s called back to help with Peg’s lunchtime propaganda shows at the Brooklyn Navy Yard. The quirky coming-of-age narrative reminded me a lot of classic John Irving, while the specifics of the setting made me think of Wise Children, All the Beautiful Girls

City of Girls by Elizabeth Gilbert: There’s a fun, saucy feel to this novel set mostly in 1940s New York City. Twenty-year-old Vivian Morris comes to sew costumes for her Aunt Peg’s rundown theatre and falls in with a disreputable lot of actors and showgirls. When she does something bad enough to get her in the tabloids and jeopardize her future, she retreats in disgrace to her parents’ – but soon the war starts and she’s called back to help with Peg’s lunchtime propaganda shows at the Brooklyn Navy Yard. The quirky coming-of-age narrative reminded me a lot of classic John Irving, while the specifics of the setting made me think of Wise Children, All the Beautiful Girls Judgment Day by Sandra M. Gilbert: English majors will know Gilbert best for her landmark work of criticism, The Madwoman in the Attic (co-written with Susan Gubar). I had no idea that she writes poetry. This latest collection has a lot of interesting reflections on religion, food and art, as well as elegies to those she’s lost. Raised Catholic, Gilbert married a Jew, and the traditions of Judaism still hold meaning for her after husband’s death even though she’s effectively an atheist. “Pompeii and After,” a series of poems describing food scenes in paintings, from da Vinci to Hopper, is particularly memorable.

Judgment Day by Sandra M. Gilbert: English majors will know Gilbert best for her landmark work of criticism, The Madwoman in the Attic (co-written with Susan Gubar). I had no idea that she writes poetry. This latest collection has a lot of interesting reflections on religion, food and art, as well as elegies to those she’s lost. Raised Catholic, Gilbert married a Jew, and the traditions of Judaism still hold meaning for her after husband’s death even though she’s effectively an atheist. “Pompeii and After,” a series of poems describing food scenes in paintings, from da Vinci to Hopper, is particularly memorable.  Vintage 1954 by Antoine Laurain: Dreadful! I would say: avoid this sappy time-travel novel at all costs. I thought the setup promised a gentle dose of fantasy, and liked the fact that the characters could meet their ancestors and Paris celebrities during their temporary stay in 1954. But the characters are one-dimensional stereotypes, and the plot is far-fetched and silly. I know many others have found this delightful, so consider me in the minority…

Vintage 1954 by Antoine Laurain: Dreadful! I would say: avoid this sappy time-travel novel at all costs. I thought the setup promised a gentle dose of fantasy, and liked the fact that the characters could meet their ancestors and Paris celebrities during their temporary stay in 1954. But the characters are one-dimensional stereotypes, and the plot is far-fetched and silly. I know many others have found this delightful, so consider me in the minority…